The mantra of philanthropy now more than ever is: create public-private partnerships between foundations and government agencies. Nationally, big foundations have ensconced themselves in the Obama administration, promoting concepts of entrepreneurialism and innovation in such high visibility, high glitz programs as Promise Neighborhoods. Modeled on the “whatever it takes” Harlem Children’s Zone initiative and the Social Innovation Fund, such programs aim to capture and replicate “proven successes.”

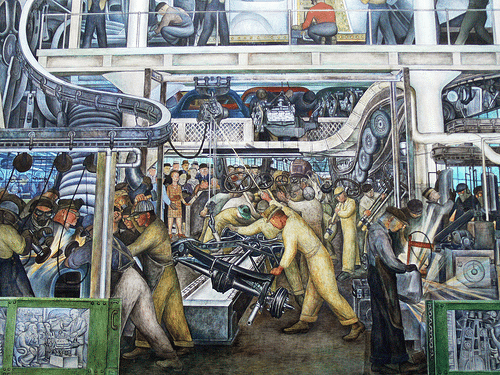

But what if there is no glitz? What if there is no proven success to replicate? The challenge of turning around a dysfunctional, broken city – not a small town or urban neighborhood but an entire city, whose back is against the ropes and which is in many people’s eyes all but dead – is a mammoth undertaking. That’s Detroit: a city spiraling downward as its automobile-manufacturing economic base all but disappears — along with much of the population. It’s a city that a variety of Detroit-area and national foundations have committed to help, but the challenges are clearly complex, the problems are more than intractable, and the despair of residents is palpable.

Recently, a Wall Street Journal article suggested that some of the foundations – the Kresge Foundation in particular – helping Detroit get back on its feet, were engaged in a contentious relationship with the city as the revitalization process lagged on. Can foundations and local government work together in a public-private partnership aimed at reversing the downward trajectory of one of the nation’s most troubled cities without ending up at loggerheads? Can private foundations, accustomed to operating often with a large measure of immunity from the public (and the press), participate in a process requiring accommodation of the pressures and dynamics of local politics? Can local government take advantage of the presence of large foundations willing to put dollars on the table without feeling that foundation dollars come with too many strings and too much pressure for foundation control of the process? Are the tensions between philanthropy and government in Detroit natural and to be expected, or are the leaders and key players due to obstinacy and myopia undermining the prospects for progress and success against Detroit’s seemingly intractable decline?

It is hard to imagine anyone's not having a sense of the perfect storm that has been battering Detroit for decades. Two indicators suffice as evidence of the city’s malaise. First, Detroit was (and still is) a major metropolis, but after reaching a high of 1,849,568 in 1950, the official city population began to shrink — declining 9.7 percent to 1,670,144, in 1960, another 9.3 percent to 1,514,063, in 1970, and a daunting 20.5 percent to 1,203,868, in 1980. Then came a 14.6 percent drop to 1,027,074, in 1990, another 9.5 percent decline to 951,270, in 2000, and, finally, a shocking population plummet of 25 percent to 713,777 — as reported in the 2010 census. In the postwar era, Detroit has lost an entire large city’s worth of its population — more than the entirety of Boston, or San Francisco.

Clearly related is the city and metropolitan area’s picture of unemployment. Around May of this year, the official unemployment rate of metro Detroit was 11.6 percent, significantly higher than the national unemployment rate of 9 percent at that time. But for the city of Detroit itself, unemployment was 20 percent – down from the 28.9 percent unemployment rate that the city reached in fall 2009, but still extraordinary. One suspects that the number of unemployed was only as low as one-fifth of the labor force, due to people’s leaving the area to look for work elsewhere, as well as dropping out of the labor force altogether, discouraged by their virtually nonexistent employment prospects. A logical rule of thumb is to calculate “real unemployment” as a combination of those looking for work, those who have given up, and those who are underemployed – that is, working part-time because they cannot find full-time work — which usually calculates to double or more the official unemployment rate. The situation in Detroit isn’t helped by the fact that 47 percent of Detroiters are considered functionally illiterate. These are Great Depression–like numbers focused on one struggling city.

What does a city do when confronted with such conditions? And what does a philanthropic community do? In Detroit, the foundation community has a strong history of commitment to community betterment even as macro-economic factors undermine the city’s economic prospects. Foundations such as the Skillman Foundation, the McGregor Fund, the Hudson-Webber Foundation, and others have been in the trenches, working with City Hall and such major anchor institutions as Wayne State University to fashion programs and strategies to counter the city’s downward spiral. In recent years, national foundations have taken active roles in the struggle, notably the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and the Ford Foundation. Detroit’s foundation community is a resource other troubled cities lack. As Linda Smith, executive director of the community-based U-SNAP-BAC development organization, noted, “We’re a city that’s broke, [so] any help that’s not dirty money” is important to seek, use, and leverage.

The Kresge Foundation took a high profile role in Detroit’s revitalization strategies some half dozen years ago, when it recruited Rip Rapson, one-time president of the McKnight Foundation in Minneapolis, as its new CEO. Rapson’s history at McKnight (and, previously, with roles in the Minneapolis city government as well as in academia) led to Kresge making some large financial investments in support of Detroit’s redevelopment, in partnership with the region’s other foundations. Along with Kresge, the Detroit foundations now meet regularly, share information, pool resources (on occasion), work with city agencies, and collaborate more actively than ever before.

The notion that philanthropy, or philanthropy-plus-city-government, could possibly turn around a half-century of decline on its own is preposterous. It would be impossible for a new Detroit – one with a new economic base and the resources for positive growth and change – to be predicated on foundation grant making and municipal tax revenues, but the foundations and the city were committed to laying the groundwork for a new vision for the battered and beaten city. The new mayor, Dave Bing, was an important element in this push (his predecessor – the “hip hop” mayor, Kwame Kilpatrick — had been hauled off to the slammer for malfeasance and corruption). The electorate, the foundations, the business sector, and the nation welcomed the election of Bing, a man without previous political experience who embodied an upright and honest City Hall.

SUBSCRIBE | Click Here to subscribe to THE NONPROFIT QUARTERLY for just $49

So, given how difficult the situation has been and how hard the foundations and the mayor have been working, everyone was stunned to read a front-page article in the Wall Street Journal suggesting a near standoff between the foundations and the city government over revitalization strategies. The article seemed to suggest that the Kresge Foundation and the Mayor’s Office were at loggerheads, and inferred that Kresge was withholding financial commitments because of unhappiness with the city’s leadership. According to the article, the city felt that Kresge was trying to call too many shots and to dislodge the city and mayor from their leadership functions. Also, apparently, the foundation was impatient with the city’s attenuated and sometimes politicized decision-making processes, the city was increasingly distrustful and dissatisfied with foundation-recruited-and-paid-for “outsiders” brought in as experts for parts of the revitalization strategy, and neither side was happy with the other’s concepts of and plans for community participation.

The story was embellished with photographs of a stern – and white – Rip Rapson, standing in the middle of Woodward Avenue – the site for a planned light-rail corridor – juxtaposed with pictures of African-American Detroiters said to be concerned about how they would be affected by the progress or lack thereof of the vision of a new Detroit. The article seemed to stun and trouble Rapson. In his view, the WSJ writer“ chose to go back to the old narrative, racial divisions, white philanthropy, and there’s some truth to all of this.” Rapson firmly believes that the partnership between foundations and the City now “is more than optics, it’s real people doing real work in real time,” a theme he felt the article overlooked.

Given that Kresge had already made the philanthropic investment of more than $100 million in such Detroit improvements as a riverfront promenade and incentives for entrepreneurs – money that other cities could only dream of – outsiders looked at the article and wondered how the partnership between the foundations and the city could be falling apart when there was such a clear need for consistent, ongoing investment.

Through conversations with a select number of people – both inside and outside of Detroit – whom we have grown to rely on over the years for clear-eyed thinking about the city, we explored whether the stalemate portrayed in the Wall Street Journalwas simply a communication problem – perhaps an instance of a foundation executive and city officials speaking with unusual candor and openness to the press – or a more serious power struggle between the elected government of more than 700,000 people and an influential, unelected array of private foundations.

In a way, both played a part in the conflict – leavened with and exacerbated by other factors. And, in truth, it is somewhat logical and natural for this type of friction to occur between foundations and local governments when faced with a challenge like Detroit’s. That any sector – business, philanthropy, government – on its own, much less sectors marching together, could design and carry out a strategy to undo Detroit’s conditions without moments of dissension and strife is simply unrealistic. Detroit is no fairy tale, and the challenges it confronts are a harbinger of what other cities may face with the disappearance of their economic base: a national economy that demands synoptic changes, and cash-strapped federal and state governments with little to offer.

The following are the striking details of the Detroit/Kresge story offered by our informants:

Why only Kresge? The WSJ article made it seem as if Detroit had turned into a one-foundation city. Not only were no other foundations mentioned, even initiatives frequently associated with other foundations – such as the effort to attract new young residents to Detroit’s Midtown area, long a priority of the Hudson-Webber Foundation for example – were attributed to Kresge. Other major foundation programs, such as the pooled $100 million “New Economy” initiative run through the community foundation, involve the range of foundations that are not only providing capital but also participating actively in the governance and decision making (as opposed to simply handing the money over to the community foundation and hoping that some useful economic development activity occurs).

While it might be Rapson’s still relative newness to the Detroit area – only five years at the helm of Kresge – that made him perhaps more open and unguarded with the press than others might have been, we suspect it is the structure and dynamic of the foundation collaboration that led to the laser focus on just that one foundation among the many involved in Detroit redevelopment programming and funding. While the foundations work together and communicate, each foundation tends to take the lead in one area of activity. Kresge is the lead on two of the most contentious elements of Detroit planning: the push to consolidate Detroit’s scattered population into a number of neighborhoods while mothballing much of the rest of the vacant land and buildings for future alternative uses, and the construction of a light-rail line from Detroit’s Downtown going north, providing a means for Detroiters to get to suburban jobs, and giving suburban residents access to the city’s cultural and Downtown attractions.

The history of urban renewal in Detroit still embitters much of the city’s population, for whom memories of entire neighborhoods being displaced to make room for highways, automobile plants, office developments, and more, linger. The goal of the Detroit Works project is to create livable neighborhoods with a critical mass of residents, as opposed to the structure of many of the neighborhoods right now, which are a mix of scattered occupied buildings, multiple vacant buildings, and rubble-strewn lots left over from demolition. But that means making people move. Who moves, to which neighborhoods, when, and with what support becomes the high-wire part of the planning associated with Kresge, and as such makes Kresge a flash point for stresses and strains.

There are other contentious areas in the remaking of Detroit, such as the bankrupt public school system, which is in virtual free fall and has the Skillman Foundation largely in the lead foundation role. But as raw as most school issues are for most residents, they pale compared to the prospect of being told to move to who knows where. The CEO of the Living Cities foundation consortium, Ben Hecht, described the land use issue as the “one [strategic component] that has the most friction . . . the land has to be repurposed, and Mayor Bing has put a lot of political capital on the line.” U-SNAP-BAC’s Smith said that the neighborhood consolidation issue is the one that people bring to her: “People are constantly asking me about whether my neighborhood is going to be shut down, and the mayor doesn’t have an answer [yet].” Community people focus on “what they can do to make sure that their neighborhood is included in the revitalization,” not the long term planning and revitalization issues. It shouldn’t be surprising that such a contentious issue makes Kresge as the lead foundation, and the Mayor as the political leader, vulnerable and sensitive.

Scale of change: This is not a project made up of small foundation-supported, neighborhood-based strategies. The Detroit Works plan is the remaking of an entire city, not just a process of fixing up neighborhoods and bringing back jobs and industry. The Detroit of the future will not be the Detroit of the past. The old mono-industry economy of Detroit is dead. The city’s future will be based on an economic shift to something new and different, because the automobile-based manufacturing of the region, even with the Obama administration’s successful bailing out of General Motors and other manufacturers, is not going to be the economic engine of the future. Detroit is in search of a different reason for being. Its neighborhoods are going to be radically different – some neighborhoods, if the project develops as planned, may no longer exist.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This is an unprecedented scale of planning and change in a large city – a high-risk maneuver without truly parallel models to draw on. There are few if any guideposts or benchmarks to give the players — residents, city officials, and foundations — the kind of security they might want for the future. It is all but guaranteed that there will be moments — perhaps even prolonged periods — of tension and disagreement as well as confusion, disarray, and hopelessness during the regeneration process. It should be expected that a foundation executive might express exasperation at his City Hall partners, and that a mayor might bristle at the notion of foundations seemingly taking undue amounts of leadership and control, when the stakes and scale are as large as Detroit’s, and the uncertainties so obvious and unanswerable.

Different time zones: The Wall Street Journalnoted Rapson’s use of the term “syncopation” to describe Detroit’s landscape – in jazz terms, a pattern of stronger and weaker beats. But observers have suggested that perhaps the metaphor would have been better applied to the timing of the foundations and the city. As slow as many people think foundations are in their decision making about grants, foundations have much more flexibility with their decisions than do city officials. The political time frame is different from the private sector’s, as politicians have to work through multiple decision-making nodes, various bureaucracies in municipal agencies, and legislative bodies such as city councils to get decisions negotiated and approved. This can often frustrate foundation people who, once they have agreed to an investment strategy like that of Kresge and the other foundations, can move with alacrity.

Some of the time challenge is due to pressures the city feels that might not necessarily be felt as acutely in the private foundation community. For example, Detroit has long maintained that it didn’t get its fair share of federal program resources; so, according to the Local Initiatives Support Corporation’s Detroit program director Tahirih Ziegler, with a different leader in the White House, “there are a number of federal resources coming into Detroit with time deadlines and constraints, pressures to make sure that moneys are allocated.” As Ziegler explained, the city government has to deal with “different pressures than what the philanthropic community is feeling or having this moment in time,” and foundations have to better understand that federal grant dollar pressure.

What makes the time frame issue more pronounced is the fact that political leaders change with elections (or, in the case of Mayor Bing’s corrupted predecessor, with indictments and convictions). The Detroit Works plan is a long-term strategy, and the foundations undoubtedly look at the city’s convolutions and worry that by the time they have cut a deal and made an investment with the city, there could be a new mayor in City Hall. Or, agreements might be undone by a recalcitrant City Council — and Detroit’s City Council has been notoriously difficult in its relations with Mayor Bing (and his predecessors). The City Council frequently feels left out of the loop, and, as a result, sometimes functions as an obstacle, operationalizing the objections of portions of the city’s population to such City Hall decisions as shrinking and consolidating neighborhoods. As one observer said, “if I don’t like what’s going on, I go to Council and that stops everything.” The foundations want things to move quicker – without politics — but the city wants the foundations to understand the real-time political constraints that make some of those things difficult.

FREE DELIVERY | Click Here to sign up for THE NONPROFIT NEWSWIRE, Delivered Daily >>

Carol Goss, president and CEO of the Detroit-based Skillman Foundation summed up the challenge faced by both the foundations and the city as requiring recognition of different operating cultures. “We have to understand how government works and how philanthropy works, they’re different,” she said. “It’s not as easy to move an agenda in the public sector as in philanthropy.” For many foundations, appreciating the real world of local (and national) politics is an essential factor in making public-private partnerships work. Even the most well-intentioned philanthropist, accustomed to the flexibility and autonomy of foundation grantmaking, sometimes has to be reminded that democratic government faces understandable operating constraints that limit flexibility and require the participation of multiple decision-making bodies.

Questionable capacity: There was some truth to the Wall Street Journal’s report of city government dissatisfaction with foundation-recruited outside experts. Much of the commentary focused on Toni Griffin, a talented planner the foundations recruited from Newark, New Jersey, to lead the planning effort for Detroit’s neighborhoods. Less overtly addressed in the article was municipal discomfort with the experts recruited to design a new approach to community participation in strategic elements of the Detroit Works project. The implication was that these outsiders didn’t (or couldn’t) “get” Detroit, and that it was all well and good that they possessed certain expertise, but more necessary were the local experts who knew the political and social topography of Detroit inside and out.

After some initial rocky moments, observers noted the need for relationship building between the outside experts and city leaders. But the WSJ article implied more problems with the “outsiders” than our sources suggested. The impression from our interviews were:

· In Detroit, like in many other cities, the resistance to outsiders is a default position against change. The message is, “Oh, that worked in that city, but that can’t work in Detroit, we’re different.” You can substitute any other city for Detroit and that message is heard frequently. It doesn’t work. For cities in the kind of distress that Detroit faces, the challenge is to find, adapt, and deploy ideas that have been successfully applied elsewhere. In fact, one of the most widely applauded elements of the Detroit plan has been the Detroit Revitalization Fellows Program, funded by Kresge and Hudson-Webber, whose mission is to recruit young, mid-career professionals (roughly half from Detroit and half from outside) and put their talents to work with local Detroit organizations, such as the University Cultural Center Association, , the Downtown Detroit Partnership, the City of Detroit, the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation, and the Woodward Corridor Initiative. These two-year, full-time employment fellowships, to be managed by Wayne State University, are based on a model adapted from the Rockefeller Foundation Redevelopment Fellowships developed in 2007 in New Orleans, after Hurricane Katrina. (The New Orleans program was administered by the Center for Urban Redevelopment Excellence at the University of Pennsylvania.)

· Everyone we talked to suggested that Detroit lacks the capacity – staff capacity, specifically – to take on some of the massive problems. This wasn’t a knock at the people working in the Detroit bureaucracy but simply a recognition that Detroit is understaffed, that there has been lots of turnover at the top levels of city government (including some of Mayor Bing’s top lieutenants and city agency heads), and that new people with new ideas are needed. How else to explain Detroit’s schools’ being turned over to former Washington, D.C. city administrator Robert Bobb because the system was in financial disarray; or HUD Secretary Sean Donovan’s announcement that a dozen federal staff people in Detroit would work side by side with city staff on issues of housing, job-creation, and infrastructure as “Community Solutions Teams?” Note that the request for human resources was made by Mayor Bing himself, hardly shying away from the outsiders notion.

It should not be assumed that it is just the philanthropic foundations and the business-oriented Mayor Bing seeing the need to tap outside talent. “People [locally] have been doing this work for twenty years,” Smith of U-SNAP-BAC pointed out. “We need new sets of eyes, we need people to look at being creative.”

“I think that Detroiters should get more comfortable with outside guidance and best practices and other opportunities that are [from] outside of Detroit [and] that can be customized and implemented for revitalizing Detroit,” Detroit LISC’s Ziegler said. ”It’s all about how it’s done and the way it gets incorporated into the [local] process.” To an extent, even the foundations themselves are seen in some ways as outsiders in Detroit. But foundations have a potentially important and productive “outsider” role to play. As The Skillman Foundation’s Goss put it, bringing “what we have learned from other places that have done this right, that’s the role foundations can play.” The extra benefit, she noted, is that “philanthropy is stepping forward and offering resources and expertise [that] sometimes the public sector doesn’t have.” And sometimes can’t afford. Together with the mayor, foundations confront an entirely understandable problem in a city that has had the history of financial tribulations Detroit has had. As Living Cities’ Hecht suggested, “The challenge with Detroit is that [the City] . . . continue(s) to have less capacity than they need to meet their ambitions.”

New decision-making dynamics: The notion of public-private partnerships has become trite, but Detroit’s problems won’t be solved in the old manner. In years past, there was a corporate decision-making circle that would meet and, somewhat behind the scenes, make many of the large decisions for Detroit – and for their own benefit. Those corporations are gone, but left behind are the foundations whose capital was created by them. The decision-making dynamic is no longer one of corporate heads meeting in smoke-filled rooms but rather foundations trying to figure out how to deploy their philanthropic resources, and city officials trying to leverage and stretch their increasingly strained public dollars. Both sides have to get used to a new dynamic that is more open and collaborative, and which brings both sides to decision-making tables that may be more transparent and less risk averse than all parties are used to. One of the “outsider” controversies involved community participation. On all sides, the call has been for more action and less meetings-without-action. The city’s initial process for examining the land-use plans being generated for neighborhoods was a rather traditional public hearing, which devolved into the usual citizen gripe-and-complaint scenario. The foundations suggested moving forward with alternative and continuous participation mechanisms using social media as well as other online alternatives to the typical CDBG- and budget-type hearings of most municipalities. Hecht believes that Kresge’s push “to use modern technology [toward] new and enhanced civic engagement . . . [was the] biggest friction” in the fraying of some foundation-city relationships. Critics focused on the technological participation modalities as the issue, but they really weren’t the problem.

The real problem is that Detroit has to come to a new way of making decisions. The players must sit around a larger and more transparent table, and that is discomfiting for everyone. Hecht describes the challenge and discomfort as “the way change is coming up in the future, it’s distributed, it’s not the mayor in charge or Kresge in charge, [but] there is a robust multisectoral table that’s been built . . . a new civic infrastructure that looks very different than the old power bases.” Hecht summed it up as a “very different table, helping to define in the future.”

Things are different locally – in Detroit – and nationally due to what seems to be a change in the nature of the U.S. economy. Goss hypothesized that the fact that a different kind of decision making has to evolve in Detroit may be because “there’s so much economic disparity in our community and in communities across the country, people are feeling so much more vulnerable . . . maybe the stakes are just so much higher.” Why create a new, “distributed” form of decision making? Because“our ability to solve complex problems is broken, and we need to build a new way of solving them,” said Hecht.

For Rapson, the controversy reaffirms what he and other foundation executives ought to know about the communities they want to help through public-private partnerships. “The problems are so deep, the skepticism is so profound” in Detroit, Rapson said. Detroiters have good reason for their distrust and despair, having watched plenty of prescriptions for the city’s revitalization come to nothing. “Unless philanthropy is really clear about what it is doing, what its role is,” he added, “it can’t be held accountable.” Rapson and his peers have to recognize that the democratic process requires foundations, as he acknowledged, “to put our ideas into the public forum, [admit that] we can’t say we’re right, but we hope we’re influential.”

Overall, despite the Wall Street Journal’s hint that the foundations – or Kresge – were taking their dollars off the table, there’s not much evidence of this. What seems to be occurring are tension and conflict leading to clarification and change, but not philanthropic withdrawal or City Hall’s writing off of its foundation partners. As Goss told us, “I don’t think we always agree on strategy all the time, I think it’s pretty human that we disagree on how to get to the endpoint . . . [but] I don’t believe that it’s fractured.” Each side has way too much invested at this point to walk. Foundations like Kresge invested in land use issues or Skillman invested in youth and education “have to have a point of view of what the future of their place should look like,” said Hecht. “You’re not just a passive partner,” Hecht advised foundation excutives. “If you‘ve invested in that community, you have a point of view and you have to lead – not be theleader, but you have to be a leader.”

There’s no guarantee that the partnership between the foundations and the city will succeed in creating a new Detroit, but perhaps surprisingly, everyone we spoke to predicted success. As Ziegler sees it, “I think it’s going to have a positive outcome, we’re all going to be on the same page for what we’re going to need to do.”In a way, the foundations and the city government have no place else to go. “This is an evolving partnership,” said Ziegler. “Even though there’s maybe some tension, I always think that conflict is good because it helps bring out lessons quickly.” The foundations, politicians, and bureaucrats “need to adjust and change the way they’re looking at the work.” Indeed, if they do not, the outcome will be not a new Detroit but a continuation of the embattled, deteriorating Detroit of old.

The Kresge Foundation has provided grant support to the Nonprofit Quarterly in the past, and NPQ is currently under consideration for a grant.