June 23, 2019; Truthout

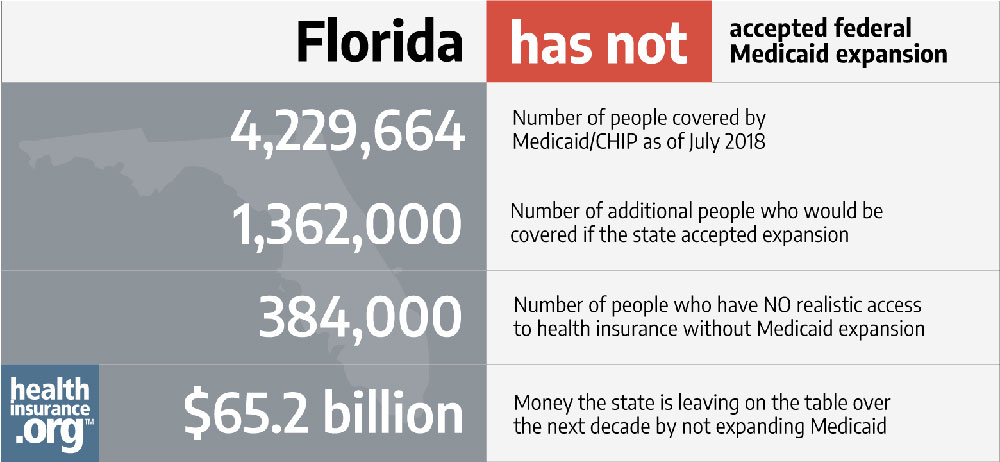

After the 2018 election, three states (Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah) joined the 33 that had already extended Medicaid coverage, as the Affordable Care Act originally envisioned, to all residents earning 138 percent of poverty-line income. But there are still 14 states where about 2.5 million residents earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but too little to qualify for subsidies to purchase private insurance. Now, however, reports Rebekah Barber in Truthout, efforts to extend health insurance coverage are gaining ground in three states: Florida, Mississippi, and North Carolina.

On average, in the 14 non-Medicaid-expansion states, health coverage for parents ends if they earn more than 43 percent of poverty-line income—a paltry amount that in 2018 worked out to $8,935 for a family of three—while federal subsidies for the purchase of private insurance only become available if you earn at least 100 percent of poverty-line income. Nine of these 14 states are in the South, and these states include approximately 92 percent of the 2.5 million people who are in this “coverage gap” zone, according to a March 2019 Kaiser Family Foundation report.

The health insurance gap in these states has real life-and-death consequences. A 2018 study from the Center for American Progress estimated that expanding Medicaid coverage would save 2,323 lives a year in Florida, 481 lives a year in Mississippi, and 1,155 lives a year in North Carolina. Barber notes that studies have shown more broadly that Medicaid expansion results in “more timely treatment of Black cancer patients, decreased infant mortality rates, fewer deaths from cardiovascular conditions, [and] more accessible treatment for opioid addictions.”

The campaigns to change these numbers in Florida, Mississippi, and North Carolina share the same goal, but the path pursued in each state differs. In Florida, where 445,000 people are in the coverage gap, a petition campaign has been launched. So far, the campaign has collected over 81,000 signatures, enough to trigger a Florida Supreme Court review of the petition’s wording. Provided the state supreme court signs off on the petition’s wording, the petition organizers will have until the end of 2019 to collect at least 766,200 signatures to qualify for the November 2020 ballot. Approval would require a 60-percent yes vote—a high bar, but one that was successfully met by a campaign that restored voting rights to 1.4 million former prisoners last year.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In Mississippi, where 300,000 people are in the coverage gap, the Mississippi Hospital Association (MHA) has proposed a plan called Mississippi Cares, which expands Medicaid but seeks to label it “reform” as a way to build Republican support for the measure. Barber notes that it is modeled after the “Healthy Indiana” plan, with a partnership approach that involves the state, private hospitals, and Mississippi True, which is an MHA-created insurance company. The plan would require participants to pay a $20 monthly fee and a $100 copay for certain non-emergency hospital visits. According to MHA head Tim Moore, the fact that “uncompensated care costs in Mississippi are exceeding $600 million annually” drives the MHA’s proposal.

In North Carolina, 500,000 people would benefit from Medicaid expansion. Last November, Democrat Roy Cooper was elected as the state’s governor, but both houses of the legislature have Republican majorities (29 of 50 seats in the senate and 65 of 120 in the house). Here, activists have engaged in public demonstrations in an effort to strengthen Cooper’s hand in budget negotiations with the state legislature. Barber notes that earlier this month, “North Carolina activists held 22 simultaneous vigils across the state earlier this month to remember the thousands of people who have suffered and died in the state for lack of health care and to call on Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper to veto any state budget proposal passed by the Republican legislature that does not include Medicaid expansion.”

“People are dying across North Carolina each and every day we fail to expand Medicaid,” said attorney Jackie Kiger at a vigil in Asheville. “More than a thousand people die each year.”

Buttressing the campaign too was a state summit on the opioid crisis held this month, which cited expanding Medicaid as “the most important step to reduce opioid addiction and deaths.”

In all three states, prospects for expansion remain uncertain, although clearly Democrats are pushing hard in North Carolina, as is the hospital association in Mississippi. Slowly, though, the number of states expanding Medicaid seems likely to increase. Initially, when the Affordable Care Act took effect only 24 states agreed to expanded Medicaid coverage; gradually that number has grown to 36. Soon, perhaps, a few more could be added to that number.—Steve Dubb