This article is the fifth in a series of personal essays that NPQ, in partnership with Tony Pickett of the Grounded Solutions Network and Marcus Littles of Frontline Solutions, is publishing in the coming weeks. Titled Black Male Leadership: Nonprofit Voices, Truth, and Power, the objective of this series is to lift up Black male voices to highlight the challenges Black male leaders in the nonprofit sector face, as well as the sector as a whole—amid ongoing anti-Black violence and the disparate racial impact of COVID-19. You can read prior entries here, here, here, and here.

The recent global awakening to racial injustice within the United States may represent an unprecedented opportunity for transformative social change—especially for Black communities, who have languished under persistent forces of exclusion, marginalization, and physical threat of violence. In many ways, only the turbulent periods marked by the US civil rights movement or the dismantling of South African apartheid compare.

Yet, despite many characterizations of this moment as a historic opportunity for real lasting change, I find myself skeptical—if not quietly offended—by widescale claims of realizing the pervasiveness of racial injustice after so many examples of racial atrocity proved insufficient to generate similar outcries over the past few years. Indeed, inequity is not a new phenomenon. After 20 years of nationwide organizing to build power within struggling communities, I continue to find myself underwhelmed, perhaps distrustful of the false certainty or righteous collective outrage that dominates contemporary political discourse. Despite this, somehow, I avoid paralyzing cynicism and remain curious about the state of the nation.

Specifically, as a husband and father, I wonder how others are thinking about shaping civil society. How are we imagining communities of choice, or “thriving,” for example? As a Black man, I wonder to what extent I can expect meaningful social change to occur in ways that respond to the myriad forms of generational disenfranchisement imposed on my ancestors for centuries. For example, how high can I set expectations for change without simultaneously exposing myself to near-certain pain and frustration or making myself susceptible to extreme disappointment? As a leader of a national philanthropy-serving organization and a peer to several networks of caring individuals committed to changing the world, I wonder what is possible through our cooperative planning and strategic coordination. For example, what would be possible if we committed to cultivating and leveraging our collective genius?

Upon further reflection, I wonder about many things for which I have not yet identified a welcoming space for unfiltered expression. This includes interrogation into why the tragic deaths of young people such as Mike Brown, Trayvon Martin, and Sandra Bland or the soul-crushing murder of Philando Castile by a police officer in front of his child were not enough to trigger similar outpourings of emotion before now.

The simple truth is this: I wonder about so many things because I want to believe there is purpose in the historic struggle of Black, indigenous, and other populations, including my own struggles. I want to believe that society is craving for its soul to be fed, and that I have completed the 10,000-plus hours required to develop a level of self-mastery sufficient for adapting to and overcoming any adversity. I want to believe that working twice as hard as the next person creates unique access to opportunities in the most unlikely of scenarios, and that this time around, the luster of political outrage will not fade away and be overshadowed by predictable forces of backlash. I want to believe that I am more than enough to lead through these times, through this uncertainty. Yet doubt is never far away, always looming, threatening to intervene.

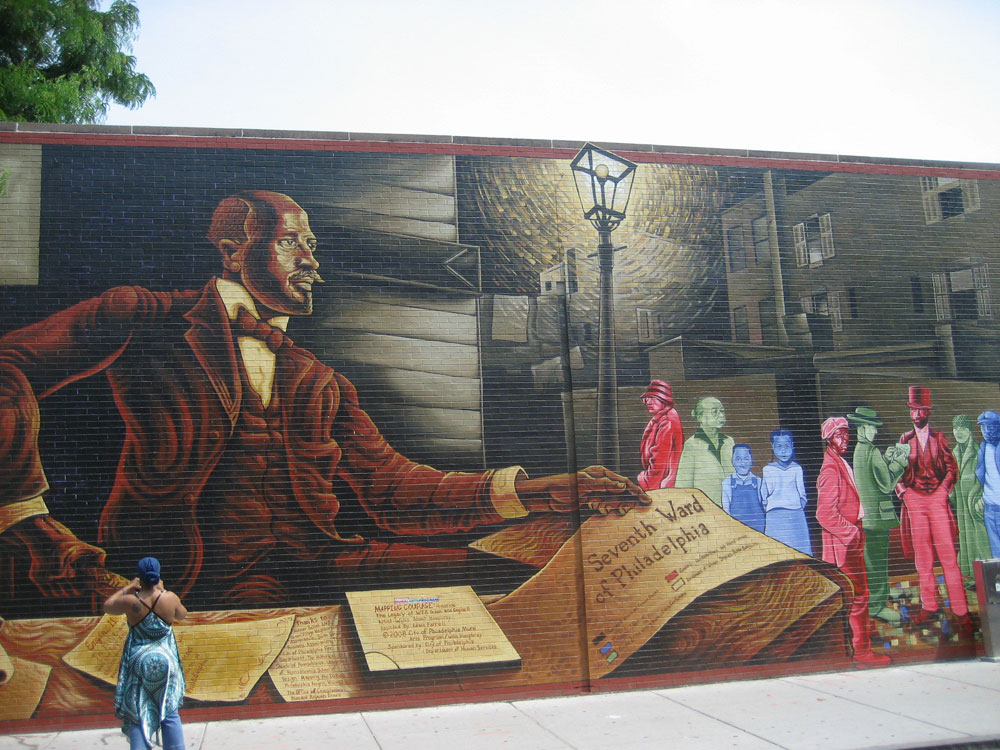

The countervailing forces of belief and doubt remind me of the quote below, which is taken from WEB DuBois’s seminal commentary on 20th Century America, The Souls of Black Folk. Despite being written over 100 years ago in 1903, its relevance today is undeniable. Specifically, the concept of double consciousness perfectly describes a dynamic with which I have grappled routinely throughout my lifetime as a young man from the Midwest coming of age to my professional journey from community organizer to philanthropic leader. It reads as follows:

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness—an American, a Negro…two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife—this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost… He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American…

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

― W.E.B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk

Not surprisingly, in moments where I manage to operate free from any professional constraints or narrow identity constructs, I am aware of an ongoing need to experience myself as whole and powerful—the antidote, perhaps, to the phenomenon of double consciousness. In these fleeting moments, I am open to healing from the dehumanizing impacts of dominant mindsets as well as any cultural norms that exclude, erode trust, reinforce exploitation, marginalize, or perpetuate oppression.

To be completely honest, I have been angry for so long that I have lost count of the years. However, admitting to anger in this way feels risky, invoking destructive stereotypes that engender fear and dehumanize Black males—a secret that throughout my adolescence and early adulthood has robbed me of countless opportunities to learn from my emotions and experience the fullness of my own humanity. Yet only through intentional effort as an adult was I able to develop appreciation for my emotional well-being, including allowing myself to explore beauty, dream, experience awe and disappointment, and cry and recover more able to adapt to change. Only after moving through this process of healing, of unifying any vestiges of “double consciousness,” was I able to experience the emotional realm as a central source of personal power. Only then did I learn how to engage my relationships with grace, curiosity and unconditional acceptance as an expression of self-honor, affirmation, ancestral connection, and gratitude. Only then, when I developed the capacity to “decolonize” my language, beliefs, and behavior, was I capable of experiencing the joy of unfettered self-expression.

Certainly, this way of being is not taught in Western culture and is rarely affirmed. However, adopting a culturally responsive approach to living: engaging my mind, body, and spirit—every aspect of being—is what makes it possible for me to shift from navigation to transformation, surviving to thriving, scarcity to abundance. This involves developing discipline for replacing white supremacist cultural norms with the wisdom, values, and behaviors shaping my ancestral legacy.

In closing, leading while Black has required me to develop a routine of self-reflection to respond effectively to the debilitating impact of double consciousness. By actively integrating the wisdom cultivated through the rich experiences of my cultural lineage, I can effectively counteract the harmful effects of socialization. The timeline for my own personal “decolonizing” journey includes the following milestones:

- It has been exactly a decade since I rejected the construct of race as a political creation used to hoard power and reinforce a false hierarchy of human value.

- It has been a dozen years since I chose to believe that we heal ourselves whenever we create out of rage and commit to promoting racial equity practices.

- It has been a year since I decided to be “all-in” for social change, accepting the role of CEO at GEO [Grantmakers for Effective Organizations] and marshaling the power of my networks to collectively transform philanthropic culture.

We know that no single entity can effectively advance racial equity; it is a collaborative coordinated effort. My experience is that the act of leading while healing is no different!

As a result, I depend on my community of networks to maintain an open heart, mindset, and attitude—the essential conditions for thriving. Likewise, I depend on the transformative impact of racial equity practice as my vocation to generate renewed hope and wellbeing. Most importantly, I have chosen to establish generative relationships with the individuals comprising institutional philanthropy to facilitate meaningful social change.

So far, this journey has shaped me perfectly to respond to the current moment with a clear sense of the prevailing contours of change. Likewise, the process has facilitated my own healing, enlightenment, and personal transformation over the course of a lifetime. If I were to stop now and withhold the best of my contributions, then how would I ever know what type or amount of change is possible? How would I ever satisfy my curiosity for leading change? How would I ever appreciate, truly, the extent to which there is any purpose in struggle?