October 17, 2016; Washington Post

This has been an unusual election season, and so it is difficult to predict how current students will use information from the past year and a half to shape their future political involvement. A recent poll by Scholastic, an educational publishing company that has been conducting presidential polls with K–12 students since 1940, had Clinton beating Trump with 52 percent of votes. Still, even polls like this, representing about 153,000 K–12 students nationwide, can’t address the issue of engagement—how personally involved students feel with a particular issue.

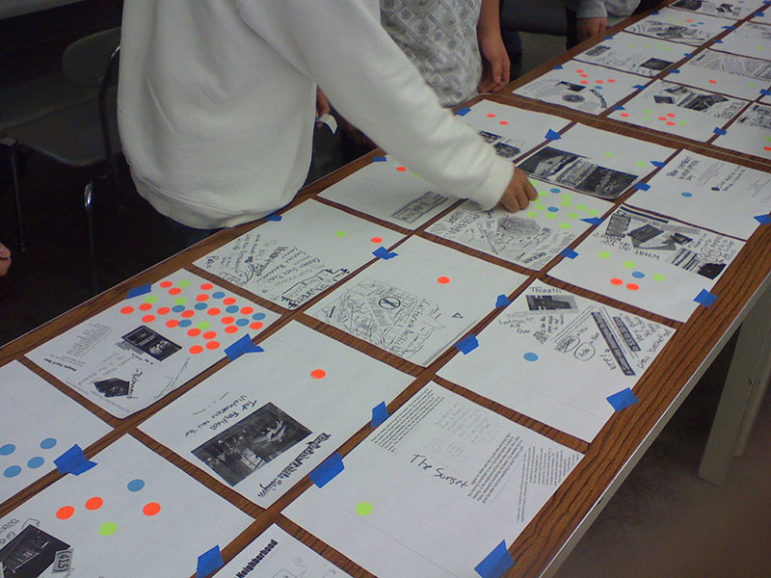

Already, about 18 U.S. cities, including Boston, Chicago, and New York, have been experimenting with a process known as participatory budgeting (PB) and looking closely at the impact on students. A few recent studies have revealed that the process “can open up the black box of policy making” and provide “a profound civic education.”

According to a recent essay by Celina Su, the Marilyn J. Gittell chair of urban studies at the CUNY Graduate Center and a board member of New York City’s participatory budgeting steering committee, PB began in 1989 in Brazil and first appeared in the U.S. in 2010 when some Chicago residents were authorized to weigh in on the city’s discretionary funding decisions. Boston initiated the first youth-led PB process in an effort that has become known as “Youth Lead The Change,” wherein any resident can suggest ideas but only young people have the power to vote. Boston’s most recent round of the program will award a total of $1 million to support a range of initiatives, including more trash cans and recycling bins, a job and resource finder app, park renovations aimed to enrich the lives of people with disabilities, free Wi-Fi and charging stations at area bus stops and similar locations, flatscreen TVs in schools that’ll serve as “digital billboards,” and an app to lead people to special outdoor study spaces.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As NPQ noted in its nonprofit newswire reporting on participatory budgeting in 2012 and 2013 (see here and here), New York City has been involved with PB since 2011–2012, when the City Council voted to test the process in four districts. The program has grown in the past five years, with the fourth cycle year (2014–2015) involving 50,000 adults and young people age 14 and older who voted on the allocation of more than $30 million of City Council funds. The New York Participatory Budgeting Research Board conducted a survey of the process by analyzing a random sample of 7,420 surveys from the 22,000 surveys that they received. According to Su, the results reveal that PB “has brought in many traditionally marginalized citizens—including young people.”

In addition to analysis of data from 2015, Su and her team also conducted 80 interviews with past and present participants, which included 24 students. The findings show promise for PB’s impact on boosting civic engagement and suggest three additional conclusions about student involvement in the process:

- When peers contact them, more young people get involved.

- Young people learned new skills and gained confidence through the process.

- Young people will get involved if it is fun and if doing so builds trust with authority figures.

Even with this analysis on this recent data, there is still some uncertainty about the long-term effects of the program. As an example of the kinds of questions that remain, Su writes, “When a participant’s beloved project doesn’t win funding, does she feel more frustrated and alienated than before, or might she then find alternative ways to mount the project?”

In an attempt to answer her own question, Su offers, “The answers, of course, may depend on more than the PB process; they may also depend on whether local government actually responds to her concerns.” In a follow-up phone conversation, Su cited a New York-based nonprofit, PTAlink.org, that aims to increase the power and legal resources of New York City’s PTAs, which was a recent outgrowth of the city’s PB process. Su has hopes to conduct a longitudinal study to look at the impact the program has in mobilizing people in support of issues that they care about—but that will take time.—Anne Eigeman