Editors’ note: This article is featured in NPQ‘s blockbuster summer 2013 edition: “New Gatekeepers of Philanthropy.”

The Nonprofit Quarterly is going to press with this issue on the changing landscape of philanthropy immediately after the 2013 Giving USA report was released. The report confirms that the much-touted recovery from the recession that began in 2008 is only very slowly being felt in charitable giving. Putting this in perspective, in 2008, philanthropy was at its highest level ever, but the dive it took was precipitous, at about 15 percent in 2008 and 2009 combined—adjusted for inflation—and the climb back up may be so steep as to slow us nearly to a crawl.1

In short form, this is the slowest post-recession recovery of a giving level in recorded history. Losses felt in previous recessions have been regained within three years; we are already at four years and counting, and the really bad news is that the rate of growth appears to be slowing significantly. Most of the recovery in giving happened in 2010, when giving increased by 5 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars. In 2011, the increase was 1.25 percent, and in 2012 it was estimated at 1 percent. At this rate, the recovery in charitable giving is likely destined to take at least twice what it has taken after previous recessions—approximately six to seven years—and that is, perhaps, being optimistic.

But what should be just as important to fundraisers is the fact that philanthropy is not only coming back slowly but in different form. Some of the differences are hard to pin down because the targets are moving and there is a lack of readily available research that asks the right questions, but we feel fairly certain that there are serious shifts afoot.

As NPQ prepared to take on a mapping of changes in the philanthropic landscape, it recognized that this would be informed not only by changes that have occurred but also by the trajectories of that change. In other words, some trends are occurring quickly, almost like a tumble downhill, and others may remind us more of Sisyphus painstakingly pushing a rock up the side of a mountain.

Many of the more massive shifts in philanthropy that have occurred over the last twenty years might be grouped under the rubric “disintermediation” (the elimination of an intermediary), and the major force in charitable disintermediation is primarily, but not solely, the Internet.

Examples of Intermediaries

Examples of intermediaries in giving are the federated campaigns such as the United Way affiliates and community foundation general funds. These relatively recent examples of funding intermediaries would previously have acted as proxies for givers—receiving gifts and often making decisions on the donor’s behalf out of a general fund. They were there to facilitate and direct giving, but more recently we see that those who may previously have given to a combined fund are making their gifts more directly, parking their gifts in some cases in charitable gift funds. This is a trend that began more than twenty years ago, as community foundations saw the numbers of their donor-advised funds growing and United Ways began to see an ever-greater proportion of gifts given as donor directed to a specific agency. Of course, donor-advised funds (DAFs) are still an intermediary of some kind, but although they are held or overseen by a foundation or charitable gift fund, grantmaking decisions are made by the donors.

The Internet facilitates direct giving by providing easy access to information about charities and ways to give online. Institutions such as GuideStar were developed to ensure that certain data were broadly available, and charities have become increasingly acclimated to the fact that their websites must be considered a major interchange between themselves and their publics. This may be eroding the traditional base of federated giving programs, and a series of interconnected effects will be felt by nonprofits.

Taking just one example, according to Giving USA, giving to so-called public benefit organizations was up, but within that category—which includes intermediaries like the United Way and the Combined Federal Campaign—are also a growing number of donor-advised funds handling an increasing number of philanthropic assets.

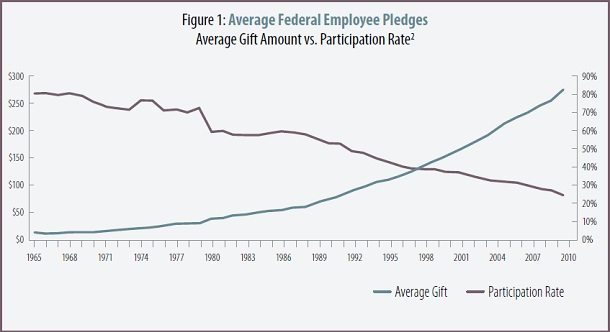

While we do not have the figures for the United Ways, the Combined Federal Campaign has been in a pretty steady decline since 2005, when it brought in $259.7 million; this year in inflation-adjusted dollars it brought in only $212.5 million. Additionally, there is a long-term trend toward far lower participation, which is to some extent obscured by larger gift sizes (see figure 1).

Because of the phenomenal growth of at least the largest of the commercial funds over the past year, and due to the fact that the payout at those funds is only an estimated 14 percent annually, we can assume that there is less moving through this field to nonprofits, which could actually use that money. Concurrently, since giving to foundations is down, we might suspect that people who may have previously given to foundations are now just placing their money in the DAFs—and that may be a good thing. Many foundations observe the 5 percent payout floor as a ceiling, but it appears to us that there must be no growth or negative growth in federated workplace campaigns, which pay out largely within the same year that money is raised.

Of course, another category of intermediaries is the welter of philanthropic and wealth advisors who help people of means figure out how to invest their assets in charities, whether direct donations, DAFs, or, if they have the wherewithal, their own foundations—or sometimes a combination of all of the above. To some extent, the disintermediation dynamic has impacted advisors themselves, as donors are reluctant to pay too high a premium for information that they can get at much lower cost from GuideStar or DAF managers.

Disintermediation Does Not Necessarily Mean Individualism

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As tools and practices have changed, so have the expectations and habits in the big mix of individual givers. For some, the act of contributing is bound up with a collective act they are more intimately a part of. A good example of this was the crowdfunding effort to place an ad in the New York Times explaining the protests in Turkey. Not only did people give to a common cause, but they voted on the ad, too, choosing from a number of proposals. And, further, they will be voting on what to do with money that exceeded the need. These small and sometimes larger hubs of engagement and giving exemplify the times; they are at the very least the temporary embodiments of communities of purpose.

And what about that transience? Our worlds have expanded through use of the Internet such that we can establish dynamic communities of purpose with people who are far-flung geographically. This creates a challenge for nonprofits to compete in terms of attracting and keeping the attention of those drawn to their work. Retention becomes more difficult—loyalty must be earned and preserved.

In a way, this is a return to form. We have always known that there is a connection between volunteering and giving, but in these situations the two are inextricably linked. Will this closeness of action and investment become more the norm?

In some cases, crowdfunding is even allowing people to bypass nonprofits altogether to help the individual. A recent article in the Washington Post highlighted the growing practice of people raising money over the Internet to defray personal medical costs. It opens with the story of one man with lung cancer who has decent insurance coverage, but, as co-payments and out-of-pocket costs mounted, the family turned to the Internet and their own network to eventually raise $56,800 from 325 friends and family members. The donations to his fund ranged from $10 to $2,000.

The above campaign was run on the site GiveForward, a for-profit that charged 7 percent for its services. GiveForward raised $225,000 for 359 campaigns in 2008, the year that it was launched, and as of this year it has grown to 15,000 campaigns raising $20 million. Other such sites include GoFundMe.com, YouCaring.com, FundRazr.com, and Indiegogo.com, raising money not just for medical costs but also for tuition, travel, disaster relief, pets’ medical care, and funeral costs. Very often, those donating to such causes are family and friends of those needing help, but in the case of disaster relief we have seen the rise of such specific crowdfunded efforts as The One Fund Boston, an entity organized and seeded overnight, where corporate and individual gifts mixed to recompense victims of the Boston Marathon bombing for their injuries. Efforts like these have evolved quickly over the past few years, with lessons learned along the way.

These types of campaigns are interesting on any number of levels. Other crowdfunded efforts were organized alongside The One Fund Boston, including a campaign to replace the bullet-ridden boat in which one of the Boston Marathon bombers was captured. The proceeds of this were rejected by the boat owner because he did not think, in light of the losses experienced by others, that his boat was a priority. In a way, then, rather than being super-organized, these somewhat informal expressions of collective giving are perhaps more eloquent and might tell us something about the ways people are feeling and responding to the world around them.

Crowdfunding in philanthropy does not, of course, stand completely apart from crowdfunding of business endeavors, a trend that has taken hold quickly. We will see what its evolution brings.

Anti-Democratic Philanthropy—So What Is New?

But there is certainly a continuum still at play. Some elements of philanthropy are immune to any democratic impulse and in fact may, according to some observers, be considered to promote anti-democratic practices. This may be particularly evident where we see large-dollar philanthropists paying to play in resource-scarce public systems like education and health. In some cases, demonstrations are waged against the perception, if not the reality, of undue influence. In the case of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, critics have noted that the foundation is often the biggest donor in the room, even in venues like the World Health Organization, and this influences what should be collective agendas forged by nation-states. The foundation then supplements this agenda setting with support of media to cover an area in which the foundation is interested, thus drawing what some consider to be unbalanced public attention to the foundation’s strategy and goals.

In the United States, where there has been a lot of piling on of billionaire philanthropy in education (with questionable results), education historian Diane Ravitch feels it is “troubling” that the Gates, Broad, and Walton Family foundations, which are all large education funders, have similar agendas, because the combination of them can crowd out other voices and the truth about outcomes.

“They all support an agenda that is remarkably similar: privately managed charter schools; high-stakes testing; evaluating teachers by the test scores of their students; top-down, centralised decision-making by the federal government, the state government or the mayor; disregard for teacher experience or credentials or degrees,” says Ravitch. “. . . In the past, our great philanthropies carried out demonstration projects in [the] hope of swaying government policy. Now government policy and foundation policy are intertwined, without any evidence to support its efficacy.” 3

In the growing arena of corporate philanthropy, there is yet another dimension of philanthropy as less than disinterested and democratic. Corporate giving is on the rise, but with much of it through in-kind giving of product and services, and much of it directed to the strategic priorities of the corporate givers themselves. Moreover, despite the numbers of corporations engaged in philanthropic giving, corporate giving is as concentrated at the top by large donors as private philanthropy is with the dominance of the likes of Gates and Ford. A small number of corporations account for the vast bulk of corporate giving. Corporations give, for sure, but they have agendas, whether it is pharmaceutical companies donating unneeded product or providing philanthropic gifts related to elements of national health insurance reform, or the big banks building community support after having been tagged with bringing down much of the economy, or big-box retailers like Walmart making contributions toward buying support for or diminishing opposition to their new stores.

It appears that much of institutionalized philanthropy is still struggling relatively uncreatively where transparency and accountability are concerned, but that is unsurprising given that it has no market that can react to it in a way that would visit consequences upon it. It is certainly not that there are no consequences for bad grantmaking decisions in philanthropy, but the consequences ripple out to community and grantees rather than to the grantmaking institution, which often merely needs to keep its mouth shut, wait out the distress, and perhaps change executives for all to be forgiven.

Sector Blurring and Era Shifting

New language has entered the scene, bringing new frames of reference, but it is unclear what will stick, what will fall away, and what will morph so significantly that it will be unrecognizable. For instance, the concept of social enterprise is still evolving significantly, and, in a way, it has ended up in a healthy relationship with the concept of business planning and the best uses of philanthropic capital and in a questionable relationship with cause marketing and hybrids. But all of that is not yet fully cooked. The blurring of sectoral boundaries and the emergence of sector agnosticism appear to be producing more high-dollar grantmaking to businesses and public-sector organizations. For instance, even when the journalism scene is moving toward the nonprofit sector and becoming more of a networked enterprise, the Ford Foundation is providing multimillion-dollar grants to major for-profit journalism outlets.

In general, philanthropy is a very complicated and changing space. There are threads of more traditional approaches woven in with new and more untethered forms of giving. It is important to know one thing in all of this—nothing will stay as it is today, and, as giving changes, we must change also. While the situation we are looking at here is complicated, NPQ believes that the essence of the change that likely needs to be made by nonprofits is somewhere in the realm of engagement or in the renewal of the closeness of relationship between the giver and receiver, or at least the giver and the cause.

Notes

- Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, Giving USA 2013: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2012 (Chicago, IL: Giving USA Foundation, 2013), www .givingusareports .org.

- CFC-50 Commission, Federal Advisory Committee Report on the Combined Federal Campaign (Washington, DC: U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 2012), 2, www.opm.gov/combined-federal-campaign/cfc-50-commission/2012-report.pdf.

- Shanaz Musafer, “Power of Policy-Making in the Hands of Philanthropists,” BBC News Business, September 2, 2012, www.bbc.co.uk/news/business -19272108.