October 21, 2019; Guardian

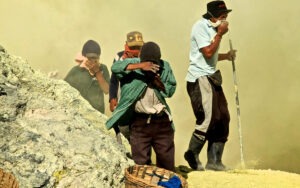

For the next year, the Guardian will run a high-profile series called Our Unequal Earth, which will look at the greater impact ecological hazards and climate disasters have on people of color and low-income communities. The UK publication has a new environmental justice reporter in Nina Lakhani, and to launch the series, she asked five leaders in the environmental justice movement to answer a question that had to do with the reasons behind their focus on environmental justice.

We bring you excerpts from what they said, but it is well worth checking out the article as a whole. You may wish to monitor the series, and perhaps even contribute to it.

Dr. Robert Bullard, distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University:

The seminal Environmental Justice principles adopted by the National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991…became the foundation for social justice movements across the world. Even so, the same discrimination and racism continues to dictate who gets dumped on and who gets resources to mitigate floods, wildfires and other disasters. Of course, those with wealth and political clout do best; if you have money, you can buy bottled water or move house. The poor cannot go anywhere.

Kandi Mossett-White of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation in North Dakota, the native energy & climate campaign coordinator at Indigenous Environmental Network:

I grew up in a community full of environmental injustices without knowing it. So many people I knew—young and old, men and women—got cancer, including me during my second year in college. I thought this was normal. Our territory is contaminated by the coal industry, uranium mining, overfertilization, and oil. But environmental injustice is a tangled web; it’s about so much more than pollution. Whenever there’s a new megaproject, the area is overwhelmed by men, there’s an influx of money and a rise in organized crime. After the oil boom in 2007, the number of missing and murdered indigenous women increased, and so did drugs. Gangs came and recruited our young people to sell drugs and many of these young men are now in jail or dead.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Mustafa Ali, policy expert and community organizer, and former head of the EPA environmental justice program:

Environmental injustice is about [the state] creating sacrifice zones where we place everything which no one else wants. The justification is always an economic one, that it makes sense to build chemical plants on so-called cheap lands where poor people and people of color live, but which are only cheap because all the wealth and economic opportunities have been stripped out. The people who live in these areas are unseen, unheard and undervalued.

Jamie Margolin, climate justice youth activist, organizer, and founder of #ThisIsZeroHour:

For me, the climate crisis has been looming over my entire life—and future. Three things happened in 2017 which motivated me to act: the US leaving the Paris agreement, Hurricane Maria destroying Puerto Rico, and the wildfires in Canada, which created a thick layer of smog over Seattle that felt apocalyptic. At the beginning, my dream with the #ThisIsZeroHour campaign was to mobilize a lot of people for a youth climate march, but it’s got bigger and bigger and we now have a hundred chapters. So far it has been very US-focused, but that’s changing.

LeeAnne Walters, Flint resident and community activist:

Sit down in your groups and communities and figure out people’s strengths. You will have defeats—use those as learning experiences. You will have victories, rejoice when those happen. Our environment plays a huge role in our health and future generations’ health, so it is our duty as ordinary people to protect it and fight back. We can make a difference.

The series is funded by the Schmidt Family Foundation and, in our view, may be a major step forward in bringing an environmental justice focus to mainstream reporting.—Ruth McCambridge