June 9, 2013; The Gulf Times

Last week’s revelations about the massive data collection efforts of the National Security Agency, and yesterday’s self-outing of NSA whistleblower and former CIA employee, Edward Snowden, have generated lots of newspaper coverage, but somewhat less critical response by our nation’s leaders. A bipartisan collection of members of Congress have rallied around President Obama’s defense of the NSA’s PRISM program, with only a couple of voices—notably Rand Paul among Republicans, Jon Tester among Democrats—expressing qualms that PRISM might be an abrogation of innocent Americans’ Fourth Amendment rights. The prevailing dual theory of PRISM defenders combines the veiled threat that there are bad guys out to do harm to Americans who need to be tracked and intercepted and the platitude that if you’ve done nothing wrong, you shouldn’t worry that PRISM will find you have something to hide.

Steven Aftergood, director of the Federation of American Scientists’ Project on Government Secrecy, told the Gulf Times that since 9/11, surveillance like the NSA’s has become the norm. “One could say that personal privacy has been compromised for years, but we are only now becoming aware of it.” Elizabeth Gotein of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University expressed hopes that the news of the NSA program would serve, as the Gulf Times put it, “as a wakeup call for Americans,” but noted that President Obama’s apparent willingness for a public debate about this kind of surveillance is difficult when government agencies are already many years into their secret data collection activities. Marc Rotenberg, executive director of the nonprofit Electronic Privacy Information Center, suggested that “the system of checks and balances has collapsed,” perhaps referring to indications that the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act courts that approved 1,789 government applications for electronic surveillance and 212 applications to access business records may have never rejected a government application, something that is difficult to know, since the courts operate with great secrecy and the companies that are affected by the FISA courts are not permitted to reveal that they have been tapped.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Defenders of the NSA, such as California senator Diane Feinstein, herself the sponsor of legislation last year that would have been more draconian than the current NSA program, are quick to point out that it’s only “metadata.” In the context of telephone and e-mail communications, metadata is the pattern of communications—who sends and who receives and how much, not the content—but in many ways, metadata is much more important, in intelligence gathering terms, than trying to interpret the content of the messages. PRISM’s metadata sources include the servers of Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, Facebook, PalTalk, AOL, Skype, YouTube and Apple, according to the information published by the Washington Post and the Guardian, with Dropbox described as “coming soon.”

“We’ve crossed a digital Rubicon here; there’s no going back,” Jeffrey Chester, the executive director of the nonprofit Center for Digital Democracy in Washington, told the press. “Big data is ruling our lives, and the big question is whether there will be any kind of limits here, protecting our consumer information and our democratic right to privacy.”

Do you want to be assured of your electronic privacy? Regardless of the laws on the books or the proposals under consideration, the only real guarantee of online privacy, one former NSA expert observed, is “do not own a computer, do not power it on, and do not use it.”

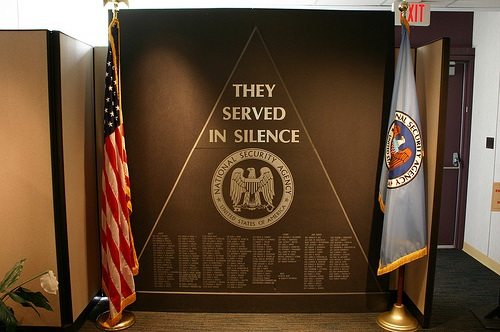

Are nonprofits concerned? Should they be? Is the Fourth Amendment imperiled by the NSA’s PRISM program and other mechanisms of domestic surveillance? Or is this simply the New (post-9/11) Normal, and part of the price we have to pay for living in a world of people who would cause as much destruction as they possibly could, were it not for the ability of the U.S. government to track them through secret programs carried out by agencies such as the NSA?—Rick Cohen