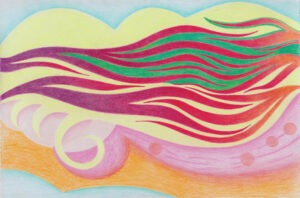

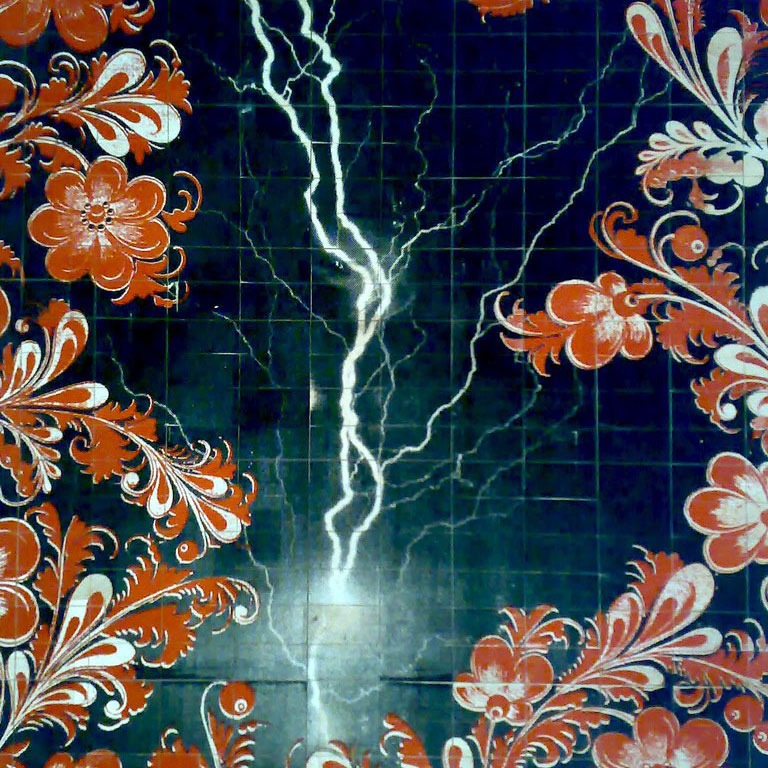

Over the course of days in 2017, the National Immigration Law Center (NILC) went from having 15,000 Twitter followers to nearly 50,000. Their email list quadrupled from 20,000 to 80,000. Soon, their individual donor base went from several hundred supporters to more than 16,000. NILC had filed the first lawsuit against Donald Trump’s Muslim ban1, and they were having what a new report commissioned by the Evelyn & Walter Haas, Jr. Fund calls a “lightning in a bottle” moment. This phenomenon of viral organizational growth is increasingly common as people are activated quickly and urgently by the fast-paced news cycle reverberating over social media. It fundamentally challenges traditional, more measured strategies for base-building and donor cultivation.

Adela de la Torre, who was the communications director at NILC during that explosive surge in attention and support surrounding the Muslim ban, is the lead author of the new report. She explains that the “lightning in a bottle” metaphor is more multifaceted than it appears at first blush.

“We came up with it initially because it really did feel like this out-of-the-blue thing that happened, and we had a following and the funding to really sort of fulfill our wildest dreams.” But as she and her coauthors, consultants Rachel Baker, Robert Bray, and Marjorie Fine, dug deeper into these experiences, she says they realized the bottle was even more important than the lightning. “It’s about the cultures and practices and systems that are in place that allow you to build a bottle strong enough to withstand that lightning moment and then utilize that energy moving forward.”

The report details the growth experiences of two immigrants’ rights organizations, NILC and a grassroots group in southern California called Inland Coalition for Immigrant Justice (ICIJ). The racist, xenophobic discourse and policy that defined the Trump presidency thrust immigrants’ groups further into the limelight. The #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo movements were, of course, also generating participation in unprecedented numbers. What this report lifts up and helps the reader consider is the nature of these viral “lightning in a bottle” moments, characterized by sudden, large-scale influxes to organizations of media attention, digital engagement, and financial support. The tireless activism, organizational, and coalition-building work that makes them possible happens over many years…and then, bam! An event or a policy shift—nearly always of violence or oppression—sets off a massive reaction.

Viral Movement Moments

Last year saw a confluence of such events. The health and economic disparities of the COVID-19 pandemic for Black and Brown communities and the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, to name two significant concurrent forces, set off “lightning in a bottle” moments for racial justice organizations. Mireaya Medina is the data and grants manager at Imagine Black, a grassroots organization that builds political participation and leadership in Portland, Oregon’s Black community. Medina says the organization saw large influxes of energy and support around two of their 2020 campaigns, addressing COVID and policing respectively. Imagine Black, at the time called the Portland African American Leadership Forum, was part of a coalition that successfully advocated for the Oregon Cares Fund, $62,000,000 in cash grants to Black individuals, Black-owned businesses, and Black-led nonprofit organizations that experienced financial adversity due to COVID-19. And in the wake of Floyd’s murder, their “Defund. Reinvest. Protect.” campaign made a series of demands of the Portland City Council to comprehensively reimagine community safety. Now, Medina says, “we are going to be able to grow and expand with a lot of support that we haven’t had before.” This includes adding key staff positions focused on engaging even more people. “We haven’t had a person working full-time on donor development. Now we have a person that’s able to do that. We haven’t had a communications person, and now we do. We have different positions and opportunities that we haven’t had previously. So, we know that in our movement building journey, things are only going to go up from here.”

At ICIJ in southern California, profiled in the new report, executive director Javier Hernandez and his staff were also having a “lightning in a bottle” moment at the intersection of COVID-19 and the carceral state. The group already had a campaign called #ShutdownAdelanto focused on releasing the more than 2,600 people held at Adelanto ICE Processing Center, run by the publicly traded GEO Group—the largest such center in the United States. When the pandemic hit, ICIJ learned that GEO Group used a pesticide called HDQ in its failed attempt to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. According to ICIJ’s contacts inside the center, this resulted in terrible physical impacts and worsening mental health for the people detained. ICIJ organized with angry community members and allied organizations. They posted audio testimonials by people detained on Facebook and Instagram. Media attention grew, and eventually the EPA issued a warning to the GEO Group. Hernandez says that during just this three-month period, ICIJ received over $30,000 in individual donations, far more than the typical volume for this local organizing group. In the end, their individual donations more than doubled from 2019 to 2020 and included their largest gift ever from an individual supporter, $15,000.

And we’ve seen the “lightning in a bottle” phenomenon even more recently with the surge in hate crimes against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) and the murder of six Asian American women in Atlanta. EunSook Lee is the director of the AAPI Civic Engagement Fund, which invests in the growth of AAPI groups as movement and power building leaders. She is still, she says, making sense of all that’s happened since the Atlanta shootings. “The next day we became inundated with emails,” she says. “It was mostly donors who wanted to support in different ways and atypical donors, like corporations who we never had a relationship with before.” But it was also people who wanted to volunteer, and even people who felt unsafe seeking help—needs to which the fund was not really set up to respond. She and her staff were in referral and triage mode, and it was a couple of weeks, she says, before she thought to check their online donation activity. “So, I contacted our fiscal sponsor to check what money had come in. And I saw that we got about 20,000 dollars in the first day. And in a week, about $50,000 from over 500 people.” This was very unusual: individual, small gift support for a funding intermediary. Lee says they did not even have a donor database or a standard thank-you letter. The increased support meant they could get larger grants to groups on the ground combatting hate and nurturing AAPI civic engagement. In May, the fund distributed $6.5 million to 30 local AAPI organizations in 17 states across the country.

Activating a Bigger, Broader Constituency

One of the most complex aspects of leveraging a viral moment is how substantially an organization’s constituency can change not just in size but in composition, sometimes literally overnight. Bethany Maki is managing director at Progressive Multiplier, which provides funding and capacity building to progressive organizations to build sustainable financial models. “A lot of these headline-driven fundraising moments will get to donors who are nothing like your core supporters,” she says, “because you have a new awareness among a population that wasn’t aware before. That in and of itself creates its own tensions.” She advises groups to consider whether they will proceed with fundraising in the moment, knowing that many new donors will be “one and done,” or whether the intention is to build out strategies for retaining this broader group of supporters who may bring different understandings of and proximities to your issue.

For NILC, the choice was decidedly the latter, and it meant substantial changes to how they communicated with their expanded base. The new report even includes a side-by-side, before-and-after of actual emails NILC used to engage their supporters. NILC staff worked with consultants and studied data like open rates and click rates to see what resonated.

“The biggest change for NILC,” the authors write, “is that its brand identity and outreach have undergone a paradigm shift—from an organization focused on acting as a legal interpreter for its audience toward one that mobilizes and engages everyday individuals to participate in advocating for a more inclusive immigration system.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Imagine Black in Oregon is experimenting with ways to incorporate and engage their newer Indigenous, people of color, and white supporters without in any way decentering the Black Portland community for whom the organization exists. They created an Accomplice Monthly Sustainers program as a distinct complement to their Kinfolk Members program. In their website invitation to become an Accomplice Monthly Sustainer, they explain, “As you learn more about Imagine Black, you will find a clear opportunity to become more than just an ally, but rather to be active accomplices with the Black community in the shared struggle for liberation for all.”

Preparation & Experimentation

It may seem oxymoronic to prepare to catch lightning in a bottle. But, when you listen to the stories of staff who have been through this, you do hear common themes. Again, as the report’s lead author de la Torre said, “it’s really about the bottle,” meaning that what transpires from these moments of heightened attention depends upon the organization itself: its clarity of purpose, its staff and leadership, its commitment to engaging constituents and allies, and its culture.

Perhaps the most important way to prepare for periods of viral growth, the authors argue, is to nurture a culture of agility and experimentation. Hernandez and the staff at ICIJ embodied this as Trump’s draconian immigration polices chaotically unfurled. This campaign in 2018, when Trump had walked back the “zero tolerance” detention efforts and border agents were dropping immigrants at bus stations across the Southwest, captures their creativity and responsiveness:

In response, ICIJ activated networks on social media and elsewhere to raise small sums of money to enable immigrants to continue their journey to their final destinations with dignity. Hernandez and his team used technologies like Venmo and SMS to enable giving rather than pushing everyone through a centralized, web-based donation site.… During an interview on Spanish-language radio, Hernandez invited listeners to text “apoyo” to a number to help out, eliciting contributions from listeners around the country. [He] estimates that ICIJ raised over $15,000 on Venmo and $20,000 on GoFundMe over the two-week period.

Today, Hernandez says, ICIJ has 20,000 text message subscribers, and he and the team are working to figure out how to convert even 1,000 of them to dues-paying members to ensure the long-term sustainability for their work.

Bethany Maki from Progressive Multiplier draws parallels between traditional natural disaster fundraising and readiness for viral movement-building growth: “Literally at the beginning of hurricane season or typhoon season, we would have assets ready to go because we knew the storm was coming and there would be an opportunity to fundraise and to bring people into the cause. We didn’t know when or where, but we knew it was inevitable.” She says it’s about applying some of those same readiness tactics in progressive nonprofits that are now getting many more news-driven opportunities. What is different in movement building are the complex strategic choices leaders have to make about which events to respond to and how. Maki advises having those conversations on a rolling basis so that leadership, communications, fundraising, and mobilization efforts are on the same page. “There is a little bit of extra planning so you can move quickly. That is the linchpin piece—making sure you have the conversations in the organization. If this court decision comes down, or this news story breaks that we’re hearing about, or whatever the moment might be, are we okay fundraising off of it? Who are we going to target? So that we have an open highway to run in. Those kinds of conversations are best had before it happens. It’s really adding in those elements of agility preparation onto an already good, solid engine.”

Essential Infrastructure for the Long Game

When we widen out from individual organizational capacities to consider what social justice movements writ large require to achieve viral growth, we have to factor in the relevance and agility of the infrastructure, too. Among them are groups like the aforementioned AAPI Civic Engagement Fund, or Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Asian Law Caucus, who, their executive director Aarti Kohli says, pivoted quickly as AAPI hate crimes escalated and convened a table of more than 100 grassroots organizations to strategize and respond. Kohli’s concerned that as the viral moment passes, AAPI organizations will still confront a “lack of resources to help build infrastructure.” She cites a recent AAPIP study that found only 0.2 percent of foundation support is designated for AAPI communities.

Or consider the reproductive justice movement, which is steeling itself for yet another “lightning in a bottle” moment with the Supreme Court’s decision to hear Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Quanita Toffie is senior director at the Groundswell Fund, the largest funder of the reproductive justice movement in the US. Beyond grantmaking, Toffie and her colleagues provide intensive capacity building to grassroots organizations, including those adding 501c4s to engage in electoral advocacy. Toffie says that for groups closest to community, for BIPOC-led organizations that have gotten us to this point where, as she puts it, “change feels so much closer in reach than ever before,” investment and capacity building led by people who themselves have worked in community is absolutely essential. “We know [social justice] work can only be moved when relationships exist with organizations on the ground doing the work and [when there’s an] understanding of what it takes to actually invest in the long-term infrastructure that is needed rather than the one-off, sort of boom-and-bust cycle that a lot of funding tends to go in.”

So, the paradox is that viral growth actually requires committed preparation. This new report’s case studies and useful “Putting it into Practice” addendum now themselves become a part of the infrastructure—resources for staff working across movements for social change who want to, as de la Torre says, “build a bottle strong enough to withstand that lightning moment and then utilize that energy moving forward.”

Notes

- The lawsuit was filed in partnership with the ACLU, the International Refugee Assistance Project, and Yale Law School. Learn more here.