Editors’ note: This article is from NPQ’s spring 2023 issue, “The Space Beyond: Building the Way.” In this conversation with Cyndi Suarez, NPQ’s president and editor in chief, and Marcus Walton, president and CEO of Grantmakers for Effective Organizations, the two leaders discuss NPQ’s and GEO’s journeys of organizational transformation, and how we move beyond the what is to embrace the what can be.

Marcus Walton: I’m proud of the progress you’ve made.

I remember this [NPQ elevating the voices of social change leaders of color] was a vision of yours. And it took a lot of courage for you to move NPQ in this direction. I just remember the earliest days, and I’m so excited to see you doing it. You are making such an impact in the field in ways that I just couldn’t even imagine.

Cyndi Suarez: Really? What are you seeing in the field?

MW: I feel like you’re giving space for creative people to produce valuable assets, to practice exercising our voices; and in doing so, the platform is giving credibility to an entire group of people for whom the sector didn’t provide the same kind of entrée. I mean, creatives were able to achieve a certain level of visibility prior to NPQ, but it took initiative to establish it. Now, you can kind of cheat, you know . . . funders can simply look at NPQ’s growing body of work and see who you’re talking to.

CS: It’s true. But you know what? Those people have also given NPQ credibility.

MW: Well, you already had it, as far as I’m concerned. That is something that I just haven’t thought about. It was a “given” to me—but yes, you’re absolutely right.

CS: That’s interesting, because it’s had a certain kind of credibility, but I think it has a different kind of credibility now.

“We’re being asked to do so many things that the sector needs. But I’m not sure we should do it all. We need to partner with people and create an ecosystem, so that we can do a part of it and then other people can do part of it.”

MW: I agree with that. It’s just, to me, through this platform, you are really showing people what’s possible through reimagining our world. But you’ve always had the vision. It’s just another way. Now there’s a little bit more access to resources available for everyone to share and experience. Relationships are just more open. Platforms like NPQ make the search easier.

CS: I have so much fun in my job.

We’re being asked to do so many things that the sector needs. But I’m not sure we should do it all. We need to partner with people and create an ecosystem, so that we can do a part of it and then other people can do part of it.

MW: I think that’s the best contribution that we [GEO] can make—that we are a community and have infrastructure. I want that infrastructure to go toward spreading this story and hosting these conversations, so it’s not just you and me, it’s you plus the next leader in a particular area—to help us all understand: What does leadership look like in this space? What does effectiveness look like in practice, in this context? And then for all of the leaders we see you interviewing, we can routinely interview them every few months, or have them as a part of our ongoing webinar series around whatever it is that you label it. But GEO can be one of multiple venues for you to bring that content to life in a different way.

So, for example, the Maurice Mitchell story, which caught fire in 2022—best story of the year.1

CS: It really was. It was our most popular story.

MW: It was, because everyone’s been struggling with the challenge of building resilient organizations; especially throughout the pandemic as well as this unprecedented period of global racial awakening and reckoning, which I believe is still underway!

CS: Right. Right.

MW: And so, I want to position that for funders, for people who are leading philanthropic organizations, to be able to think differently and workshop ideas for integration with peers, and grapple constructively with the myriad complexities associated with implementing racially equitable principles and practices. That article can be a yearlong exploration.

CS: He wants to do that.

MW: That’s what I want to do.

CS: Yeah, let’s do it.

I’ve known Moe forever, and I’ve never seen Moe not be amazing. I’ve never seen him not change everything from a place of utter humility and competence. You know what I mean? He’s just one of those people.

MW: Think about how we can bring that alive as workshop experiences for people over the course of three years, five years. GEO’s a dynamic community as well as an evergreen institution. We don’t have to think in just these tiny little buckets of time. I want to stretch this stuff out and make people feel like they are part of a journey, an experience that matches the progression of their careers. Let’s hear about how we arrived here, and really challenge people to think in their seats—how these things are playing out in practice. Part of what the field needs is for our workplaces to be characterized by presence and expansiveness—spaciousness—which are essential for creatively responding to issues that we’ve never seen come forward in the same way before. Right?

My highest aspiration is for GEO to be a space where leaders-of-color issues become mainstream. We’re intentionally mainstreaming issues that were previously considered fringe. We want them to just be normalized. Like, No, you don’t have to be scared of this anymore. It’s just what it is. Our fates and futures are shared, not separate. Let’s work together toward a shared vision for thriving.

CS: I wanted to ask you about that. Because I had the pleasure of going to the GEO conference last year, and I see the difference. I was like, Marcus is doing something over here. And I knew you were, but I think that was the first time I saw it.

“A thesis that guides all of this is that the work of enduring leading change is relational, and it extends beyond our positions as well as our organizational affiliations—its impact is deeply personal.”

MW: It was the first evidence through an in-person experience that anyone could really grasp. However, the journey started before my tenure. Hiring me was a realization of one feature of GEO’s commitment to racial equity as a community, which was declared publicly at the National Conference in 2018, in San Francisco.

CS: Right, right. I mean, I’ve been to GEO conferences before, and they never looked like that. So, I wanted to hear about that and to hear about what you’ve been doing. I mean, it’s my third year at NPQ, and this is your third year, too, right? So, what’s it been like? What are you learning?

MW: I’m gonna give you the unfiltered story—from my point of view, of course—to clarify the record and honor so many leaders over the past decade or so (and beyond) who don’t get credited with their contributions to GEO’s transformation. I know that’s always welcome with you! Let me say first and foremost, a thesis that guides all of this is that the work of enduring leading change is relational, and it extends beyond our positions as well as our organizational affiliations—its impact is deeply personal. For example, my relationship with you is evidence of that. And any progress is a result of our commitment to supporting each other’s aspirational vision over time.

CS: I think that’s a very Marcus approach. That is very you, Marcus. Not everyone does it that way.

MW: Okay, perhaps so.

CS: What brought you to that? Maybe you’ve always been like this—just like I’ve always been kind of bold; I just now started getting rewarded for it.

MW: Yeah. I can’t say I’ve always been like this. In some ways, I am motivated by winning, Cyndi—I simply want to win. But I want everyone to win, not just me. And so, if I come across a situation where someone has been effective in their pursuits, whether I agree with their politics or not, I say, “You know what? That approach is effective.” And boom! I latch onto it and integrate it into my evolving set of approaches and ideas for advancing my pursuits. Over the course of time, I’ve met many people from different backgrounds, and I’ve learned the most from those who challenge my way of being and thinking—mainly, ordinary folks who are patient, loving, and generous with their care and insights. To this day, I admire those qualities in others. And I appreciate how the practice of acknowledging the people who I admire checks ego and keeps me flexible, open-minded, and open-hearted. I find it profoundly humbling!

As I developed a habit of patterning certain aspects of myself after people who made lasting impressions on me, eventually I was able to be effective in similar ways. So, I just kept doing it. I experienced it like this: “Oh, that worked! What if I try that here? Oh, what if I read The Power Manual and follow the point of view that Cyndi put forward?2 This stuff works!” And so, to this day, I just keep going with it. And it has shaped me to the point that now I talk about the importance of allowing the change process to transform me or to transform us as leaders. Being “all-in” does that. As a result, I have experienced personal transformation many times throughout my career. I’ve been the beneficiary of growth, if you will, from patterning myself after people I admire, who I think are brilliant, who I think just offer something that is special. And in some ways, it just rubs off. I’m not saying I’m special, but I am confident that the characteristics of the people with whom I surround myself express themselves through how I show up as a leader.

CS: Yeah, I think of that as channeling. I’ve been in situations where . . . you know, I used to have a little bit of a bad temper. I’m still, you know, fiery.

MW: Yeah, I like it though! The provocateur!

CS: I’ve been in situations where I’m like, I’m gonna channel. This is not the time for that, and I’m gonna channel this person. It just happens. I end up being real patient and real sweet and all this stuff, so I get it.

So, tell me a little bit about your journey at GEO.

MW: My journey of organizational transformation at GEO is so interesting. For different reasons, I’ve been invited to tell this story a few times this week! And I don’t believe in coincidences, so I’m inclined to believe it’s time. So, year one, I came into an organization with a history of bringing people together, of highlighting important work in the sector and taking stances in support of nonprofit grantees and communities, but not necessarily focusing on mobilization.

The leadership transition of the founder had a profound impact on staff, as leadership transitions do, impacting the organization in a manner that required leadership to prioritize supporting the healing and a kind of reorientation of the organization. Cyndi, like so many other scenarios in our sector—as evidenced by the building resilient organizations article—GEO experienced organizational tensions that were bubbling beneath the surface, including staff wanting to push change faster around racial equity, and having different appetites for change in other areas of operations and programming. Over time, every person was impacted, and the mood was uneasy at moments. In my opinion, overlapping cycles of attrition in key positions took an emotional toll that required us to work together as both staff and board. As folks matriculated out and those roles weren’t immediately filled, a kind of structural degradation started to occur inside of the entity.

CS: And how big was GEO at the time, in terms of staff?

MW: It’s back to its original size of around 24 or 25 folks.

CS: And what level of attrition had it reached by the time you got there?

MW: It was 14 or 15, but the combined impact of sheltering in place/the pandemic, racial reckoning, and political unrest made it feasible to imagine additional staff turnover.

CS: And was it mostly people of color who were leaving?

MW: Oh, no. There was not a large percentage of people of color working here.

CS: Really? So, White staff were also leaving?

MW: It felt to me like a more accurate way to characterize the trend was around years of experience. A critical mass of senior officers transitioned out of the organization as I was transitioning into my role. So, folks who were new to the field, or new to leadership, were being challenged around the kind of support they needed in the absence of senior leadership who had significant experience with GEO systems and processes, as well as a working understanding of how things function within the philanthropic sector—whether it’s written or unwritten rules, right? These were the dynamics playing out. There were people of color representing a variety of ethnic and cultural backgrounds—from South Asian to African American. But there wasn’t ever a large number of any particular group. So, it resembled a diverse workplace in the traditional sense, in that it was majority White-identified staff.

CS: So, it was the leadership that was leaving?

“When I came on board, people were looking backward and feeling the effects of exposure to persistent disruptive forces of organizational change. They needed additional therapeutic space to sort through the impacts of this experience, acknowledge it all, and say, ‘Yep, this happened.’”

MW: As it sometimes happens within small-to-medium-size organizations, a critical mass of officers in core areas of the organization left in succession. And that level of attrition happening in overlapping variables had the obvious impact that you would expect on GEO. So, I came in first having to address that and then having to simultaneously support the individuals, because they were vulnerable. Folks needed and wanted guidance. But the disruptive nature of the leadership transitions generated distrust—despite noteworthy attempts of leadership, who continued to steward the organization throughout every phase. So, there was the twofold challenge of stabilizing the organization and supporting the individuals through a collective grief process, because they had experienced a lot of loss as well as a lot of transition in a small amount of time. That was 2019, September.

CS: How did you address that? What did you do?

MW: It was a systematic approach, which involved shared leadership. As a complement to the skills and experience of the remaining senior leaders on the team, I brought a coaching and racial-equity training background from which I could draw: ontological learning. And so, I knew, Okay, there are some ways in which we can help people acknowledge what they’ve been through, derive any value from the experience, then release it. But it’s a process that one has to go through. You kind of find emotional acceptance with things, and then start to reorient your focus toward what you want to experience next. When I came on board, people were looking backward and feeling the effects of exposure to persistent disruptive forces of organizational change. They needed additional therapeutic space to sort through the impacts of this experience, acknowledge it all, and say, “Yep, this happened. There’s nothing wrong with you. This thing happened. It’s not your fault.”

So, the team and I had to be really creative about how we did that, because we simultaneously needed to build trust with each other as senior leaders and with our colleagues within the organization. No one could do this alone! Now, interestingly enough, Cyndi, September/October 2019 is just six months before the pandemic, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd. Around this time, I was doing one-on-one informational interviews with staff, with previous board members, with existing board members, and with potential partners—including exploration with Equity in the Center as an institutional partnership. Then, the world changed all at once! So, we were challenged to respond to the needs that were particular to the pandemic while still being in stabilization mode from the leadership transitions. Like everyone, we moved to remote status; yet we still needed to fill some critical positions that had been left vacant for long periods. After considerable deliberation with GEO leaders, as well as with leaders within the ecosystem of change-focused organizations, I decided to bring in resources that responded to organization-wide patterns and trends that threatened to erode trust and weaken the social fabric among the staff and board.

CS: Can you give an example?

MW: Yes, one example was that there were people at different stages of the hierarchy, different levels, who were saying, “My experience of GEO is this”—so, let’s say that’s the associate level—and then there’s a middle level of directors and managers who would say, “Well, mine is like this.” It would be similar but slightly different. Some things are common, some not. And the senior leadership might be feeling an entirely different thing, because of their responsibilities as well as the time of tenure or vantage point of the philanthropic landscape. Because, people had seen or experienced certain cycles before, and it didn’t generate the same response for everyone within the organization or broader community.

CS: That would be me. I’ve been through like, five or six of these organizational transitions.

MW: But some differences in response were being interpreted as lack of care. What do you call it when you simply are not paying attention to certain dynamics within a situation or relationship?

CS: I know what you’re talking about. Not abandonment, but neglect.

MW: Neglect. And the feeling was abandonment. And people in different places within the organization were feeling like, Our culture is one of neglect, and I feel abandoned. This is inside of the very organization that I continue to lead today! So, I’m saying, Whoa!

“‘Everyone has a role in supporting the transformation of society, and it starts with an individual focus of our personal transformation. And the nonprofit sector has a critical leadership role in this.’”

CS: What was it like for you?

MW: It felt horrible. If it weren’t for the network of folks who were supporting me prior to coming into GEO— plus during—then I don’t know what I would have done. Certainly, my experience would’ve been different. Luckily, I had the foresight to know that if I was gonna do this, it had to be through shared leadership—that I had to be leaning on my colleagues both inside of GEO as well as in the field for support. And I did. I wasn’t foolish enough to believe like, Oh, I’m so this or that, and I got this. Instead, I was like, No, I think I can . . . I think I can do it . . . and I want to ask for help from all of these different people to support me through it. And they did, in different ways. And one of the hallmarks was the article around double consciousness that you invited me to write.3 It caught fire. It was so viral in so many important spaces, that it captured the attention of folks in the ecosystem. It provided valuable visibility to the point where when I knocked on a door to cultivate a new relationship, people were interested and already motivated to open it. What was it about the article?

What do you think they were hearing that they needed to hear? That I don’t know. I am very uncomfortable speaking from someone else’s point of view. But what I do know is that there was so much energy generated from that writing.

So, I feel like it was from that moment that I started to enjoy a professional reputation for being circumspect, for being inclusive, for still representing at its core the need to address inequity, address all of the isms, prioritize communities that are disproportionately impacted over time historically—including and especially Black ones, but with an intersectional emphasis. But I was saying, “We are all in this together. Everyone has a role in supporting the transformation of society, and it starts with an individual focus of our personal transformation. And the nonprofit sector has a critical leadership role in this.” So, you gave me the platform.

CS: Is that, for you, the gist of your article?

MW: No, no, no, but just the way you asked the question of double consciousness in the article—including, “What’s your experience as a Black leader today?” It was so unfiltered . . . so raw . . . relevant to the Black experience in today’s context, which was unusual at the time! And when my response was one that invited everyone—i.e., the cultural diaspora—into it, it set an important precedent of, like, Oh, that’s how he rolls. It allowed me to honor my experience as well as my point of view, unapologetically.

CS: It’s very interesting, because I get that, too, from my book. I’ve had a lot of White men from all over the world tell me that it’s a generous book. They use that word—and I say, “Why do you use that word?” They say, “Well, you’re not trying to shift things so that Black people are on top; you’re trying to change it for all of us.” And I’m thinking, That’s White people’s biggest fear.

MW: I have been a part of many conversations discussing that as a common point of fear, Cyndi.

CS: That we’re gonna do to them what they have been doing to us.

MW: What “they” did to us. So, check this out! One of the conversations that came out of that was a colleague—who wasn’t a colleague back then—sharing how she believes one of the biggest challenges of racial equity work is that we’re asking people to be in relationship professionally in ways that are more intimate than their personal lives. The fact is, some of us have never focused on vulnerability and trust to this degree before. So now, think about how that insight informs what is truly needed in our civic engagement efforts. That’s how it connects back to GEO. We understand that what’s needed includes a welcoming space where we support people through that reorientation, that development of a process in which they’re challenging their own thoughts, they’re feeling insecure (“What about my identity?”), the whole breakdown that goes with that—so that we can build it back up.

“The goal is not racial-equity analysis. That’s just the analysis, right? The end goal is that we are able to consider thriving from a position that is devoid of restrictive, historically based constructs that are all about power and manipulation. Instead, it’s about humanity.”

I have done that in my coaching practice. I have a familiarity with how that cycle works. And so, that was the approach I used. And then, externally, starting to reorient our programming to situate people in that point of view—of shared leadership as well as all being in this together. So, think back now to the national conference, and some of the conversations that you experienced. We’re on a particular message: we’re saying that equity matters, racial equity matters, for effectiveness. And that was a message that was first announced back at the 2018 National Conference in San Francisco. But now we’re also inviting you into a process to grapple with complexity, because it’s everyone’s issue. This is not exclusively a Black people issue. This ain’t a “of color issue.” This is not a White-identified issue. These constructs do not serve us outside of data generation and analytical efforts. Instead, we are all implicated in this as a multicultural, pluralistic society. And so, that’s GEO at its best—my vision is that GEO becomes a place where we get better and better at having these conversations across difference.

CS: Yes, it’s really interesting, because I think about NPQ, and now we are definitely a people-of-color organization. It wasn’t intended. It was just that when I was looking for people who knew the complexity of the issues, those are the people who did. So now, Joel, my copresident, who is a White man, I’ve honestly been just so impressed and amazed by how he’s become such a great partner in this work.

MW: That’s so good.

CS: NPQ went through a really similar transition.

MW: So, here’s the thing, and I’m gonna give you credit for this—again, this is a shout-out to NPQ. The evolution of that story that I started with, and that story that I was telling you about GEO? Today, when I take us forward into a vision of living beyond constructs, that’s the end goal. The goal is not racial-equity analysis. That’s just the analysis, right? The end goal is that we are able to consider thriving from a position that is devoid of restrictive, historically based constructs that are all about power and manipulation. Instead, it’s about humanity. It’s our common humanity that guides our work. It’s the most antiracist posture that has occurred to me so far.

“I thought, There has to be a way for us to have these discussions where people can have integrity, where people can actually be human. And I think that’s the generative stance—that’s why I started to move beyond race to talking about power.”

CS: Totally. It is about humanity. And when I wrote my book, actually, that’s what I had in mind. After being through so many organizational change processes, I said to myself, There has to be a way for us to talk about this. Because I had done so many years of training to develop my capacity in power work, and I thought, No one’s gonna do this. This is too high of a bar.

MW: Oh, I know. Like, are you kidding?

CS: Like, how many years studying this? And I thought, There has to be a way for us to have these discussions where people can have integrity, where people can actually be human. And I think that’s the generative stance—that’s why I started to move beyond race to talking about power.

MW: And so, check this out, though. In order to do what you just said, it occurs to me that we have to, as individuals, do our work. Like, I had to do my work. I had to heal, or else I was gonna be triggered by whatever that person over there does. I learned that if I still harbor unexpressed emotions about what happened in the past—to me or my grandparents or other ancestors—and I haven’t reckoned with its impact on me and released any residual contempt to liberate myself to dream about and reimagine what’s possible now, then it’s only going to contribute to toxicity in me and my relationships, by extension. And so, that’s what I’m bringing to GEO: a vision for fostering healing, reconciliation, and thriving together. And moving capital into places where it is most catalytic for change is an essential part of the process.

CS: I always think if I didn’t have a spiritual practice, there’s so much that I would not be able to do. It’s funny, because in the piece I wrote for this issue, “Leadership Is Voice,” Foucault starts talking at the end about Socrates.4 Apparently, Socrates was considered a realized being. He’s considered a siddha.5 And at the end, where Foucault talks about practices, he talks about how, ultimately, they are spiritual— he calls it the technique of techniques. He says they’re all ultimately spiritual practices around self- sovereignty around your thoughts, around your actions, and around how you live your life.6 So, when I think about these things, they’re such high bars. I mean, just like the other thing is a high bar, right?

When I think about it now, when I sit in the spaces for people of color who are struggling—spaces that are hosted by funders—we don’t get to this. We stay in the material realm. Because going there requires a higher level of consciousness, and I feel like we don’t talk about how that’s a prerequisite for the work.

MW: I love being able to slow you down. I love your pace, and I love breaking your pace down into its components. But I think this is what GEO can be to NPQ—that’s why I said a five-year plan. That’s how long it takes to start to internalize some of the stuff that we’re talking about. So, check this out: What if we consider that consciousness itself is a leadership variable? Yes! This makes it possible to make different connections to what it means or what is required to be effective as a leader. In this context, I can now consider the possibility of spirituality (i.e., the practice of cultivating consciousness) as an antidote to colonialism or White dominant culture. Some may say, “Why is that? How could that possibly be true?” Because if you catalogue the myriad expressions of dominant cultural norms and values, the headline is a prescriptive list of regimented rules that dictate value and superiority, right? Whereas spirituality is the opposite. It says, “Hey, there’s more than one way. But there’s a common path.” And my experience is that it moves in a direction of that self-realization that you talked about, of self-actualization. It honors our collective humanity, and it moves us toward a shared vision of something that is bigger than our individual pieces and components. That, to me, is the biggest, most oppositional force to any dominant or competitive way of being—the way that says, “Comply, comply, comply. Be this way, or you’re not valuable.”

CS: Now, there’s so much in that, Marcus. So, I have a whole section on this in my book, where I talk about the tattvas7—because my spiritual practice is Eastern based. The tattvas are about 36 levels of reality. The highest level is unity consciousness. And then, as soon as you start dropping down, I think at the third level, you start inserting difference. Difference is the thing that ignites power dynamics. As soon as we start to see each other as different, we get separation. And power starts coming into play.

MW: That’s right. That’s what Dr. john powell is talking about with othering and belonging.8

CS: Totally, totally. It’s really hard for people. But then there’s also the thing about abundance versus scarcity. The highest level is also the level where you already have everything. And so, once we have those two things . . . like, whenever I have an issue, I sit down and meditate. I meditate and do yoga every day, but if I didn’t have those kinds of practices to anchor me . . .

MW: That’s the answer to your question, Cyndi. You started asking me how I did this at GEO. It’s because I had that spiritual practice. I had that foundation. I just called it coaching because I needed a secular modality that wasn’t stigmatized. It’s always been a practice of cultivating and expanding human consciousness.

CS: Can you say more? How are coaching and spiritual practice similar to you?

MW: Ontological learning, which is the version of coaching that I offer, deals with three realms of being. It’s the science of being. We look at the language realm, the emotional realm, and the somatic realm, and how they overlap, intersect, or not. And places of intersection represent coherence. It’s harmony. It’s oneness. It’s alignment. It’s being centered. And so, you’re saying things, your language reflects your actions, and your actions and language also reflect your mood and emotional state.

CS: This is what Foucault talks about in his book. He says that, ultimately, the truth-teller is the one for whom there is no gap between the logos and the bios—what you know and how you behave. And it’s really interesting, because in Vedic scriptures, that’s called “Matrika Shakti,” the power of words.9 Words create the world. And to me, as a writer . . . that’s my mantra.

MW: Your jam. It’s where you live.

“You have to be careful about the thoughts that come into your mind, and which ones are yours and which one are not. Which ones align with what you’ve chosen as important and which ones do not. So, I think about that a lot. And this is why I’m so into leadership as voice, because I know that our words create reality.”

CS: And so, when I came into this role, I started to think of it as articulation leadership. And what I tried to have writers focus on is saying what needs to be said that is not said. And to say it in the way that is the most abundant.

MW: That’s an important element: the most abundant way of doing it. It’s not always what people choose.

CS: Oh, no, no, no. And I have to—I always—think about this. So, Matrika Shakti. When I first started, I had a lot of people ask me: “Are you overwhelmed?” It was almost like they wanted me to be overwhelmed. I’m like, I am not using that word. I would say: “No, I am learning to live in abundance.” Because I knew that if I started to take those words on. This is where the sovereignty piece comes in.

You have to be careful about the thoughts that come into your mind, and which ones are yours and which ones are not. Which ones align with what you’ve chosen as important and which ones do not. So, I think about that a lot. And this is why I’m so into leadership as voice, because I know that our words create reality. Words have so much power—and by the time you utter them, that is when they have the least power. The most power is when it’s still in your gut and you’re still forming it, and you’re still trying to figure out the word to capture the big thing that, even when it comes out as a word, it’s already . . .

MW: It’s already distilled down so much. But here’s the beauty of what you just said: We say we live in language, in ontological spaces. But what you just described and what I know through practice is that in order for the abundance mindset to be possible, I had to get to a point where I believed that life was always responding to my deepest desire through experiences. So, it was creating physical experiences for me to engage and learn lessons. See things play out. That’s what you just described. It’s not the words. The words have creative power, too, but it’s the form. It’s as the words are being formed internally and moving through the energy centers. That’s where, through the meditative practice or the breathing practice, I’m connecting into what it is that is driving me. What’s the root cause of my thoughts and behavior? What is my language when I, as an observer, listen to the way I’m organizing words? What is that telling me? What narrative is informing my beliefs? That’s what coaching, in the way that I have described it to you, has helped people do: to be intentional about understanding how those things are working together or not, and then shift into a posture that is more aligned.

CS: Same, yeah.

Can you tell me a story about when you saw this all come together at GEO? Is there something that captures that? Because what you’re saying, it’s almost like . . . I get it, but it can also be ephemeral. And I’m sure people are going to be reading this and being like, Well, how did he do that?

MW: It hasn’t completed. The cycle is not complete yet. And so, I have gone through the stages of laying the groundwork for this. And it has transformed me as a result. The most important element of this is that I’m not doing GEO any favors, GEO is doing me a favor. By joining the leadership of this entity and this group of people that represent the GEO community, the process of transformation has transformed me, Cyndi.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

I have had to adjust. I came in with a vision and language and a way to do it. It’s like, Oh, yeah, I can see a plan. It was an 18-month plan. And if we take these steps, we can arrive at this way, this state. And then real life happened, and I had to scrap that thing. And when I threw it out, it opened me up. And when I opened up, I had to listen. So, when the staff that was creating—perhaps was perceived as creating—this tension, or pushing the hardest, advocating for things . . . I listened. I heard them differently, because I was open. And then I would go back to the lab, and it would inspire an idea. And I would take that—I would socialize that idea among the group, and we would iterate. So, the process has been an iterative one by which I could still maintain the synthesis from all of the one-on-ones. I can use the synthesis to be informed by what I was learning through the ongoing adaptation.

CS: You’re like a vessel.

MW: Yeah. But constantly either being a barometer or a thermometer, as Dr. King would say. Checking the pulse, the temperature, checking the pressure, but also adjusting it. And doing so in partnership. It’s all in relationship, because we have to move together. That’s the other important lesson, Cyndi. The reason why we’re not there yet—and maybe we never get there, as we talk about spiritual practice—maybe the reason we never get there is because we’re always meeting people where they are. And so, I’m scanning the group to see who is an outlier, and making sure they feel connected. What do we need to do to make sure they feel seen, held, and heard? And that requires an action. So, I can’t move ahead too fast without making sure that everyone else is coming along, feeling heard. Am I moving too fast to where I didn’t hear someone? Let me double-check. So, now I’m circling back. And I’m checking in with everyone to see, What has become clearer to you through the process that we haven’t addressed so far? So, that is how we are moving. And that is creating a different kind of credibility for GEO.

The unfortunate part is that so much of this organizational alignment work goes unseen by external audiences. I made a commitment in 2020 to use the time—when the pandemic shut everything down—to focus on our internal workforce culture, to spend the time and resources to build relationships, to support individual progress and growth, so that we can then get to the external work. And at the time, I was expecting, like, Oh, this will just be a year or so. But we spent that time. I made that investment. Along the way, we got the MacKenzie Scott grant. So, I had some additional capital resources, much of which are directed into really transforming spaces, bringing in consultants to make sure we have organizational alignment (for example, Sheryl Petty‘s work).10 To make sure that we were looking at the relationship among folks on a senior leadership level, director level, different levels within the organization . . . making sure that compensation was following an equitable process. All of that is what the staff of GEO have done in service of the GEO community. Why is that important? Because, prior to this, GEO didn’t maintain an explicit body of work around racial equity. We weren’t expert in it. But now we’ve accrued meaningful experience, and we develop more each day. Now we can tell you firsthand what equitable operations can look like in practice, because we do it—so far, we’ve changed more than 30 policies around HR.

CS: Like what?

MW: I’ve got a running list of the things right here that I read on a regular basis. So, yeah, one of them, for example, is reframing sick leave to wellness leave, and making sure that the team members use leave time to support their wellbeing in a more generative and broad way. So, the definitions were loosened.

CS: You don’t have to be sick to take time off.

MW: Yeah. We increased the monthly transportation benefit to $100 a month, and added parking to that. And that’s just based upon feedback from the team. We eliminated the year-end rollover process for leave, to where now you can accumulate leave over time. Because people were being penalized for not taking time off within the more restrictive space of a year. We said, “What if we go two or three years?” We just consider that in our calculator. And there are so many of these things. We eliminated a 30-day waiting period for new hires to enroll in healthcare—stuff like that. Those are equitable practices. The newest folks in the game can generate the same benefits as the people who have been on staff the longest. So, we just systematically have done so. And these are just the 1, 2, 3, 10, 15 things that I keep on my desk right next to me.

“I make sure that I’m fully allocating the time and the appropriate level of resources, and providing people with the space to thrive. So, I do space clearing—looking for barriers, hang-ups, bottlenecks…removing those so that people can bring their best to our work.”

CS: So, I want to go back to something you said. You said that we’re not there yet, but we’re in a different place. And I want to get a sense of what “there” is for you, or for the team—and where do you feel like you are now?

MW: Oh, I love it. “There,” for me, is very specific to the commitment that I made to myself to support GEO, when I started in 2019. That’s to stabilize the organization, to support the individuals within the organization to be fully competent and able to realize their professional goals and ambitions, and to position GEO as a catalyst for change in the philanthropic sector that brought together the best of what other PSOs [philanthropy-serving organizations] across the ecosystem also had to offer. Period. (I’ve never said that before, and it came out so clearly—I trusted that it would.) And so, that’s what “there” means for Marcus. The beauty of this is that “there,” for staff, evolves. Staff is consistently and routinely engaged in the cocreation of what’s possible through GEO—they’re given a set of parameters that are aligned with the mission. And so, it should change. As we attempt certain things and get clear about things over here, and deepen our practice together, other things should become clearer. It’s iterative in that way. And that practice is guiding our approach. The insight from participants as well as practitioners is what we prioritize to determine what’s next for the GEO community. So, it goes beyond Marcus. Marcus has provided a context within which this stuff can happen. And I make sure that I’m fully allocating the time and the appropriate level of resources, and providing people with the space to thrive. So, I do space clearing—looking for barriers, hang-ups, bottlenecks . . . removing those so that people can bring their best to our work. Establishing a routine, building trust among staff, and being able to then do the same with the board, and being able to then invite the ecosystem of partners and colleagues into something that feels like what I just described.

So, we had to be that first. You’ve got to be the change that you want to see. And we’ve done it on both the staff and board level, in the two and a half, three years that I’ve been here. Now, following the national conference, which was a critical milestone for us, it’s to continue to produce the kind of work in terms of products, as well as programming and experiences, that reflect that for external audiences as well.

CS: So, can you tell me about the conference? Because I sensed a big difference, and I can tell now from what you’re saying that that was maybe your first foray into bringing in the public. I’m wondering, How did you do that? Because I have my own experience as a participant, but I’m wondering what you were thinking or hoping that people would experience. I’m just wondering, Is the conference like a capstone-type thing in the organization? And it’s all to there and now from that? Because it is every two years, right?

MW: Every two years, yeah. So, I like the idea of a capstone, because that’s probably the term that resonates most with me. I think, in our spaces—philanthropic spaces—we may have too many conferences, if I can say that, or the conference spaces might be used with a different intention. So, what I mean by that is, as much as the posture of GEO was very explicit and intentional for the last national conference, it still felt like a traditional conference in many ways. And I think what we can look forward to is being clearer about the purpose of a conference: What’s the intent? What do we want to happen as a result of these resources coming to bear in that form? And how might we do that in a different way that perhaps has a geographic dispersion?

CS: You say you had a posture. Can you tell me a little bit about what the posture was that you were taking that was different?

MW: Yeah, the posture was: learning is important. So, coming together to learn still has value. We are building upon the historic reputation and function of GEO. And we have a point of view. So, it’s not just about consuming information and then doing whatever you want. Though, it never was! If you want to be most effective, here’s what we are learning is included within the most effective set of practices, strategies, ways of thinking and being, as it relates to leading change for the greater good, the greater societal good. That expression of “leading change” to direct philanthropic leverage for the greater societal good wasn’t always explicitly connected to the role of an effective grantmaker. We are doing that. And what I’m saying, and what the GEO community is reinforcing, is: “Grantmaker, you have power. And you are obligated. It is your obligation to cultivate that power in partnership with the other folks across the ecosystem (especially within your community locally) to imagine what’s possible, to design and conceptualize new strategies for change”— and that we are committed to change. No one is satisfied with the status quo.

CS: So, GEO is no longer just about effectiveness?

MW: No, no. We are always about effectiveness and we are underscoring that effectiveness is about change. In order to contribute to change, we also now have to practice and embody leadership. And, oh, my gosh, leadership is different from management, because management operates in the known sciences of organizational structure. But leadership is about moving through the unknown. It’s dealing with uncertainty, it’s grounded in change. It’s a discipline of responding to disruption.

CS: You’re basically creating a space for transformation.

MW: That’s it.

CS: This is really interesting, because I’ve been studying transformation for a while. You know, it’s very fascinating.

MW: It’s tricky.

CS: Very. Because it’s like you’re trying to go toward a place that you don’t know what it is yet, right?

MW: Every time. It’s so elusive, because of that very thing. And it can be scary. We’re dealing with fear. So, it serves GEO to be a space that welcomes every emotional state, including postures of resistance, and systematically work with people to acknowledge and release those postures. “Moving through” is how I have often referred to this process. We move through adversity. We don’t avoid it—we don’t even necessarily eliminate it, Cyndi. We acknowledge and move through. And then we notice whatever is present. What’s clear to us from here? What’s possible for living beyond those constructs that restricted us, restricted our capacity to dream and to thrive?

CS: I had a friend who does this work, and he calls himself a transformational consultant. And he would always be upset, because people would have all these issues in his space. And I told him, You call yourself a transformational consultant, so you have to understand the process of transformation. So, the way that I described it was comparing it to hiking. You are taking people on this treacherous trail to go up to the top so you can see something that you can’t see from where you are. You gotta be like, “Around this corner, don’t look down. ”

MW: That’s right.

CS: “There’s gonna be a hook; you’re gonna have to lift your left leg.” You have to almost preface and anticipate as much as possible. Imagine there’s a fog on that mountain, right? That’s what you’re doing, right?

MW: Let me add this to that amazing, amazing frame. While you’re doing that, what we know is that sensemaking occurs in community. We make sense of our experiences with other people. And so, going it alone, it’s only going to make the journey more treacherous. So, we have to take a pause and engage people in a process of: “So, you just turned that corner, we just went up that hill, how does that feel? What do you notice now? What is different now from before you started that? How was that burning-in-your-legs sensation? How did you respond to that?” So, the self-awareness is—oh, I love it. . . .

CS: I want to get back to this idea of the learning that’s necessary and the role of conferences in that. Because I agree. I’m not a fan of conferences. I go to very few. And the ones I go to are the ones that I feel like I’m actually going to get something from. They all have the same structure, for the most part. I love that you guys did the talks, those 20-minute talks, because I’m always looking for different structures. I think part of what makes it easier to curate spaces—at least for me—is that I’m such a critic. I’m like: Wow, this sucks. (Internally. I don’t tell that to people.) But I’m like, Why am I even here? I got on a plane, I’m in a hotel, I didn’t get anything out of this. When I had to design the Edge Leadership R+D space at NPQ, I thought: What kind of space would I want to be at that would actually be exciting? One of my guiding design principles is that complexity needs simplicity, in terms of structure. So, I was like, Okay, we’re going to have a really simple structure, and there are three things that we’re going to do across the day, but there are going to be three different ways to do it. And so, I studied the different ways that you shift culture. And there were three things: there’s a space for semiotics, which is thinking/words; a space for building, creating the forms we need; and a space for performativity, where people can start enacting and playing physically with what they’re trying to do. So, we rented a beautiful museum in Harlem, the Sugar Hill Museum of Art & Storytelling. They had a huge room. We hired a band to create a soundscape as people came in. We did everything so that people could shift, because we wanted them to shift while they were in that space—so, I had to create a feeling that when you came into the space, it was a different space. We welcomed participants when they came in and told them, “This is the semiotic space; this is the materiality space; and over there is the performativity space. You can be in any space; we’ll be doing the same thing across all three, just in different modalities.” And you could switch at any time.

MW: Yeah, yeah, that’s the key, though. Same thing, different modalities.

CS: They did not have to stay in one modality. I wrote a report about what we learned: People immediately knew that this was different. It has been said that if you want people to think different, you have to tell them that this is different. You have to act like it’s different. So, people came in, there was food, there was art everywhere, and spaciousness. It was interesting how it worked out. I remember my program officer from Ford went to the performativity space. Later, when we debriefed, many participants shared that they thought that the performativity space was the scariest. But they also noticed that participants were having the most fun in that space. There was a lot of laughing. The semiotic space started with looking at the barriers for leaders of color. They never moved from that.

MW: But you know, it’s both myopic as well as ineffective to focus exclusively on barriers. Many people and schools of thought affirm the value of including a focus on aspiration, possibility, what you want to experience or create, optimally. As human beings, this impacts our attitude, moods, emotions, as well as our beliefs about what is actually possible. It is generative!

CS: They intended that, but they didn’t start with that. Some people were mad. They had never had a space where they could process how they felt about all the barriers. The funders in the materiality space realized they didn’t know what to build. So, eventually, the people in the materiality space moved. They started to watch the other spaces. They said, “We don’t know what to build without anyone else. So, we can’t be building.” The performativity space moved through the agenda at twice the rate as the other two groups. Once people were encouraged to act different, and were told, “Here’s a way that you could do it, here are some games,” they just did it. So, one of them came forward with a challenge that he had at work. And we played a game called “Sit, Stand, Kneel,” where you have to shift your posture in response to what you say to the people who you’re talking to, according to shifts in power. And then he just started to come up with solutions, because he had to in order to move. So, it was really, really interesting. And so, I think about spaces a lot like that. And I’m wondering . . . NPQ used to host conferences, and now people are asking us to do that again. And conferences are a lot of work and a lot of money to put together.

MW: That’s the whole other thing. Sometimes it can feel like a waste of money!

CS: It’s a lot of money.

MW: I mean, relative to that money going into a singular experience . . . I want to invest that to yield a compound impact.

CS: Right, right. I mean, I’m not saying it’s bad, but it is a lot of money. Not just for the hosting organization but for everyone who participates, right? And for the earth, with everybody flying, right? I used to work at this organization a long time ago, a strategy center. And when we hosted conferences, the conferences’ visioning and strategy spaces for the field, it’d still be like 200 people, but everything was designed around workshops about things that people were going to do when they went back. And when they came, it started off with people presenting about what they had learned from before. So, it was very action based, and we included funders.

MW: So, do me a favor. Just as you do that, see GEO as a space that you are welcome to re-create. Let’s test something out together.

CS: Well, that’s what I was wondering. I’m thinking about how—because one of the things that I really want to move NPQ to doing is more directly talk to philanthropy.

MW: That’s what I’m trying to do, too. I’m exploring everything with you to try to figure out how we can direct this message, this conversation . . . and I couldn’t even say it right, there . . . have a conversation with philanthropy that moves us. That’s what I desperately seek. And Cyndi, we’re in our strategic planning process right now. I want you—I’m asking you, in this recorded conversation—to bring this idea that we’re talking about right now, around how we organize space, into our strategic pillar. I think we should be transforming spaces. Our mission is transforming philanthropic culture and practices!

CS: Invite me to your spaces. Let’s figure out how to do that.

MW: But that’s the thing: I had to learn. My first year, my first two years, was learning how GEO functioned in order to understand how it was not functioning, how it was malfunctioning. So it just took all of that time—it takes a long time. Reverse engineering, right? So, I’m just now there, to say, like, Ah, now I know the whos and the hows and the whats. How do I get you in a process early enough to inform the design? So, right now, I’m saying that the next opportunity is LA 2024—the next national conference.

CS: Let’s do that.

MW: It’s going to be a multimonth process. I know it is. 2024 might be a first iteration.

CS: What about if we did this another way? Remember, we talked about this before? The way that NPQ approaches the work is working at the different levels our readers are at. We design differently for three levels: fundamentals, practitioners, and edge. The fundamentals level is the people who are just trying to learn something.

MW: Supersmart, yeah.

CS: We don’t invest a lot in fundamentals. We create one-way conversations. We do webinars, we write articles, we have different ways of capturing the content. We organize, we curate, and readers take it in. The practitioners are people who already know a lot of this stuff. And what they want is the nuance and multiplicity, the connection to other people. How can they become better and better at whatever it is? How do they share what they know? And how do they get recognized and get resourced? So, that level is the second level for us, and we invest more in that level. But then we also invest in the edge.

Those are the people who are ready to create the next iteration of the work. So, the people at the edge are the people who we convene. Those are the closed circles that you’ve been part of. Those are the people who get fellowships. Those are the people who can come to us with a crazy idea and we’ll fund them to experiment on it and to publicize it so it becomes a known thing. That’s why I had the series of micro films that we funded. And it created a whole thing. Interestingly enough, the most popular one is the one about philanthropy.

MW: I’m not surprised.

CS: I don’t know if you saw it, but it’s kind of controversial: Swinging Philanthropy Dick Is Indecent.11 It’s based on the idea that abusing philanthropic power is indecent; that the culture that philanthropy creates with those norms is indecent.

MW: So, that’s a great example. One possibility for GEO is to be a space for folks to grapple with those insights, but to use art. That’s a new way of introducing dissonance, introducing a provocative way of thinking or an invitation to shift orientation. That’s what I actually want to do. And I think that’s what we can do right now. To your point, though, philanthropy is not at the edge. Philanthropy has been operating from the fundamentals level. It’s not even the practitioners’ level. GEO is perhaps at the practitioners’ level, but not consistently. And we don’t even go to the edge yet.

CS: Well, you know, it’s really interesting, because I wonder if there are elements that are at the edge that just haven’t had a chance to show up because the cultures can be so stifling. So, what if we did something? Because I often think . . .

MW: We can do that!

CS: In Design as Politics, Tony Fry writes about how what we design is political.12 He talks about why it’s so important to focus on the edge and to fund it to some extent, because even though it’s a small portion—usually it’s about 5 percent of people who are there—he argues that you don’t need any more than that.

MW: It’s always a small group.

CS: Always. And practitioners actually want that. When I talk about it, practitioners often say to me, “I know that I’m not at the edge, but I want to be next to the people who are at the edge, because I want to see where they’re going, where we’re heading.” I always imagine, What would it look like in a conference space to actually highlight the edge and to have everybody watch, so that they can go back and see from where they are? They don’t have to be at the edge, but how does knowing that that’s the edge influence what they do?

MW: No, I like that. Cyndi, there are colleague organizations that are more focused on edge. GEO—remember what I said earlier—we’re intentional about being the mainstream space. And so, we should be a constellation of all of them, with a primary percentage—the proportional majority—being kind of toward practitioners but acknowledging that it’s a whole lot of fundamentals level in there, and that people are going to be evolving through that.

CS: I feel like you did that at the conference. When I was there, I was thinking there should be levels. And the reason why—and some people don’t like this—but the reason why I think it’s important to have levels is because it’s important for people to situate themselves. At the conference, one thing that for me was really clear was which track was their fast track and which track was fundamental.

MW: You’re right. I’m going to affirm you in saying I didn’t have a heavy hand. I didn’t have the influence that I have now in that design. But what we did agree on is that we need something for folks who have already been practicing but are still developing proficiency. And we need to speak to . . . it’s the old “awake to woke to work.” We need folks at different developmental stages. So, we were trying to provide developmentally appropriate experiences and resources for practice.

CS: And you did it. There were certain rooms that I went into, and I was like, Oh, this isn’t my room.

MW: There was a reparations room—that’s still the edge for a lot of funders—but it was a very good one. There was a lot of traction around how the Evanston Community Foundation is doing their reparations work. It’s not as scary as it once was. And I think it’s becoming more of a mainstream conversation.

CS: I did an article last year on Black funds.13 Many readers responded to that article. One told us there are over 100 of them now.

MW: Whoa, yeah, they’ve started to increase a lot in the last three years.

CS: It’s pretty radical to have Black funds. I mean, I’ve been seeing a few of them. I didn’t realize it was way more widespread.

MW: I’m telling you . . . I’ve been searching with you around this. You’ve been so patient, thank you. The reason I want to take the time and get this—and I don’t mean perfect . . . but make sure that we’re bringing something that we can offer consistently—is because GEO is operating from its strength, and in order to do that, I had to set the table over these past couple of years. And we have that in place now. So, we can provide the infrastructure for you and whomever the other colleagues are, to be the creative guides. You’ve got the vision; our folks are interested in the execution, and they want to become practitioners. They want to get really good at this thing that we’re talking about.

CS: I love the idea, because I’ve heard a lot of people, including funders, talking about this, about the need to really move the funding space, and I get why it’s in the fundamentals space. It’s to be expected. And I love what you said about the intimacy not being in their personal lives and then being asked to do that, because that is so real.

MW: Yeah. And Cyndi, you asked how I did whatever I’ve been able to do so far at GEO—and it’s by being a learner. By shifting my orientation—constantly. The practice is the discipline of orienting myself into the learning posture. It just is—because everything is a synthesis. It’s informed by the people who are right there. The real thing that we’re trying to do, I believe, is tap into the collective genius of the people who are in a particular situation, who are involved. They’re there because they have all of the pieces that are required to build that puzzle. That particular puzzle in that moment can be built by everyone involved in that. I believe that. That’s the spiritual practice. It has taught me that. And you being present with me over the years of our relationship, and the changes that I’ve been able to witness? Oh, my gosh. I remember being in your office. It wasn’t even painted the same color. I remember being with you in Boston. We’ve invested time with each other. That’s what we want to offer to our colleagues in the field, right? It’s not just a job. It’s a lifestyle.

CS: Well, we can invite them into it, because I think that that’s a really high-level invitation. Do you know Peter Block’s book.

MW: Community.14

CS: Community, right. He talks about the invitation. How sometimes when you tell people, “This may not be for you, these are the hurdles,” that actually makes it more enticing for the people who are ready.

MW: So, what if we think about piloting? That’s the last thing that occurs to me to share. In order for us to move on the moment, what might we pilot on a smaller scale in the near term?

CS: You know, honestly, I think of it as experimenting. It’s funny, because I think you and I have a lot of similarities, but we also have different approaches. And I think that’s what makes it good, because you’re like, “I’ve gotta go slow,” and I’m just always moving really fast. But it’s good. It’s good. I like that. I feel like groups need to have this kind of difference of approach.

MW: I agree. And I always surround myself with people like you. I do. I do it intentionally, because I can be like that, but I’m more impetuous. And so, when I slow down. . . .

CS: It takes a lot of patience, Marcus, so I salute you on that.

MW: But I salute you, because I can’t move that fast or else I start skipping steps and I don’t bring my best. When I slow down, that’s when the magic happens. Yeah.

CS: So, one thing that I think we could do: I have been playing around with this idea of a VoiceLab for funders to deal with race—racial justice in philanthropy. Funders have been asking us for this. And I wonder . . . I’ve been hesitant, because it takes a lot to host a VoiceLab. But I would host one like this. And it could actually be less intensive than the first one I did, which was for leaders of color who were articulating new ideas and creating new forms.15 It could meet just once a month. We could really make it manageable. But what if we had a VoiceLab that people—funders—opted into that leads up to the next conference?

MW: Ohh!

CS: Right? So that next conference, somehow . . . maybe it’s a track or something—maybe it’s like the keynote . . . I don’t know. But let’s give people first an opportunity to grapple. They don’t have to be at the edge, but if they want to try to be at the edge, and we could talk about things . . . I mean, it could be a space where we talk about power but we also talk about what their experiences are. And we just ideate a lot and really try out things and see—with the idea that what we’re doing is preparing for this conference next year.

MW: That, Cyndi, is beautiful. I would even say, not only are we preparing for the conference but we’re preparing ourselves for the leadership journey that the era is revealing. This is revelatory. You know that whole emergent strategy . . . this is what it means to be in emergence. Alignment. To lead in a completely different way.

CS: Totally. Just like the pro-Black work we started last year. I mean, we have a book coming out this summer that came from a conversation last year around this same time, where we hosted a conversation on what needs to happen for us to really advance the DEI/Racial Justice work. And people immediately said, “We need to start talking about pro-Black.” But they also thought, “We can’t do that.” And I was like, “Well, we are gonna do it.” And they were like, “We are?” We didn’t even know if we knew anything about it. What do we know about that? We had to get a different binding for that issue because it was so big. Collectively, we actually did know a lot about it.

MW: See, that’s so bold. I love it. I’ve seen you do this.

CS: Oh, my god, Marcus. And you know I brought those magazines to your conference, right? Like, they went like that. [Snaps fingers.]

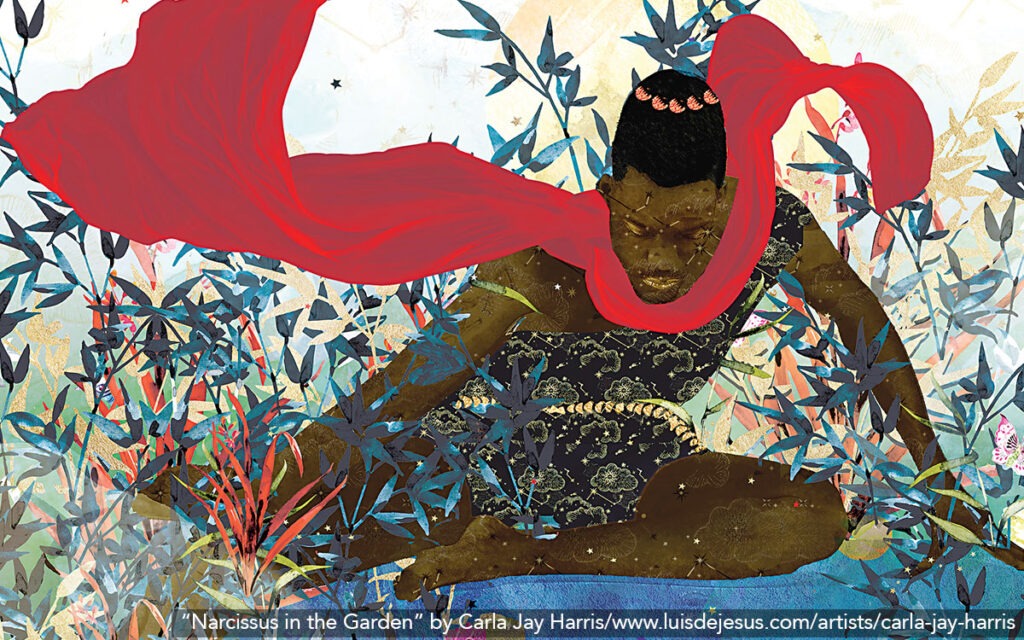

MW: Is that the one with the woman, like, the mosaic? I keep that!

CS: Everybody loves that. That was our most popular issue in the history of the magazine.

MW: My goodness, this thing is right around here somewhere. I look at this thing every day.

CS: Everybody tells me this. I would go to conferences and people would tell me that they kept the magazine next to their beds, or read it in the morning, for inspiration, especially given the context we’re experiencing. And people wanted the hard copy, Marcus. It wasn’t enough just to read the articles online.

MW: That’s right. And this voice lab idea? If I’m understanding this correctly, the voice lab would involve the Maurice Mitchells—like, we would have all these guests come. I think of it as Friends of Cyndi.

CS: It could be, yeah. But we would definitely have a space where people would be hearing what the field wants.

MW: That’s what we want, that’s what we want.

CS: And then people would be having space to think about that and to talk honestly about what that feels like for them, and to experiment.

MW: I’m saying yes, because we got approval and support to do work that contributes to racial healing. I’m defining racial healing as addressing the disproportionate impact of inequities on individuals toward being able to live beyond constructs, toward being able to shift our orientation toward a more liberated stance, a more creative stance for thriving. And so, this voice lab, to me, it’s really like a platform to facilitate racial healing. So, it’s like that. It’s racial equity, healing, and reconciliation. That’s the framework that is starting to evolve in my most recent iteration of this work. Because equity is one step. It’s an analysis, it’s a set of practices, it contributes to and involves healing. And then once we heal, we can engage in some active reconciliation, because it takes all hands on deck to realize the potential of this nation. It won’t be just a group of Black people that’s gonna bring this nation to its fullness. It’s gonna be all folks grappling with the impacts of inequity on how they think about what’s possible, and releasing ourselves from these scarcity mindsets and other limitations.

I’m committed to this infrastructure serving this shared vision that we have around living beyond the constructs—because that’s where people want to be.

CS: I think that’s gonna be the title of this interview.

MW: Let’s go!

CS: All right. Thank you. As you share two hours. . . .

MW: I prepare for that when I talk to you, because it’s real. Listen, this is the energy practice that we talked about. We are raising consciousness, our own consciousness, expanding and allowing for that revelatory force to come forward. I know that’s what happens when we get together. So, respect.

CS: Take care, Marcus. Big hug to you. I’ll talk to you soon.

MW: You, too. Thank you

Notes

- Maurice Mitchell, “Building Resilient Organizations: Toward Joy and Durable Power in a Time of Crisis,” NPQ, The Forge, and Convergence, November 29, 2022, nonprofitquarterly.org/building-resilient-organizations-toward-joy-and-durable-power-in-a-time-of-crisis/.

- Cyndi Suarez, The Power Manual: How to Master Complex Power Dynamics (Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers, 2018).

- Marcus Walton, ”Leading While Black: A Story of Double Consciousness, Decolonization, and Healing,” NPQ, November 2, 2020, nonprofitquarterly.org/leading-while-black-a-story-of-double-consciousness-decolonization-healing/.

- In this issue: Cyndi Suarez, “Leadership Is Voice,” Nonprofit Quarterly Magazine 30, 1 (Spring 2023): 90–95.

- The Yogic Encyclopedia, v. “siddha,”accessed March 7, 2023, ananda.org/yogapedia/siddha/.

- Michel Foucault, Fearless Speech, Joseph Pearson (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2001).

- Jayaram V, “The 36 Tattvas and Their Significance,” Saivism.net, accessed March 7, 2023, saivism.net/articles/tattvas.asp.

- See for example john powell, “Bridging or Breaking? The Stories We Tell Will Create the Future We Inhabit,” NPQ, February 15, 2021, nonprofitquarterly.org/bridging-or-breaking-the-stories-we-tell-will-create-the-future-we-inhabit/.

- Giovanni Derba, “Matrika Shakti,” Matrika, September 11, 2015, matrika.co/en/matrika-shakti/.

- “Sheryl Petty,” Omega, accessed March 8, 2023, eomega.org/workshops/teachers/sheryl-petty.

- Saphia Suarez, Swinging Philanthropy Dick Is Indecent, Edge Studios, September 14, 2022, written and directed by Saphia Suarez, video, 4:01, youtube.com/watch?v=b3fZkXUw320. And see Saphia Suarez, “Swinging Philanthropy Dick Is Indecent,” NPQ, September 15, 2022, nonprofitquarterly.org/swinging-philanthropy-dick-is-indecent/.

- Tony Fry, Design as Politics (New York: Bloomsbury, 2010).

- Cyndi Suarez, “The Emergence of Black Funds,” NPQ, June 21, 2022, nonprofitquarterly.org/ the-emergence-of-black-funds/.

- Peter Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2008).

- See “One of the most powerful things you can do as a leader is articulate things that are not yet clear,” The VoiceLab, accessed March 7, 2023, edgeleadership.org/.