This article from the fall 2020 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly introduces a series of works on the subject of environmental justice and Indigenous communities in the United States, curated by Raymond Foxworth of the First Nations Development Institute. Look for more articles in this series, and watch this exclusive webinar on the topic featuring three of the authors, hosted by Senior Editor Steve Dubb.

I am excited to kick off this first ever series for the Nonprofit Quarterly magazine focused on environmental justice and Indigenous communities in the United States. Too often, Native voices in all aspects of American life are silenced and marginalized, and this has continued to be the case in the global environmental justice movement. This series is an attempt to bring Native leaders working for environmental justice in their communities into the conversation, to speak for themselves and discuss how they are mobilizing to stop environmental degradation and racism and build more sustainable futures for their communities and beyond.

Native lands today, once thought to be barren and desolate areas fit only for Indians, cumulatively occupy over 55 million acres of land and 57 million acres of subsurface mineral estates.1 The lands of Native nations sit on top of “nearly 30 percent of the nation’s coal reserves west of the Mississippi, as much as 50 percent of potential uranium reserves, and up to 20 percent of known natural gas and oil reserves.”2 In all, according to the Department of Energy, Native lands today house over 15 million acres of potential energy and mineral resources—and nearly 90 percent of those resources are untapped.3

Economists Shawn Regan and Terry Anderson have noted that Native communities, especially in the Western United States, are “islands of poverty in a sea of wealth.”4 Some economists have suggested that Native nations exploit these resources for economic gain, to lift themselves out of poverty and enable local community development. In fact, federal policy-makers and extractive industry lobbying groups have long advocated for reducing barriers for Native nations and people to lease these valuable resources to mostly non-Native companies for exploitation and development. Historically, Congress and their extractive industry allies sought to exploit Native lands and resources without Tribal input and consultation or by diminishing Tribal lands.5 Deals surrounding non-Native access and use of Native lands and resources were the subject of one of the largest settlement cases involving mismanagement and neglect of Native lands and interests by the federal government.6

But today, as highlighted by the expert contributors to this issue, Native nations are reversing histories of exploitation by the federal government and other accomplices. Native nations and Native organizations are actively fighting for the protection of local resources. Moreover, the leaders at the helm of this special issue all highlight place-based efforts to advance Indigenous environmental justice, rooted in Indigenous knowledge and epistemologies. These authors make clear that U.S. settler-colonialism continues to be a driving force behind the deterioration and contamination of Native lands, but also that Indigenous peoples are not subjugated, passive victims of “modernity” but rather are taking active stances to fight for justice. Finally, all the authors make clear that for modern environmental and climate justice movements—and philanthropic support of these movements—to be truly impactful, they must let Indigenous peoples lead.

Indigenous Peoples and Environmental and Climate Justice Movements

Historically, environmental movements have not been an ally to Indigenous peoples and communities. For example, the early conservation movement in the United States lobbied to create the national park system that displaced and expelled Native peoples from their homelands and hunting grounds, in an effort to keep these lands in a pristine “state of nature.” Originating with Yosemite National Park in the Sierra Nevada mountains around the 1850s (during the California Gold Rush), conservationists were backed with the full might of the U.S. Army to push Native peoples from lands that they had occupied for thousands of years. Seen as a model for successful land and natural resource protection, this system has been exported around the world.7

This colonial and violent past continues to plague conservation, climate, and environmental justice organizations today. Indigenous communities across the globe continue to be displaced (sometimes with violence) and marginalized by NGOs claiming to advance environmental and climate justice.8 In part, this kind of racism and violence perpetrated against Indigenous peoples is motivated by Western environmental organizations assuming Indigenous people have little or nothing to contribute to environmental and climate justice.

But Indigenous people have critically important knowledge systems and practices. For example, as fire archaeologist Hillary Renick has noted, wildfires across the globe have been linked to changes in climate that have created warmer, drier conditions, and increased droughts; and there is growing recognition that traditional Indigenous land practices prevent forest fires. Calls for the integration of Indigenous traditional fire ecology into mainstream land management practices are also growing.9

Beyond their colonial and racist origins, and inability to acknowledge that traditional Indigenous knowledge can advance climate and environmental justice, the modern climate and environmental movements perpetuate Indigenous marginalization and exclusion in terms of their composition. Environmental organizations in the United States largely remain segregated; the most recent and publicly available data note that 80 percent of boards of directors and 85 percent of staff of environmental nonprofits are white. These organizations not only lack diversity but have also become less and less transparent in their reporting of staff and board compositions.10 At the same time, funders have done relatively little to meaningfully push the environmental and climate justice movements to be more diverse and inclusive, in large part because they are also rooted in whiteness.11

Philanthropy and the Funding of Indigenous Environmental Movements12

Despite the long history of Native resistance to exploitive and harmful forms of energy and resource development, philanthropic investment in Native environmental justice movements mirrors their overall marginal investments in Native communities.13

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

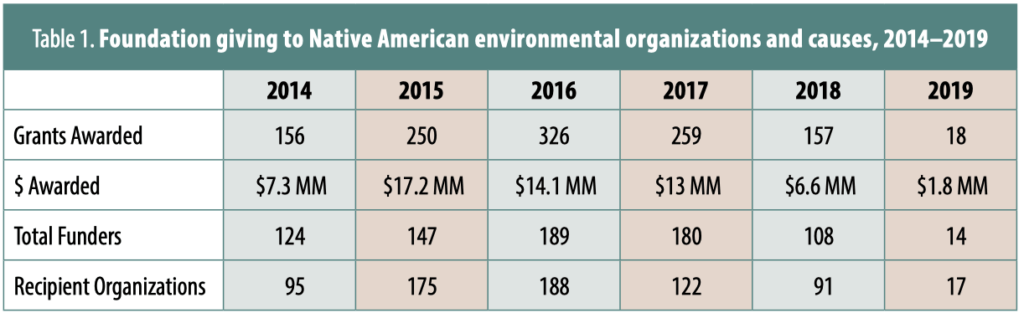

According to data made available by two nonprofits, Candid and Native Americans in Philanthropy, foundations awarded 1,166 grants totaling roughly $60 million between 2014 and 2019 to Native American environmental and animal organizations and causes. On average, foundations award roughly 194 grants totaling about $10 million annually to these organizations and causes (an average grant size of $51,450).14

As a percentage of total foundation giving, the best available data suggest that about 3 percent of total foundation giving goes to environmental causes.15 This means, on average, that foundations gave a little over $2 billion to environmental causes annually between 2014 and 2019. Only a total of 0.5 percent (five-tenths of one percent) of total foundation environmental giving was awarded to environmental organizations and causes in Native communities.

As the giving data in Table 1 note, the highest year of giving to Native American environmental organizations and causes was 2015, followed by 2016. From 2014 to 2019, the majority of grant dollars was awarded to the top five grant recipients in each year. Among those top five recipient organizations in each of the six years, seventeen were Native-controlled organizations or Native nations, and thirteen were non-Native-controlled organizations. Although a majority of Native organizations appeared in the top tier of giving each year, 56 percent of the resources to these top recipients was awarded to the non-Native-controlled organizations. This is consistent with other research that has identified that non-Native-controlled organizations receive a large amount of resources that are intended to support Native community-based work. Moreover, this research has uncovered that Native organizations receive smaller grants for similar work.16

The top two high years of foundation giving (2015 and 2016) do coincide with large and very public events in Native communities. It was in 2016 that Water Protectors gripped national headlines as they mobilized to protect land and water on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota, fighting against the Dakota Access Pipeline.17 Also starting in 2015, Native nations and organizations were at the peak of their organizing, advocating to get Bears Ears in southern Utah designated as a national monument.18

The vast majority of funding provided by foundations for the past five years has been in the natural resource subject area, as identified by Candid. This includes work targeting energy resources, water and water management, air quality, and more. The second highest subject area of support is biodiversity, including forest preservation, plant biodiversity, and wildlife biodiversity.

What do these data tell us about support of Native environmental justice movements in the United States? In sum, they tell us that Native environmental organizations and causes receive minimal support from foundations.

The amount of foundation support for Native-led change is even smaller. In our work to support environmental justice in Native communities, the communities often express extreme frustration with non-Native-led organizations, which receive grant dollars to do work in or for Native communities. These non-Native organizations bring their own assumptions and values to environmental justice work, and there is no guarantee that Native people are actually meaningfully involved. The lack of investment in Native-led change and the dismissal of community-based knowledge in promoting environmental justice firmly entrench models of philanthropic colonialism in Native communities.

Supporting Native-Led Environmental Justice Movements

The climate and environmental justice movements, as well as the philanthropic organizations that support them, have a long way to go to be substantively inclusive of Native communities around climate and the environment. Centering Indigenous communities and their ways of knowing will go far in developing a more just society for all. Here are some steps that funders and environmental NGOs can take:

- Get educated: Educate yourself about Native issues, lands, and environmental activism. This includes educating yourself on the theft of Native lands and resources, and how this has contributed to U.S. development. This article series is one good start at self-education.

- Connect with Native organizations: There is no shortage of Native organizations doing environmental and climate-related work. Form intentional, meaningful connections with these organizations and Native leaders.

- Invest in Native organizations: Philanthropy needs to invest in Native environmental and climate justice work.

- Move beyond whiteness: Philanthropy and mainstream environmental and climate justice organizations need to move beyond white-centered frameworks in advancing justice. Indigenous peoples have time-tested knowledge systems that are invaluable to advancing environmental and climate justice.

Notes

- S. Department of the Interior, Office of the Special Trustee for American Indians (OST), “OST Statistics and Facts,” accessed August 23, 2020.

- Maura Grogan, with Rebecca Morse and April Youpee-Roll, Native American Lands and Natural Resource Development (New York: Revenue Watch Institute, 2011), 3.

- Department of Energy, “Department of Energy Makes Up To $11.5 Million Available for Energy Infrastructure Deployment on Tribal Lands,” February 16, 2018.

- Shawn Regan and Terry L. Anderson, “The Energy Wealth of Indian Nations,” LSU Journal of Energy Law and Resources 3, no. 1 (Fall 2014): 195.

- Johnnye Lewis, Joseph Hoover, and Debra MacKenzie, “Mining and Environmental Health Disparities in Native American Communities,” Current Environmental Health Reports 4, no. 2 (June 2017): 130–41.

- “Government Settles Indian Trust Fund Suit,” Cultural Survival, accessed August 19, 2020.

- Philip Burnham, Indian Country, God’s Country: Native Americans and the National Parks (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2000); Heidi Glasel, Review of Disposing of Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks by Mark David Spence [note: the reviewer made a mistake in the title, which correctly is Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks] and American Indians and National Parks by Robert H. Keller and Michael F. Turek, American Indian Quarterly 25, no. 2 (2001): 313–15; and Robert H. Keller and Michael F. Turek, American Indians and National Parks (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1998).

- Patrick Barkham, “Human rights abuses complaint against WWF to be examined by OECD,” Guardian, January 5, 2017; Katie J. M. Baker and Tom Warren, “A Leaked Report Shows WWF Was Warned Years Ago Of ‘Frightening’ Abuses,” BuzzFeed News, March 5, 2019.

- Hillary Renick, “Fire, Forests, and Our Lands: An Indigenous Ecological Perspective,” Nonprofit Quarterly, March 16, 2020; and see Thomas Fuller and Matthew Abbott, “Reducing Fire, and Cutting Carbon Emissions, the Aboriginal Way,” New York Times, January 16, 2020.

- Dorceta E. Taylor, Diversity in Environmental Organizations: Reporting and Transparency, Report No. 1 (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan School for the Environment and Sustainability, January 2018).

- “2019 Transparency Report Card,” Green 2.0, accessed August 17, 2020.

- The analysis and calculations that follow are the author’s own, based on data obtained from Candid and Native Americans in Philanthropy. See Native Americans in Philanthropy, “Investing in Native Communities.”

- First Nations Development Institute, Growing Inequity: Large Foundation Giving to Native American Organizations and Causes, 2006–2014 (Longmont, CO: First Nations Development Institute, 2018), 33; and see Native Americans in Philanthropy, “Investing in Native Communities.”

- Analysis and calculations are the author’s own, based on data obtained from Candid and Native Americans in Philanthropy.

- Giving Compass, “Welcome to Animal Philanthropy: A Collection By Animal Grantmakers,” May 27, 2020.

- First Nations Development Institute, Growing Inequity.

- Alison Cagle, “Still Standing: Youth activism and legal advocacy work hand in hand in the fight for justice,” Earthjustice, July 6, 2020.

- Utah Diné Bikéyah Tribe, “Native Wisdom Speaks at Bears Ears National Monument: Will America Listen?,” media kit, 2017.