PHOTOGRAPH: “PEEP SHOW” BY SKIP HUNT

Editors’ note: This article was first published in summer 2008 and is featured in NPQ‘s special winter 2012 edition: “Emerging Forms of Nonprofit Governance.” The article is largely excerpted from the Urban Institute’s report Nonprofit Governance in the United States: Findings on Performance and Accountability from the First National Representative Study.1 The full report is available at www.urban.org/url.cfm?ID=411479.

In recent years, policy-makers, the media, and the public have increasingly focused on the accountability of nonprofit boards. Legislative reforms have been proposed, nonprofit associations have called on their members to review and strengthen nonprofit governance practices, and the Internal Revenue Service has released “Governance and Related Topics—501(c)(3) Organizations,” which includes a series of goodgovernance recommendations.2 Accordingly, nonprofits face pressure to become more accountable and transparent to their communities, their constituencies, and the public, which in turn has had a profound impact on nonprofits’ internal discussion about appropriate board roles and policies.

It is critical that both proposed policy reforms and best-practice guidelines be informed by solid knowledge about how boards currently operate and which factors promote or hinder their performance. To help ensure the availability of such knowledge, in 2005 the Urban Institute conducted the first-ever national representative study of nonprofit governance. More than 5,100 nonprofit organizations of varied size, type, and location participated in the study, making it the largest sample studied to date. The survey covered an array of topics but focused on practices related to current policy proposals and debates. This focus is in keeping with one of the Urban Institute study’s primary goals: to draw attention to the links between public policy and nonprofit governance.

In considering nonprofit governance, we have to ask not only whether nonprofit boards have mechanisms in place to avoid malfeasance but also whether they actively serve an organization’s mission. These issues are clearly applicable to the controversial area of financial transactions between nonprofits and the members of their boards of directors, one of the topics covered in the Urban Institute’s broader report.

Financial Transactions between Nonprofits and Board Members

Under the law, board members owe a nonprofit a duty of loyalty, which requires them to act in a nonprofit’s best interest rather than in their own or in anyone else’s. The IRS’s “Governance and Related Topics” cautions that “in particular, the duty of loyalty requires a director to avoid conflicts of interest that are detrimental to the charity.” Against this background, nonprofits’ purchase of goods and services from board members or their companies raises special concerns about whom such transactions really benefit. In a guide for board members, one state attorney general’s office warns that “caution should be exercised in entering into any business relationship between the organization and a board member, and should be avoided entirely unless the board determines that the transaction is clearly in the charity’s best interest.”3

In 2004 a proposal to restrict nonprofits’ ability to engage in these transactions was included in the Senate Finance Committee’s draft white paper but met considerable opposition from some nonprofit representatives. The president and CEO of Independent Sector, for instance, warned that prohibiting economic transactions “could be extremely detrimental to a number of charities. . . . Public charities, particularly smaller charities, frequently receive from board members and other disqualified parties goods, services, or the use of property at substantially below market rates.” The executive director of the National Council of Nonprofit Associations, which is composed primarily of smaller and midsize nonprofits, voiced a similar objection.4 There has also been concern about the impact on nonprofits in rural and smaller communities, where a trustee’s law firm or bank may be the only one in the area.5

But whether public charities should or shouldn’t be allowed to engage in financial transactions with board members, there is agreement that such transactions should be transparent to boards and that policies should be in place to ensure that such transactions are in a nonprofit’s best interest. The IRS’s guidelines are emphatic on this point. They call on boards to “adopt and regularly evaluate a written conflict of interest policy” that, among other things, includes “written procedures for determining whether a relationship, financial interest, or business affiliation results in a conflict of interest” and specifies what is to be done when it does.6 Further, the IRS has instituted a question on its Form 990 asking nonprofits whether they have a conflict-of-interest policy in place.

Results from the Urban Institute’s survey shed light on (1) the scope of such transactions; (2) whether these transactions provide claimed benefits for nonprofits; and (3) how nonprofits’ current practices measure up to conflict-of-interest standards from the IRS and others.

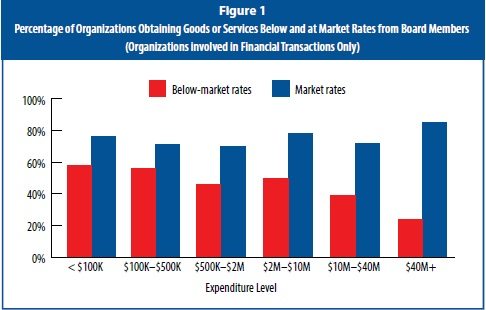

Frequency and Consequences of Financial Transactions

SOURCE: 2005 Urban Institute National Survey of Nonprofit Governance

According to respondents’ self-reports, financial transactions between organizations and board members are extensive, particularly among large nonprofits. Overall, 21 percent of nonprofits reported buying or renting goods, services, or property from a board member or affiliated company during the previous two years. Among nonprofits with more than $10 million in annual expenses, however, the figure climbs to more than 41 percent.7 But also note that among nonprofits that say they did not engage in transactions with board members or affiliated companies, 75 percent also say they do not require board members to disclose their financial interests in entities doing business with the organization. In effect, respondents may be unaware of transactions that have taken place.

According to respondents, among the 21 percent of nonprofits that engaged in financial transactions with board members or related companies, most obtained goods at market value (74 percent), but a majority (51 percent) report that they obtained goods at below-market rate. Less than 2 percent reported paying above-market cost.8 Keep in mind too that these are self-reports, so if anything, the figures are likely to underreport transactions resulting in obtaining goods at above-market value or at market value and to overreport transactions resulting in obtaining goods at below-market rate.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Among nonprofits that engaged in financial transactions with board members, small nonprofits were considerably more likely than large ones to obtain goods and services from board members at below-market cost: 58 percent of nonprofits with less than $100,000 in expenses obtained goods or services at below-market rate from a board member, but the percentage drops to a low of 24 percent among nonprofits with more than $40 million in expenses (see figure 1). In contrast, the percentage of nonprofits that received goods or services at market value was more than 70 percent for each size group.9 The percentage reporting they obtained goods at above-market value was less than 3 percent for each size group.10

The study also found no evidence that bans on financial transactions would disproportionately affect rural nonprofits. There was no significant difference between nonprofits inside and outside metropolitan statistical areas either in the percentage engaged in financial transactions or in the perception of how difficult it would be for them were such transactions prohibited.

Forty-five percent of nonprofits that engaged in business transactions with trustees said it would be at least somewhat difficult were they prohibited from purchasing or renting goods from board members, but only 17 percent said it would be very difficult. Percentage differences by size were not statistically significant. As one would expect, the comparable figures rise among those who obtained goods or services at below-market rate. Fifty percent said it would be at least somewhat difficult, and 19 percent said it would be very difficult.

Policies to Regulate Financial Transactions and Conflicts of Interest

SOURCE: 2005 Urban Institute National Survey of Nonprofit Governance

Policies to Regulate Financial Transactions and Conflicts of Interest

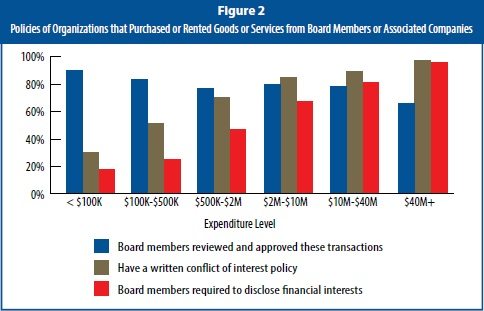

Among all respondents, only half had a written conflict-of-interest policy, and only 29 percent required disclosure of financial interests. Among nonprofits that reported financial transactions with board members, 60 percent have a conflict-of-interest policy, and 42 percent require board members to disclose the financial interests they have in companies that do business with the nonprofit. As we can see, substantial percentages of nonprofits—including those engaged in financial transactions with board members—do not meet the standards laid out by the IRS and other good-governance guidelines. But the majority of nonprofits engaged in such transactions (82 percent) report that other board members had reviewed and approved the transactions beforehand.

Substantial variations among respondents do exist by size (see figure 2). Larger nonprofits are more likely to have a written conflict-of-interest policy. Among those engaged in financial transactions, almost all nonprofits with more than $40 million in expenses have a written conflict-of-interest policy (97 percent), but the figure decreases to only 30 percent among nonprofits with less than $100,000. Financial disclosure requirements also vary considerably by size. Among nonprofits engaged in financial transactions with board members or associated companies, the percentage that requires disclosure ranges from a low of 18 percent among the smallest nonprofits to a high of 96 percent of nonprofits with more than $40 million in annual expenses. Substantial minorities in the $2-million to $40-million size categories and majorities in all groups of less than $2 million do not require disclosure.

Although formal policies are more common among larger nonprofits, smaller nonprofits are more likely to report that other board members reviewed and approved transactions. Ninety percent of nonprofits with less than $100,000 had other board members review transactions beforehand, but the figure declines to 66 percent among those in the more-than-$40-million category. In the case of smaller nonprofits, one issue is that while board members may review transactions, they often lack written guidelines to inform their review. Among larger nonprofits that have formal policies, significant percentages of nonprofit boards do not review transactions beforehand to ensure that formal policies have been met.

Conclusions and Implications

Our findings demonstrate that substantial variations in boards exist among nonprofits of different types. Given that variation, those proposing policy initiatives and good-governance guidelines to strengthen nonprofits should assess the different impact on various types of nonprofits and weigh them carefully. So, for example, our research supports the argument that prohibiting financial transactions with board members would disproportionately hurt small nonprofits.

Our findings show that many nonprofits are engaged in buying or renting goods and services from board members, which sometimes yields savings in terms of below-market rates—but more often, it does not. Our findings do not tell us whether these practices are in the best interest of a nonprofit, but they strongly confirm that this is an important area in which appropriate policies and procedures need to be in place. Smaller nonprofits that engage in financial transactions need to have more formal mechanisms in place to regulate transactions, and larger organizations need to institute practices more frequently in which board members unrelated to these transactions review transactions for appropriateness. Furthermore, research is needed to examine the content of these policies and procedures and whether they are adequate to ensure that transactions do not undermine board members’ duty to act in an organization’s best interest and to help inform policy proposals and best-practice guidelines aimed to achieve that goal.

Notes

- Francie Ostrower, Nonprofit Governance in the United States: Findings on Performance and Accountability from the First National Representative Study (Washington: DC: Urban Institute Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy, June 25, 2007), www.urban.org/url.cfm?ID=411479.

- Editors’ note: The IRS originally released its recommendations in the draft paper “Good Governance Practices for 501(c)(3) Organizations” (www.irs.gov/charities/article/0,,id=178221,00.html), cited in the original Urban Institute report. The IRS has now replaced the paper on its website with “Governance and Related Topics—501(c)(3) Organizations.” The new IRS paper offers many of the same governance recommendations (www.irs.gov/pub/irs-tege/governance _practices.pdf).

- Web page of the New Mexico Attorney General (www.ago.state.nm.us/divs/cons/charities/nmboardguide.htm).

- “Comments on Discussion Draft on Reforms to Oversight of Charitable Organizations” (www.independentsector.org/PDFs/roundtable.pdf). See also the statement submitted by Audrey R. Alvarado, executive director of the National Council of Nonprofit Associations, to the Senate Finance Committee, which cautions against the “undue hardship” for small and medium-size nonprofits, July 21, 2004 (www.senate.gov/~finance/Roundtable/Audrey _A.pdf).

- See, for example, Marion R. Fremont-Smith’s comments to the Senate Finance Committee, July 13, 2004 (www.senate.gov/~finance/Roundtable/Marion _F.pdf).

- www.irs.gov/pub/irs-tege/governance _practices.pdf.

- By size categories, the percentages are as follows: less than $100,000: 15 percent; $100,000 to $500,000: 18 percent; $500,000 to $2 million: 27 percent; $2 million to $10 million: 34 percent; $10 million to $40 million: 42 percent; and more than $40 million: 45 percent.

- Percentages exceed 100 because nonprofits could engage in multiple financial transactions with board members so that any organization could report up to three categories.

- Ostrower, “Nonprofit Governance in the United States.” Note that percentages obtaining goods at market rates and below-market rates exceed 100 because nonprofits could engage in multiple financial transactions with board members, and therefore any nonprofit could report in both categories.

- Ibid.