January 15, 2015; Global Post

In the wake of major government leaders gathering with the UN General Secretary at an international conference in Kuwait pledging to raise $6.5 billion to respond to the Syrian humanitarian crisis, the relevant question is whether the money really gets delivered after all the big announcements. For example, this year’s request for Syria is the largest ever, but last year, only 70 percent of the money pledged by donor nations to Syrian relief actually showed up. Compared to other years and other UN requests, 70 percent is even rather high.

For many readers, a comparable situation closer to home might be whether the donations promised to Haiti in response to the devastating earthquake that hit that impoverished island on January 12, 2010 were realized—and whether they accomplished what they were supposed to. The Global Post asks, “After Haiti’s devastating earthquake, where did the aid money go?”

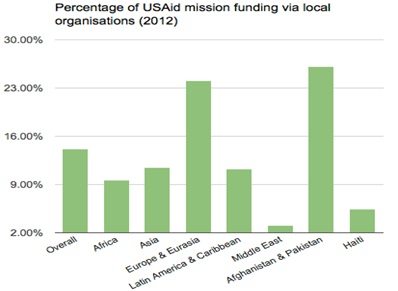

The findings aren’t pretty. Writing for the Global Post, Jacob Kushner says that only 5.4 percent of U.S. government spending in Haiti in fiscal 2012 went to Haitian organizations or companies. The problem appears to be resistance in Congress to reform of USAID practices, particularly in terms of food aid, a topic covered in the NPQ Newswire previously. But there is a particular problem in aid to Haiti. USAID’s global average of funding local groups and companies is 14 percent—still low, but not like the percentage in Haiti. Making it even worse is that aid programs from USAID and international NGOs have long been active in Haiti, but it appears that there has been little success in building successful locally controlled governmental and NGO structures that the U.S. government trusts enough to turn the funds over to them. That keeps Haiti in a position of perpetual dependence on external groups, regardless of the nature and extent of the crises to be addressed.

It’s not like USAID doesn’t know what’s wrong. Tim Padgett, reporting for WLRN, wrote recently that the USAID mission director in Haiti, John Groarke, made it clear to him that “we have to change the way we do business in Haiti.” Partly, he is referring, in Padgett’s words, to “Haiti’s overreliance on foreign support—and its chronic under-reliance on its own ample human and natural capital,” sometimes evidence in the surfeit of nonprofits providing assistance in the country, earning Haiti the sobriquet, “Republic of NGOs.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Padgett suggests that donor nations don’t follow through when they feel that local authorities are not up to the task. He cites the insufficient direction and control provided by the previous Haitian president, René Préval, during the 2010 earthquake and the current questions about the leadership and behavior of his successor, Michel Martelly. The governmental dysfunction and corruption since the election of Martelly don’t give public or private sector donors a sense that their moneys will be well used by local agencies, and consequently they either run the moneys through non-Haitian NGOs or sometimes don’t deliver on the pledges at all.

Philanthropic investments in Haiti, such as the Caracol Industrial Park, developed with funds from USAID, the Inter American Development Bank, and the Clinton Foundation, haven’t quite hit their mark. Caracol was supposed to generate 65,000 jobs, but so far has produced fewer than 1,500, amid charges that garment factories in the industrial part aren’t even meeting the government’s minimum wage requirement of $6.85 an hour, but paying more like $4.56 an hour.

It is odd, however, that members of Congress fret so much about the amount of money going to foreign aid, usually less than one percent of the entire federal budget, when the beneficiaries tend to be, at the outset, for-profit firms inside the Washington Beltway. Typically, around sixty percent of USAID moneys to Haiti goes to and through Beltway for-profit and nonprofit firms. In fiscal 2013, for-profit firms like Chemonics, which got $58 million of USAID’s $270 million for Haiti, were in charge of almost half of USAID funds for Haiti, and U.S.-based nonprofits another 37 percent.

In what part of the world is the percentage of USAID funds distributed through local organizations even lower than the 5.4 percent of funds for Haiti? As this chart from the Guardian demonstrates, it is the Middle East:

That bodes poorly for funds meant to reach people in Syria who are caught between multiple warring factions that include a government that is willing to kill hundreds of thousands of its citizens in order to keep its grasp on the levers of power. Maybe the UN will help generate the level of donations deemed necessary for humanitarian assistance in Syria, but the track record for failing or failed states like Syria isn’t good.—Rick Cohen