One of the highlights of Boston’s recent mayoral election cycle was that John Barros and Bill Walczak, two well-respected nonprofit leaders, stood for the office. John Barros is the former executive director of the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative and the current economic czar for the City of Boston; Walczak is an activist and the founder and former longtime CEO of the Codman Square Health Center. But beyond the fact that both were nonprofit community leaders and mayoral candidates, they are also linked by having both been 2007 fellows in the Barr Foundation’s fellowship program. They are part of the leadership network that the foundation has created and supported with sabbaticals and rich common learning experiences. These experiences across subsector boundaries have created unexpected new ideas and collaborations among 48 of Boston’s most tireless, passionate, skilled, and opinionated leaders over the past six years. Barbara Hostetter, one of the founders of the foundation, says that the Barr Fellows program was originally conceived as a way to repay local leaders, but it has become much more meaningful over time as a way of connecting the dots.

|

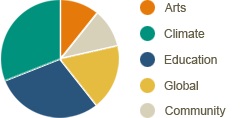

The Barr Foundation provides $60 million in grants annually to support work in the arts, climate, education, and community. Although they began with a Boston focus, some of their grantmaking has gone global.

|

But I write about the Fellows not only as a great network, but also as a welcoming committee of sorts to Barr’s new president and a potential group of very skilled guides.

In November, the Barr Foundation announced that it had selected its first president in James (Jim) Canales, who is well known and well respected for his leadership of California’s James Irvine Foundation and for his active leadership within philanthropy, both in California and nationally.

Still, the choice was a surprise. And, in case it needs to be said and is not achingly obvious to everyone in this sector already, the occasion of a new foundation president is anticipated with not a little anxiety. Nonprofits work very hard to make relationships with, get the ears of, or have some modicum of influence with foundation leaders. We have seen many instances of new presidents who dismantle staff, logic models, and partnerships in the blink of an eye upon being hired, leading one to wonder about the governance of the institution. But, you may say, perhaps the institutions needed a clean sweep! A different direction and a new point of view—not to mention, too often, a lot of new, indecipherable language. All well and good, except when all of that comes to relatively naught, only to be followed by another upheaval and maybe a mea culpa or two a few years later. This is tough on community groups, who often feel they serve at the whim of…

Barr’s two previous leaders were from New England; the most recent, Patricia Brandes, came from a long influential tenure at the United Way of Massachusetts Bay and Merrimack Valley. Pat’s legacy at Barr is an emphasis on networks and the Fellows program. But Canales is a lifelong West Coast guy, and here he is, moving to an über-East Coast city to take on the position of leadership in one of Boston’s largest philanthropic institutions. What is a hopelessly parochial city to think? Because the truth is that although Boston is a true gateway city with a rich mix of immigrants and even a cosmopolitan air in parts, it has a well-storied way of making many “outsiders” pay an emotional entrance fee.

|

The Foundation’s mission is to support gifted leaders and networked organizations working in Boston and beyond to enhance educational and economic opportunities, to achieve environmental sustainability, and to create rich cultural experiences—all with particular attention to children and families living in poverty. Sign up for our free newslettersSubscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox. By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners. |

The Barr Foundation was established fifteen years ago by Amos and Barbara Hostetter, and it currently has assets of around $1.4 billion. Amos Hostetter was the founder and CEO of Continental Cablevision. But when I met Barbara in the harborside offices of the foundation on a snowy January afternoon, there was little about her to indicate the trappings of wealth. Soft-spoken and straightforward, she admitted that the foundation was a young learner. In fact, she said that the family and the foundation have seen themselves as being on a steep learning curve where philanthropy is concerned, and that hiring Jim at this time was part of their plan to make the foundation more independent of them. She said, “We know and respect that what we have here is a lot of money. We want to do this right. I feel like the foundation is an adolescent entering adulthood and that it is time to take a very big leap.”

So, again, why Canales? The word that came up repeatedly in my conversations both with Jim and with Barbara was “humility.” She said, “Humility was definitely the connecting point. We had gone through a year of planning and started a search process and everything was progressing. Jim’s name kept coming up, but he indicated that he was not interested in the position. Then, when we were visiting our daughter in California, we decided to call him, if only to talk about our approach to the foundation’s evolution and the transition. But we had a wonderful conversation over lunch and ended up asking him to reconsider.”

Barbara described what happened next. “He said give me 24 hours, so we did, and when we called him back, he said give me two days, and then it was a couple of weeks, and then we came to terms.”

Hostetter said that it was his obvious humility and humanity coupled with his professionalism that sold them because they wanted a particular kind of very strong culture at the foundation—a culture that kept grantees at the center, a culture where respect for grantees was first and foremost and where partnerships with and between grantees sustained the work even when it was difficult and confounding.

When I spoke with Jim, he said he was excited to start a new journey at a new foundation and to be able to move to Boston with his partner, whose family lives there. Then he asked me, as we talked about how he would enter into what is essentially center-stage Boston philanthropically, “Do you have any advice for me as I start?” And that, in the end, is probably why the Hostetters, if they wanted a grantee-centric institution, a foundation that is both genuine and transparent, a foundation with great tolerance for risk, were so sold on Jim Canales. He would be wise beyond measure to tap the foundation’s assets in the intelligence and connections of the Barr Fellows as a start.

So we asked a few of the Barr fellows to grace us with their advice to Jim. Jesse Solomon of BPE wrote back to say that Boston is a relatively rich city in many ways, but its nonprofits do not always play well together. Boston, as you may know, is famous for its sometimes-prickly culture juxtaposed to an ability to pull it together from time to time in an extraordinary way (I am writing this on Marathon Monday). It is important to recognize that both things are true. Sister Margaret Leonard of Project Hope, with her usual humility, deferred from any advising because she has not yet met Jim. Margaret is a relationship master, a deep listener, an attacher of people to causes, to longings, and to each other. She would not presume to get ahead of the human aspect of that.

Vanessa Calderón-Rosado of Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción (IBA) wrote of her hope that Canales would get to know the neighborhoods of Boston. “The city is so rich in culture, in history and in wisdom. And often the contributions of the neighborhoods where regular people, particularly people of color, live are ignored and forgotten. He will have to establish many connections in the ‘big’ known circles of influence, but I’d argue that there’s enormous power and influence in the work of people in each one of Boston’s vibrant neighborhoods.”

And Bill Walczak summed it up this way:

Welcome to Boston, a city of contradictions. We’re a city of immigrants, but hold on to traditions that began with the Puritans nearly 400 years ago; we celebrate history, but also want to be the leading edge of innovation and new things; we are set in our ways, but have reinvented ourselves successfully several times in the past few hundred years; we both love and hate our renowned academic institutions; we hate New York sports teams but love the Big Apple; we have a lot of pride in what we are, but enjoy criticizing what we don’t like, and won’t tolerate the criticism from outsiders. Our nonprofits are among the most sophisticated you’ll find anywhere, but collaboration seems to be very difficult to accomplish. On the other hand, it is an area of tremendous pride, with people who want to be the best we can be, to solve the seemingly intractable problems that plague our society, and I think you’ll love being here (except in parts of January and February).

So in the end, we wish Jim the very best as he starts his important new job in our sometimes cranky but wonderfully complex city in May, and we look forward to seeing him around. And for our neighborhoods, we wish for a philanthropic leader who adheres to the idea that the intelligence and energy of Boston resides in the many more than in any elite, and who gets out into and hangs out in the neighborhoods. In the Barr Fellows, you have many bridges to the wisdom and riches embodied there.