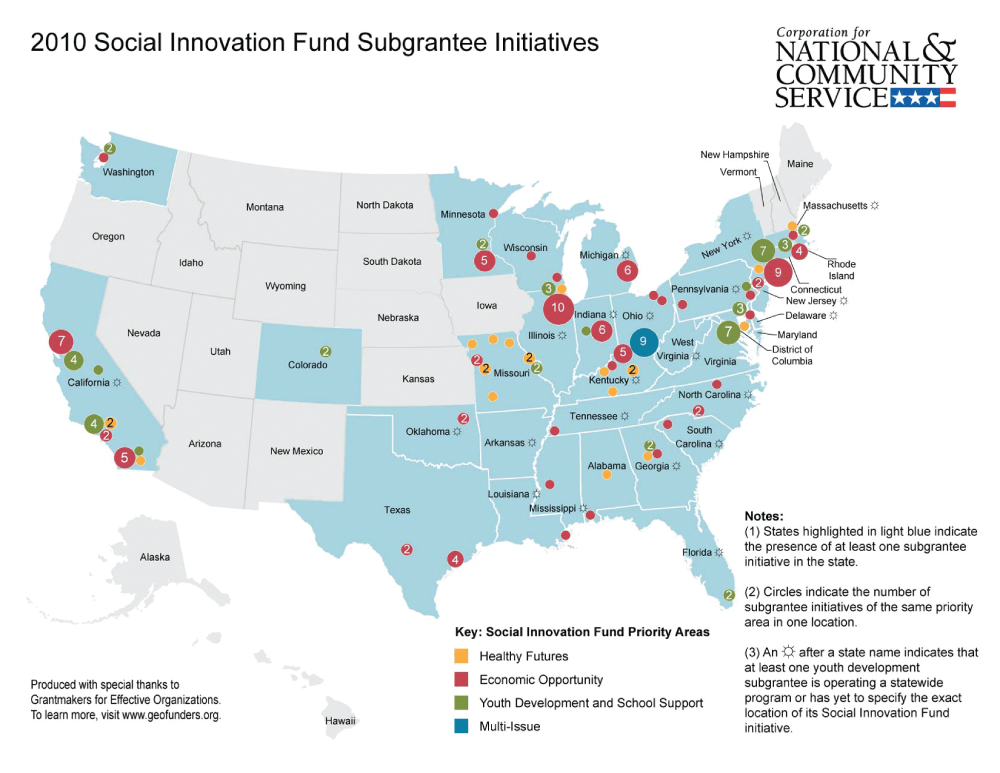

To take a closer look at the map and find out more about the SIF process visit the CNCS website.

Eleven intermediary organizations have now received $49.3 million in grant funding in the inaugural 2010 Social Innovation Fund (SIF) competition to implement programs in three priority areas, according to the Corporation for National & Community Service (CNCS) website: economic opportunity, healthy futures and youth development.

Over 500 organizations competed for the grants and 138 were selected as sub-grantees. A wide range of organizations are represented among the sub-grantees, according to CNCS, including community foundations, local non-profit organizations, faith-based organizations, academic institutions, local public agencies and more.

Though 31 states across the country now have a subgrantee presence, an all-too-usual pattern of underinvestment in fly-over states has been revealed in the the SIF grant process.

The Urban Dictionary defines “fly-over states” as the “states in the middle of the United States that . . . are generally flown over when traveling from coast to coast.” It appears that the Social Innovation Fund is the latest to pass over Nebraska, Utah, Wyoming, and Montana – as well as North Dakota, South Dakota, Idaho, Iowa, Arizona, Kansas, and New Mexico (in addition to non-fly-over states Alaska, Hawaii, and Oregon and the northern New England states, Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont) – in the identification of subgrantees that will be receiving funding (PDF).

It could just be the numbers. There are more people and more nonprofits in highly populated urban areas – explaining why the San Francisco Bay Area is the focus of 11 SIF subgrantees, Chicago 14, the Twin Cities of Minnesota 7, New York City 17, Cincinnati 12, metro Washington D.C. 7, and Los Angeles 8. As a demonstration program of sorts, with only $50 million in federal funding (to be matched by both grantees and subgrantees), the SIF wasn’t obliged to distribute its moneys according to some implicit or explicit geographic balance.

But this is more than a little imbalance. The fly-over states bypassed by the SIF are largely rural states. The fate of rural nonprofits and rural communities in the SIF competition was a concern from the beginning. In an August 2009 missive to the SIF program managers, a number of the nation’s top rural advocates from the Center for Rural Affairs, the Center for Rural Strategies, and the West Central Initiative outlined why rural communities would be great sites for the SIF – and why the structure of the Fund might work against rural communities (PDF).

Unlike urban areas, the statement said, “modest investments in a rural area can serve a high proportion of those targeted by a specific innovation – making it easier to observe and measure the innovation’s effectiveness and impact.” Moreover, “rural systems have fewer players – often making it easier to isolate cause and effect and measure outcomes.” In other words, to the extent that the Social Innovation Fund was meant to test and experiment with the replication of “proven” innovations, rural communities fit the bill. But as many observers noted, there was little innovation in the SIF grantees – little that looked like it was meant to experiment with new ideas.

If viewed as simply another federal grantmaking program to regrantmaking intermediaries with high match requirements, the SIF would be stacked against rural areas in a number of ways:

· Many, perhaps most potential regrantmaking intermediaries have little or no connection to rural areas, making them unlikely to pick rural subgrantees;

· The minimum grant size of $100,000 is a large grant for many rural nonprofits, frequently with total budgets not much larger than the smallest SIF grants;

· The 1-to-1 matching fund requirement presents a difficult hurdle for rural nonprofits with limited or no access to foundations and other funders that could provide the necessary money to get to the table;

· Few rural groups have the excess staff capacity to devote to writing challenging responses to complex RFPs like the funding announcement from the Fund.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The map of SIF subgrantee service areas actually understates the minimal inclusion of rural areas in the SIF program. Several subgrantees are identified serving statewide areas, but it is all but assured that urban communities in those states will benefit as much as or more than their rural counterparts.

There are some SIF grantees that have picked subgrantees with explicit rural service geographies. The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation has selected a few subgrantees intended to service rural areas, including the Children’s Aid Society’s Carrera Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Program in Arkansas, Georgia, South Carolina, Oklahoma, and North Carolina and the Gateway to College National Network to potentially expand to statewide service areas in Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee, in addition to its current activity in states such as South Carolina, North Carolina, and California.

One of the smaller SIF grants went to the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky, which will use its SIF grant to expand access to health services in three rural areas in addition to an urban-focused programin Louisville. The National Fund for Workforce Solutions has pickedthe Foundation for the Mid South (full disclosure: the FMS CEO is a member of NPQ’s board of directors) for the Delta Workforce Funding Collaborative. And the AIDS United grant to the Montgomery AIDS Partnership will support a tele-health initiativeserving 47 counties in rural Alabama.

Rural America is 20 percent of the population of the U.S., but hardly 20 percent of the SIF grant funds. Besides the fact that most intermediaries do not have rural in the forefronts of their minds, thus leading to the underfunding of rural “innovations,” the states completely missed in the SIF geography of subgrantee grants reflect the states that have been historically undercapitalized in terms of foundation grantmaking.

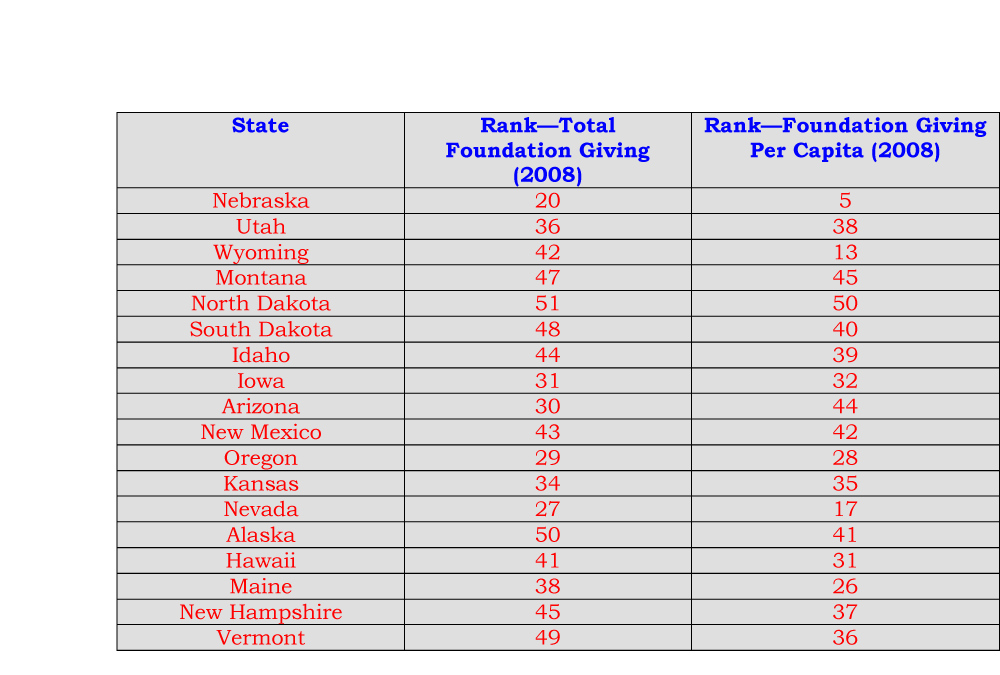

The nonprofits in these states have little access to the philanthropic assets that the typical SIF subgrantee had to show as a match to qualify. Their ranks in philanthropic assets and philanthropic grantmaking tell you that SIF’s fly-over states have also been skipped by much of U.S. philanthropy:

In terms of assets, most of these states are philanthropically undercapitalized. Among the dozen states with the lowest total amount of foundation assets are Alaska, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, New Hampshire, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Idaho. These states also lack a SIF presence.

The SIF list of subgrantee service areas misses a huge swath of states and communities, largely those that were structurally disadvantaged in the SIF competition’s emphasis on large grants and at least dollar for dollar matching funds.

The SIF will decide upon its new grantees for the second round of funding in August 2011. Its materials report that its newest slate of potential grantees come from 14 states, 10 of which are from states where grantees are not currently funded. This does not, however address where the subgrantees might be located.

NPQ offers these observations in the hopes that as the 2011 round of grantees are chosen that more care will be given to ensuring that this program corrects the relative lack of philanthropic investment in these “fly-over” areas. The degree to which the situation can be substantively corrected is questionable, however, since the majority of the funding in 2011 will go to continuation grants for current grantees.

When asked about the distribution consideration for subgrantees, a spokesperson for CNCS sent a statement that reads in part: “The distribution of the Social Innovation Fund subgrantees by the initial round of awards to Social Innovation Fund intermediaries is the result of the subgrant processes that each intermediary independently completed. The Corporation was not involved in the selection of subgrantees. The distribution was, of course, influenced by the Corporation’s selection of the intermediaries, each of which identified specific low-income communities that would (or likely would) be served by their programs.” The statement says that general geographic distribution was taken into account during the last round and would be taken into account again in the current round.

That said, it appears that subsequent rounds of SIF awards will continue to leave a significant part of the heartland of America sparsely populated with SIF subgrantees. The problem is in the structure of the program – its reliance on the geography of philanthropic capital as a crucial requirement for SIF participation. More attention to the geographic imbalance of SIF subgrantees is all well and good, but unless structural modifications are made to the program, it is difficult to imagine that the issue will be redressed in current and future funding awards.

For more information about SIF applicants, take a look at the applicant profiles from CNCS here (PDF).