President Obama rectified an historic mistake this week. He awarded the Medal of Honor to 24 veterans from the Vietnam War, the Korean War, and World War II. All of these veterans had been denied the medal not because they were unqualified, but because they were African-American, Latino, or Jewish. Twenty-one of the medals were given posthumously.

It’s a sad reminder of the persistence of racism in the U.S. that it took a law passed in 2002 for Congress to review Jewish, Latino, and African-American veterans who had been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross to uncover these 24 heroes who had been denied the nation’s highest award due to nothing more than prejudice.

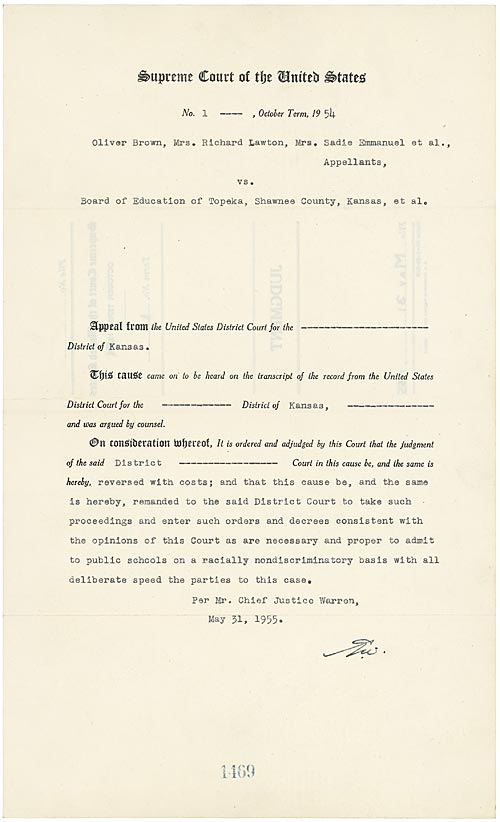

Sixty years after Brown v. Board of Education, fifty years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and forty years after Hank Aaron withstood racial threats while surpassing Babe Ruth’s homerun record, racial issues are still being confronted and, with difficulty, overcome in this nation. Despite electing Barack Obama the nation’s first black president, the U.S. continues trips and stumbles over racism both overt and much more subtle.

Calling out overt racism

The overt stuff is the material of press headlines. It is easy to understand, though unfathomably difficult to still eradicate. The report from lawyer Ted Wells for the National Football League regarding Miami Dolphins lineman Richie Incognito’s vicious harassment of teammate Jonathan Martin exposed Incognito’s oddly tolerated use of racism in hazing and bullying Martin and others. There is no need to count and repeat Incognito’s frequent use of the N-word toward Martin, though Incognito dredged up other racial epithets for his teammate such as “liberal mulatto bitch,” “stinky Pakistani,” “shine box,” and “darkness.” Despite the barrage of racial taunts from Incognito and apparently two other linemen, the Wells report suggests that Incognito and others were not stopped by the team, or even their peers.

Perhaps because Incognito is a 6’3”, 319-pound lineman, the public dismisses his actions as simply locker room behavior. But sports are hardly the only venue for virulent racism. For example, a Republican state senator from South Dakota recently suggested that businesses should be allowed to discriminate by race, because the free market would deal with the problem in the end: “If someone was a member of the Ku Klux Klan, and they were running a little bakery for instance, the majority of us would find it detestable that they refuse to serve blacks,” said state senator Phil Jensen, better known as the author of a bill, fortunately defeated, that would have sanctioned discrimination by sexual orientation. “In a matter of weeks or so that business would shut down because no one is going to patronize them.”

Perhaps this Arizona state representative thought that a roast of Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio sanctioned overtly racist humor, but much of it was difficult to write off as funny. “Going out with Sheriff Joe is always an adventure,” said state representative John Kavanaugh. “Because when we go into a restaurant, most of the wait staff and cooks jump out the back window—and when they don’t, I never know what the hell is in my food.”

A state legislator from the suburbs of St. Paul, Minnesota, took to Twitter for his distinctive approach to race. “Let’s be honest,” state representative Pat Garofalo tweeted recently, “70% of teams in NBA could fold tomorrow + nobody would notice a difference w/ possible exception of increase in streetcrime.” He reluctantly apologized thereafter.

Parading the likes of Garofalo through the press until they own up to the stupidity of their social media usage is one way to deal with overt racism. Instances of covert racism—of racism in the policies and practices of business, government, and other institutions—are often more difficult to spot, more difficult to figure out how to address, and stubbornly resistant to change. While no one should assume that nonprofits and foundations are in any way immunized against racism due to their 501(c) tax status, there is a special role for nonprofits and foundations to play in taking the lead in attacking and exposing both overt racism and the less obvious but more pernicious manifestations of racism embedded in our society.

Calling out less overt racism

Take one of the most recent examples from a conservative politician who really should know better than the likes of Garofalo, Jensen, and Kavanaugh. Wisconsin Congressman Paul Ryan, former vice presidential candidate on Mitt Romney’s ticket, was recently interviewed on the syndicated radio show of former Secretary of Education Bill Bennett. It was an appearance Ryan may well regret. Explaining his theory of poverty, Ryan told Bennett that there is a “tailspin of culture, in our inner cities in particular, of men not working and just generations of men not even thinking about working or learning the value and the culture of work.” Adding a veneer of academic support, Ryan added, “Your buddy Charles Murray or Bob Putnam over at Harvard—those guys have written books on this, which is—we have got this tailspin of culture.”

Perhaps Ryan’s learning curve is a little limited, because he launched into this quasi-academic analysis of the culture of poverty after having joined Bob Woodson, the founder of the National Center for Neighborhood Enterprise, not long ago in a number of listening tours of inner city neighborhoods to better understand poverty and its solutions. Woodson responded to Ryan’s self-described “inarticulate” comments with the observation that Ryan has been spending too much time listening to conservative scholars who are only “passionate about the failures of the poor.” It would seem that even having been joined by Woodson, who brings a long and extensive history of fighting inner city poverty—from a conservative political perspective, it should be added—Ryan somehow didn’t absorb Woodson’s thoughts, but those of Murray, the author of The Bell Curve.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Nonprofits in health, education, employment, and more have the dual responsibility of calling out both overt and covert racism in all of its manifestations, especially at the local and regional levels where many of the examples of racial disparity remain to be confronted. For example, in Northeast Florida, pre-term birth rates are still much higher for black babies; the groups on the front lines of dealing with this are nonprofits such as the Northeast Florida Healthy Start Coalition, Jacksonville Community Council, and Healthy Baker.

When it comes to women with breast cancer, black women are 40 percent more likely to die than white women, even as mortality rates for white women with breast cancer have been declining in recent years. While the disparity in mortality rates is a national issue, documented by research conducted by the Avon Foundation for Women and the Sinai Urban Health Institute, it is particularly acute in such metropolitan areas as Dallas, leading to the creation of new groups such as Survivors on Purpose in the Dallas area. It also poses new challenges to existing organizations, especially in those cities where the disparity is worst; topping the list of 41 cities studied for racial disparities in breast cancer mortality (35 saw the disparity increase during a 20-year period) was Memphis, Tennessee.

A similar finding of sharp racial disparities emerges from a report of the Discipline Disparities Research-to-Practice Collaborative on school suspension rates. African-American students and students with disabilities are suspended from school at “hugely disproportionate rates” according to the Collaborative, which is funded by Atlantic Philanthropies and the Open Society Foundations. According to the Washington Post, the “gaps in suspension rates are not result of disparate rates of misbehavior…[but were attributable to] many other possible factors at work…[including] classroom management, diversity of teaching staff, administrative processes, characteristics of student enrollment, school climate.” While the problem is national, many of the solutions that show promise are more regional or local, such as the use of restorative justice practices in Denver schools and the adoption of threat assessment guidelines in Virginia schools.

Extraordinarily rare are efforts to address racial disparities in employment, as the nation as a whole has been stymied about addressing unemployment in general, but the evidence seems to show that despite national inaction, local nonprofit efforts are attempting to make changes. In Dane County, Wisconsin, where racial disparities in employment are severe, efforts such as Operation Fresh Start, the Nehemiah Community Development Corporation, and the Urban League of Greater Madison joined together in a collaboration called Project Big Step to get people of color into union construction jobs taking advantage of the area’s real estate construction boom.

Taking action against overt and covert racism

“Here in America we confront our imperfections and face a sometimes painful past,” President Obama said at the Medal of Honor ceremony. “So with each generation we keep on striving to live up to our ideals of freedom and equality, and to recognize the dignity and patriotism of every person, no matter who they are, what they look like, or how they pray.”

Trying to draw out lessons about how the U.S. might rectify these historical wrongs is fraught with problems, as the nation has been so obviously unsuccessful in many areas to date. The examples of the overt racism of Garofalo, Jensen, and Kavanaugh and the racism embedded in our society that shows up as racial inequities in education, health, and employment suggest some directions that are hardly new, but continue to merit attention.

While overt racism needs to be called out at all times, in some ways it is easier to isolate. Although Sheriff Arpaio may have decided to defend Kavanaugh’s attempt at humor, in most of these instances, Kavanaugh and his ilk are embarrassments even to others who share their own ultra-conservative political ideologies. Nothing excuses their racial comments, but nonprofit institutions have to speak up about what their racially intolerant and discriminatory sentiments mean. No one can sit on the sidelines, there are no “that’s just their opinions” explanations, there is no avoidance of speaking out if the language affects the operations and identities involved (such as the NBA’s Minnesota Timberwolves, which was hardly aggressive in denouncing Garofalo’s Twitter witticisms.)

More difficult are analyses like Ryan’s, which look like they are cloaked in less virulent racial attitudes but reveal themselves as biased and ill-informed just the same. That is the importance in conservative circles of people like Woodson. His constant efforts to educate people like Ryan—apparently unsuccessful in this instance—and to call out fellow conservatives on race are not to be minimized. “The greatest challenge facing the nation is how we treat the least of God’s children,” Woodson has said. “The challenge we face as conservatives is what is our solution to this problem.” Responses to Woodson seem to be little more than more mythology about the self-defeating failures of the poor.

While Jensen (who moved from Kansas to South Dakota to join in an effort to defeat Tom Daschle) is likely to be limited in his future public policy influence, people like Ryan are not, and to the extent that they function with influence in American politics, they have to be called out. “If we want to be credible to the public,” according to Woodson, “we should demonstrate how embracing [conservative] principles has a consequence of improving the quality of life for these people.” Ryan and others who cloak themselves as above the likes of Jensen and Garofalo should heed Woodson’s words.

Most difficult, however, is the embedded racial disparities in the way many institutions and many policies function. While some of these policies and practices might be layered with subtle racial animus, particularly issues of employers reluctant to hire African-Americans or school administrators all too willing to suspend or expel students of color, in many cases there may be little or no racial animus but still “hugely disparate” results like those uncovered by the Discipline Disparities Collaborative. For example, the persistent disparities in birth outcomes for blacks cannot be ascribed to something genetic about black mothers; studies show that the clearest causes are the sharply worse socio-economic conditions faced by most black families. Eight percent of black pupils in the St. Paul schools and seven percent in the Minneapolis schools are classified as having a “behavioral disorder,” which may be as attributable to the prevalence of zero-tolerance practices and cultures in schools as to overt racism, and correctable with the kinds of teacher training and positive discipline practices that are being advocated by U.S Attorney General Eric Holder.

Identifying and excising the worst overt racists in the education and health systems won’t overcome the persistent racial inequities that nonprofits see all the time among their constituents. The policies and practices that lead to racial inequalities are deeper, more embedded, and resistant to policies that would simply replace a racial malefactor with someone more benign. Nonprofits have to design as well as advocate for the kinds of changes that alter these racial disparities. We are all very good at identifying and researching the existence of disparities, but much less adept at fashioning responses and solutions. That is why so many well-intentioned efforts end up producing glossy studies and “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” programs.

This, then, is the challenge for nonprofits and their foundation supporters: calling out racists in public life, calling out political positions that are thinly veneered racial stereotyping, and calling out—and acting against—racial disparities in all walks of life.