Stories about foundations serving rural America don’t often make it to the front page—or anywhere else for that matter—in national and regional newspapers. People living and working in rural America, however, know what access to philanthropic dollars means and sometimes how difficult it is for small, nonmetropolitan communities to access foundation support.

Mary Anne Davis, a member of the editorial board of The Union, the newspaper of western Nevada County in California, writes enthusiastically about the creation of the Penn Valley Cultural Center, which will house a 562-seat performance hall, a 5,000-square-foot library, a visitor’s center, meeting space for nonprofits, and a permanent art gallery. She credits the Penn Valley Community Foundation for this initiative while acknowledging that half the funding will be from a USDA Rural Development Program loan. The population of Penn Valley is 1,621; of Nevada County, 98,200.

In northern Idaho, the Panhandle Alliance for Education, a community foundation modeled on the Seattle Foundation, has been putting about $500,000 a year into the Lake Pend Oreille School District for teacher grants (for purchasing books, musical instruments, and classroom technology items), the hiring of a guidance counselor, reading and writing programs, plus a full-day kindergarten and instructional coaches. The district centers on the city of Sandpoint, population 7,577, the county seat of Bonner County, population 40,699.

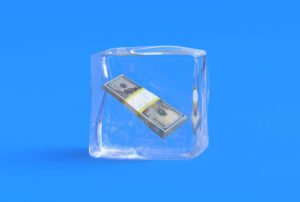

Community foundations like Penn Valley and PAFE exist largely due to the charitable generosity of local residents, but rural communities, particularly lower income rural areas, don’t often generate much in the way of community foundation assets. The result is frequently very limited charitable grantmaking. Unlike metropolitan areas, rural America doesn’t get much in the way of foundation grant support from major private foundations, a circumstance that USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack highlighted as a frustration in his comments at the National Rural Assembly in Washington last week.

Where are the major foundations? Where is institutional philanthropy in toto in response to the needs—and the opportunities—of rural America? That was the topic for four dedicated rural grantmakers at last week’s National Rural Assembly: Justin Maxson, the president of the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation in Winston-Salem, North Carolina; Kathy Annette, the president of the Blandin Foundation headquartered in Grand Rapids, Minnesota; Jamie Bennett, the executive director of ArtPlace America; and Heeten Kalan, a senior program officer of the New World Foundation. Their increasingly non-rural foundation peers have much to learn from their insights, summarized below:

Why so little rural philanthropy—and why is it declining even further?

New World’s Kalan suggested that one of the problems is that philanthropy follows demographic shifts. With more movement and attention to metropolitan areas, rural falls prey to the foundation sector’s obsession with metrics—there are more people in metropolitan areas, thus foundation money for metro projects yield bigger numbers even if the meaningful impact may be much less than the headcount. However, Kalan turned the argument around in an interesting way, suggesting that if grantmakers are aiming to change federal policies, with the demographic shift toward urban, they focus on urban to the detriment of rural.

Annette suggested that part of that problem is not just counting numbers, but vision. She suggested that the vision for rural America—and for rural foundations and nonprofits—has not been well articulated to Blandin’s peer foundations. ArtPlace America’s Bennett suggested that the narrative is that rural communities are “broken” and need to be “fixed.” It is a negative narrative, underplaying or missing the models and opportunities in rural communities that can and should be recognized as valuable for the entire nation, rural and otherwise.

Getting foundation staff into rural communities

The wrong-headed rural narrative may reflect a limited willingness of foundation program officers to go to and experience rural communities for themselves. Kalan said that New World puts a large emphasis on fieldwork, spending time with people where they live, including rural areas. He offered that he didn’t think a lot of other foundation people did that, meaning that they missed understanding both rural struggles and rural strengths. Maxson said that the key is for foundation staff to understand “place” and “context.” Without that, he suggested, it is going to be difficult to move foundations toward more rural grantmaking.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Pressure from within and without

Surprisingly, all of the foundation discussants were somewhat at a loss to think of venues where rural funders could organize and promote their collective vision. Annette mentioned her commitment to build relationships with other funders and simultaneously shake things up. As a member of the board of the Minnesota Council on Foundations, Annette described her role as to specifically ask rural questions of her foundation peers. Bennett added that the role should also be to give rural projects a national spotlight so that other foundations might see opportunities to emulate or replicate.

While foundation execs might be able to buttonhole their peers in various foundation-focused meetings, the onus is also on rural nonprofits to be their own advocates. Maxson suggested that funding rural nonprofits to be advocates, to make the case for rural, should be part of the rural philanthropic agenda. Annette added that funders like hers can provide things beyond grants, such as leadership development and opportunities for rural nonprofits to meet and organize. Not many foundations, even those focused on rural, see funding rural self-advocacy as their role, but they might need to in order to move the philanthropic needle.

What is the kind of philanthropy rural communities need? Sometimes, it isn’t to replicate the proven, but to invest in untested ideas, according to Maxson, and sometimes that comes not from investing in projects but through providing long-term, sustained operating support. At Blandin, operating support appears to be the norm, with an opportunity for truly supporting high-risk ideas and groups.

Bridging the rural/urban divide

Overall, the advocacy for more rural grantmaking doesn’t go very far if it is seen or pitched as “more rural, less urban.” The challenge, therefore, is to bridge the urban/rural gap. Bennett’s ArtPlace America doesn’t just fund in rural communities, but he suggests that it is important for rural groups to be part of “everybody” conversations on income inequality, climate change, and other issues. However, they should aim to be overrepresented in those discussions—as opposed to the likely underrepresentation that currently exists. That might mean for rural funders a role to fund rural groups to attend those multi-sectoral or cross-geographic meetings, so that rural is present, visible, and heard.

One example of the problem might be in the work of some foundations to stop coal power plants. As foundations have come to grips with the need to find strategies that do not support carbon-based polluters, they must also remember they have an obligation to work in the communities where the coal comes from—or used to. Climate change funding comprises the need to reduce the nation’s overuse of coal power and paying attention to the conditions of the coal-producing communities. Some urban funders might not automatically get that.

Nonprofit capacity in rural America

Too many foundations believe that the reason for the lack of grantmaking in rural America is that there are too few organizations with capacity. Maxson pointed out that that is obviously “bunk”; there are incredibly strong organizations in rural communities. Bennett suggested that we stop using the word “capacity,” calling it a “lazy word” that lets funders off the hook for assessing what an organization really needs to have or show. The generic coded language of “capacity” camouflages what organizations have to offer as the ability to receive and deploy foundation grant support effectively and productively.

So what can rural nonprofits do? Lead with ambition, says Maxson. Build relationships with other organizations dealing with parallel issues and challenges, suggests Kalan. Don’t be shy, according to Annette, suggesting that rural nonprofits have to be speaking more forthrightly to funders about what they want and need. In sum, it is a message for rural nonprofits to be more than supplicants, to develop a sense of self in which they speak to institutional philanthropy about rural needs, but more about rural opportunities for foundation grant support.

Ultimately, rural nonprofits have to be tougher and stronger with their foundation partners. Philanthropy gets too much of a free ride from nonprofits. We’re all tough enough with government agencies when it comes to advocacy. With foundations, nonprofits lose their voices, as though the only words possible were “please” and “thank you for your generous support.” With foundation support for rural America on the decline, the time for rural nonprofits to include foundations as a target for rural vision, education, and advocacy is now.