In the Locked Out: Black Women, Wealth, and Homeownership series, members of Insight Center, Springboard to Opportunities, and several expert co-authors connect the lived experiences, hopes, and dreams of low-income Black women and their perspectives on homeownership to the historic and current policies that fuel our exclusionary housing market—and its impact on health and wellbeing—to advocate for equitable housing solutions for Black women.

Housing insecurity and its relationship to wealth inequality in the United States is not only an economic justice issue—it’s also an issue of racial, gender, and health justice. Black women sit at the intersection of these matters and, as a result, experience a tsunami of structural inequities that threaten their health. According to the CDC, being unhoused is “closely connected to declines in physical and mental health.”

In a moment where housing affordability and justice have become staple concerns in public discourse, understanding the overwhelming toll of housing insecurity on Black women’s health is vital. To fully address this issue, our solutions must center the health of Black women—and by extension, that of their families.

The Stress of Housing Insecurity

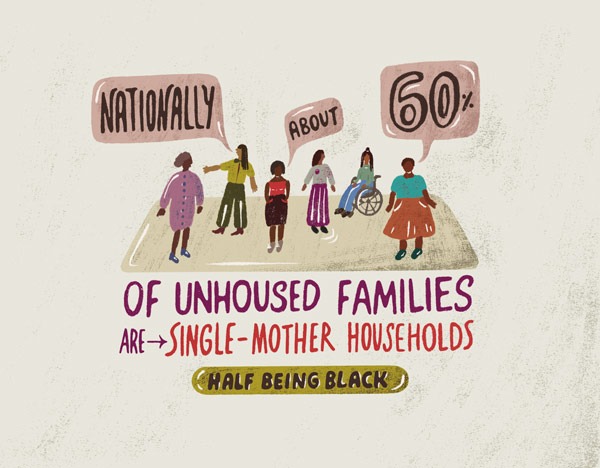

A home offers a sense of security, safety, and peace of mind. Conversely, not having reliable housing is a heavy emotional burden. Black women have the worst outcomes of any social group in all aspects of housing in the US; they face pervasive barriers to homeownership and high foreclosure risk, are disproportionately impacted by spiking rents and eviction, and are overrepresented in the country’s unhoused population. Over the course of their lifetime, Black women experience eviction at three times the rate of white women; one in five Black women will go through an eviction, compared to one in fifteen white women. Nationally, about 60 percent of families that are unhoused are single-mother households, with Black single mothers heading almost half of these households.

Make no mistake, though: the lack of wealth made available to Black women is the root cause of these disparities. Without a nest egg to draw from, Black women are automatically at a greater risk of eviction and becoming unhoused.

However, even Black women who accrue enough wealth to buy a home face compromising conditions. The foreclosure crisis that followed the Great Recession is a prime example of how the mortgage industry’s predatory lending practices targeted Black women who held assets. As noted in Monica Potts’s The Collapse of Black Wealth, not only did 240,000 Black families have their homes taken in foreclosure due to subprime mortgages, but Black families also lost value in homes they held onto, contributing to a significant drop in their wealth. In Prince George’s County, Maryland—a Black suburb outside Washington, D.C.—houses dropped in value by nearly $100,000 in 2009, a decline not seen in comparable white neighborhoods. This loss of wealth has deep intergenerational physical and psychological impacts.

Racially adverse outcomes also appear in the rental market, where they impact Black women in unique and disproportionate ways. In December 2021, 18 months after the Covid-19 pandemic began, roughly 31 percent of Black women were behind on their rent—nearly three times the rate of white women—a difference attributed to society’s tendency to push Black women into unreliable, poorly paid work.

According to this same data source, nearly 15 percent of Black women were behind on mortgage payments—again, more than three times the rate of white women. Unsurprisingly, research shows that foreclosures and mortgage distress increase depression and anxiety. Given this, even Black women who have overcome barriers to homeownership face profound mental health challenges.

Having little to no wealth to weather life’s storms, Black women who face housing insecurity—particularly those who are primary or sole caretakers of their families—experience a range of downstream effects. They are more likely to face income fluctuations or a loss of income entirely. Their children are more likely to experience educational disruptions and delayed development, and their families are more likely to experience negative health outcomes.

Forced to the Margins

Thanks to the segregation of Black people in polluted and otherwise hazardous areas through redlining, Black women must contend with the impacts of housing injustice on their health even after overcoming obstacles to homeownership. According to ProPublica, “the level of cancer risk from industrial air pollution in majority-Black census tracts is more than double that of majority-white tracts.” Black families already spend close to twice as much of their income on health insurance premiums than the average family, straining their ability to save and build wealth. Paying for illnesses caused by environmental hazards further jeopardizes their economic stability. Sequoyah, a Black single mom raising a daughter in downtown Atlanta, says: “It has always been important to me to live in a good environment. A good home is somewhere where you can feel safe, in a positive environment with good schools.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Meanwhile, soaring house prices continue to drive aspiring Black homeowners further away from historically Black neighborhoods and their communities. Shameka, a resident of downtown Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward, says the only person in her family to own a home is her grandmother, who had to move an hour and half outside the city to afford to purchase her house. Losing elders and longtime residents in a neighborhood with such a rich Black history—Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward was the birthplace of Martin Luther King’s church—is an incalculable loss that Shameka hopes to mitigate by keeping her family in place. As an aspiring homeowner, however, she faces a challenge: Atlanta’s rising home prices. “I love my city,” Shameka explains. “I love the convenience. I like the historic places and the zoo and everything that is convenient downtown. Every morning on the way to school my daughter is like ‘Mom, there’s the city!’ and I say, ‘You live in the city!’” Being close to the city and its resources is central to her and her daughter’s quality of life.

As the real estate adage goes, when it comes to housing prices, everything comes down to “location, location, location.” In major urban centers, historically Black neighborhoods are gentrifying rapidly, despite the hazards to which they’ve been disproportionately exposed. While Black families have lived in these neighborhoods for generations, even these polluted environs are becoming unaffordable for Black women—who must now contend with the mental and emotional stress of displacement on top of environmental racism’s impact on their physical health.

Housing’s Role in Racial Weathering and Pregnancy Outcomes

A lack of affordable housing is just one of multiple structural injustices that Black women face; they also face “racial weathering,” a term that researchers use to describe the wear and tear of stress on the body of racially oppressed people that leads to declining health and premature death. In short, constant interaction with a toxic social environment causes stress, which causes bodies to age more rapidly and makes them more susceptible to illness.

By creating an unstable environment, housing insecurity subjects Black women to a steady stream of toxic stressors, from daily racist microaggressions to financial and housing stress and physical violence, resulting in detrimental health and morbidity that impact not only Black women, but their families as well. Indeed, studies show that racial weathering impacts pregnancy and preterm birth outcomes. Black women are twice as likely as white women to give birth to a low-weight baby, and the infant death rate is 2.4 times higher for Black than white women.

A stable home is fundamental to a person’s physical and mental health and quality of life.

The Supreme Court’s decision to overturn abortion rights at the federal level will subject Black women to even more racial weathering and adverse pregnancy outcomes, further complicating their efforts to purchase homes. Black women reside in greater numbers in many of the Southern states that are legislating to ban abortion. Due to race-based economic and health inequities, Black women are four times more likely to have an abortion than white women. Women who are forced to carry an unwanted pregnancy to term experience profound economic impacts, with research finding that the $9,000 annual cost of raising a child increases the likelihood of evictions and bankruptcies. Outlawing abortion also puts Black women at a higher risk of dying given the US’s soaring maternal mortality rate, which could increase an additional 33 percent if conservative leaders are successful in their attempts to enact a total abortion ban. For all these reasons, the physical and financial risks associated with overturning Roe v. Wade make it even harder for Black women to purchase homes.

Home as Health

A stable home is fundamental to a person’s mental and physical health and quality of life. As Carol, a Black woman taking part in Georgia’s In Her Hands guaranteed income program, told us, “For me, it’s the most wonderful thing you can do to own your own home…it’s a peace of mind.” Black women have been denied this basic right, resulting in health harms. Changes to our housing system are long overdue.

In the next installment of Locked Out, we’ll interrogate the myth of the Black middle class and examine the dynamics that prevent Black women from building wealth in the same way as their white peers.