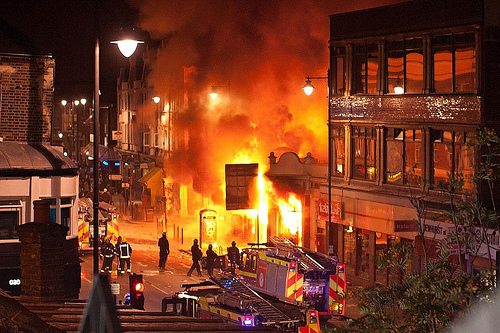

It is hard to watch the news of civil unrest enveloping poorer and minority neighborhoods in London, Birmingham, Bristol, and elsewhere in the U.K. (Gretchen Carlson on “Fox & Friends” today called the riots “racially charged,” a piece of terminology that we find somewhat offensive.) What do the riots in U.K. cities tell us about conditions there—and is it a preview of what might occur in this country, given all the talk from U.S. lawmakers of future austerity measures and special deficit reduction “super committees?”

A Reuters analysis suggested that the unrest in the U.K. might be linked to a combination of massive spending cuts and “a widening gap between rich and poor.” One high-level executive consultant, Pepe Egger, said that the riots were “the result of decades of growing divisions and marginalization, but austerity will almost certainly make it worse. Yes, the police can restore control with massive force but that is not sustainable either in the long term. You have to accept that this may happen again.” Offering a perspective from the street, a young person from London’s Hackney neighborhood criticized bankers and politicians who got wealthier and more self-indulgent while the poor suffered program cuts: “Everyone’s heard about the police taking bribes, the members of Parliament stealing thousands with their expenses. They set the example,” he said. “It’s time to loot.”

But what of the charities that Prime Minister David Cameron was trying to empower via the Conservative Party’s “Big Society” concept? Commentary in the British press suggests that the role of charities is more than a bit constrained in an environment of huge cuts in social programs. But the Big Society is also hampered by limits on what charities can realistically accomplish.

Writing in The Guardian, Simon Jenkins decried the inadequacy of “Whitehall-ordained public services, now retreating ever further into centralised bureaucracy . . . [and] ‘big society’ charities, losing money and lacking accountability. There is no substitute for proper, open, responsive democracy at any tier of government.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The BBC’s Matt Prodger linked the Tottenham riots in part to recent 75-percent cuts in the borough’s youth services budget. He noted that “it is the so-called ‘soft’ services like youth clubs and initiatives that help keep young people out of trouble and which nationally the Education Select Committee says have been cut more than any other.”

Cameron’s Big Society was supposed to devolve more responsibility to local charities, allowing them to design their own responses to social problems. But a correspondent for France 24 declared that the Big Society plan was “in tatters,” having literally gone “up in smoke.” A spokesman for a Labour Party-allied community group, Movement for Change, said that the riots proved that “Cameron’s big society is a failure…[little more than] a PR move designed to paper over the cracks in government spending.” Back when the austerity measures were enacted, some people predicted that the cuts in government spending would lead to riots in the summer of 2011. At the time, it sounded like typical political hyperbole. But then it actually happened.

An editorial writer for Australia’s The National asked a very pointed question prompted by the Cameron government’s stunned reaction to the riots: “What price David Cameron’s Big Society as Tottenham, the most solid of communities, lies in ruins? The notion that small-state Britain can be run along the lines of Ambridge parish council by good-hearted, if underfunded, volunteers has never seemed more doubtful.”

The causes of and solutions to civil disturbances are complex and confusing. Just ask anyone who has lived through one, such as the riots that broke out in several cities following the shooting of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, or in Miami’s Liberty City and Overtown neighborhoods after the killing of African-American motorcyclist Arthur McDuffie in 1980, or in South Central Los Angeles in 1992 after the acquittal of the police officers who beat Rodney King, or in Cincinnati in 2001 following the acquittal of a police officer who shot an unarmed African-American youth. While racism and inequality undoubtedly played a role in all of these terrible events, each one was characterized by a unique set of circumstances that make it difficult to generalize.

Trying to boil down the causes of complex social phenomena to single data points, such as cuts in youth programs or increases in an already wide wealth gap, is pretty fruitless. But it’s important to recognize how the weakening of critical social safety net programs and the widening wealth gap contribute to and exacerbate the conditions that fuel unrest.

Even more crucial may be the recognition that the Big Society’s weak response to the U.K. riots suggests that if human service providers continue to absorb the body blows of serial program cuts from federal, state, and municipal authorities, we risk a repeat of the experience in London. With crippled government and charitable funding streams and an increasing reliance on volunteers to take the place of well-paid and well-trained staff, nonprofits here in the U.S. might find themselves, like their British counterparts, watching a police response when ultimately a different kind of short-term and long-run solution is needed.—Rick Cohen