August 14, 2016; Juvenile Justice Information Exchange

An alarming article by Dick Mendel of the Center for Public Integrity and published in the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange places the regressiveness of the Arkansas Juvenile Justice system at the feet of what he terms “entrenched nonprofits.”

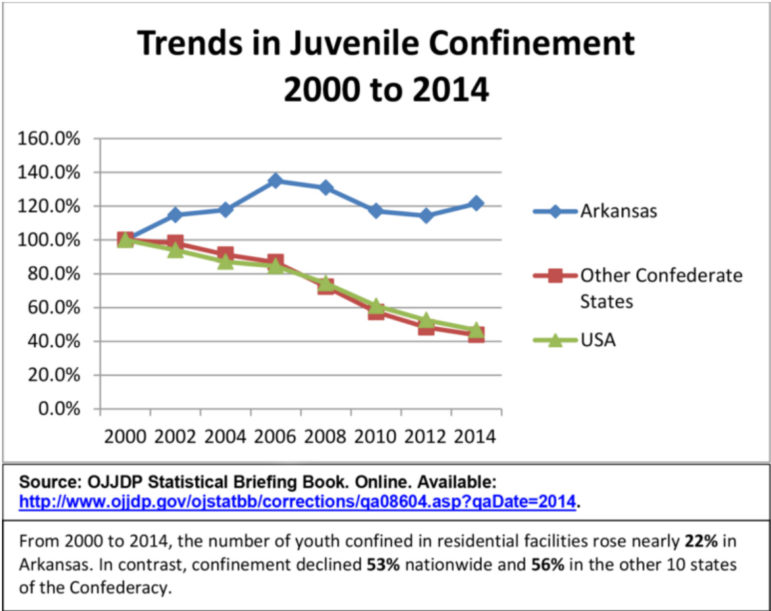

Mendel begins his article by showing that Arkansas has bucked national trends over the first part of the 21st century. From 2000 to 2014, the number of Arkansas juveniles incarcerated increased by 22 percent as the nationwide numbers declined by more than 50 percent—not only nationally, but among the ten states of the former Confederacy.

He continues by citing two reports documenting the conditions in the largest of Arkansas’ juvenile correctional facilities and the state’s trend toward jailing children for “status offenses” like skipping school or running away from home.

Mendel asks, “Why is Arkansas apparently moving backwards when many of its peers, including several deep red Southern states, have turned a corner by embracing more humane and evidence-based approaches to juvenile justice?”

The answer, he says, may lie in the outsized influence of Arkansas’ network of nonprofit service providers, which he describes as community-based and widely respected, with a long history of caring for troubled children. Many launched in the 1970s after the Runaway Youth Act made federal funds available for programs to assist wayward youth. They soon banded together to expand their influence, placing politically connected leaders on their boards and forming the Arkansas Youth Service Providers Association. From there, they “negotiated standard contracts with the Division of Youth Services (DYS) to pay them for community-based services, and some opened residential facilities as well. Rather than fight each other for funding, the 13 providers agreed to carve the state into pieces, and each became the sole recipient of DYS contracts in its given territory.”

Mendel writes that while no one accuses the providers of bad intentions, a number of observers say they are obstacles to real reform.

“The providers have become very entrenched,” explains Paul Kelly, who formerly ran a provider agency and was the first director of the providers’ association. “They very seldom have anyone competing with them,” Kelly said, saying also that they have fought “any really meaningful accountability for the impact of their services.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Ron Angel, who served as DYS director until 2013, said that the providers told him in their first meeting what was what. “They have been here for 30 years. […] They knew what was needed, and there was nothing that could be brought in that would work any better than what they were doing at the time.”

But at the time, DYS was dealing with lawsuits over abusive conditions in its main juvenile facility, and it turns out that 42 percent of the young people incarcerated had committed only misdemeanors. Angel subsequently implemented reforms and the number of young people in state custody fell slightly.

In 2013, Angel and his allies crafted legislation that would have established local Community Youth Services Boards, thus interfering with the insular world of the service providers. According to Mendel, the providers mounted a lobbying campaign against it.

John Furness, executive director of Comprehensive Juvenile Services in Fort Smith, Arkansas, is unapologetic about killing Angel’s proposal. “I saw that as a complete dismantling of the very established provider network that has been in place for many years and does good work,” Furness told [Mendel]. “I thought it was a bad bill, and we spoke out against it.”

Mendel also charges that the provider association blocked attempts to gather data.

When Angel tried to make service providers report details on the services they offered and their results, “you would have thought we had asked for their firstborn child,” Angel recalled. “How can you base your treatment if you don’t have standards where you can measure what’s being successful and what’s not?”

The dynamic, according to Mendel, has resulted in a rapid turnover of DYS directors. Angel was the agency’s ninth new director in 12 years, and the agency has had two more since with the latest one abruptly resigning.

Still, reports Mendel, there is a groundswell of interest in the field from politicians who see the need for change in the numbers. Mendel writes, “If they continue to resist, the providers will likely squander their credibility and lose their cherished place at the heart of the Arkansas system.”—Ruth McCambridge