August 6, 2019; Washington Post and New York Times

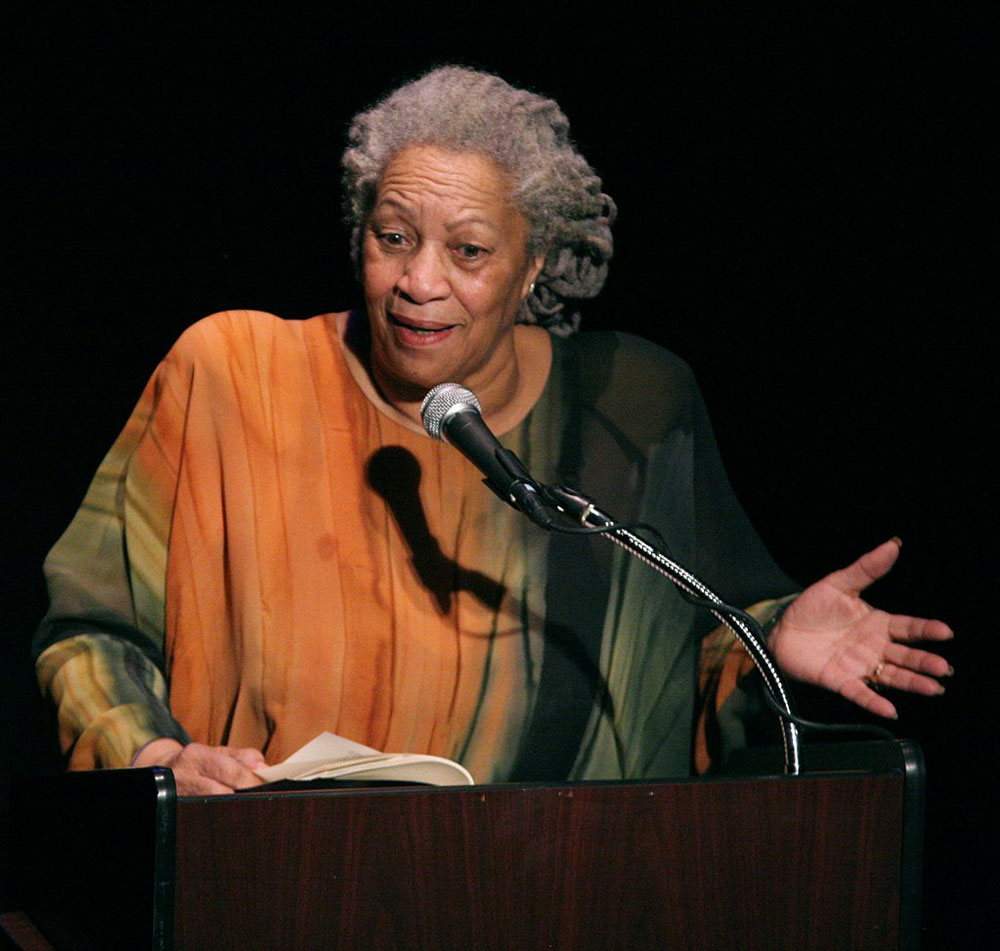

In a publication like ours that seeks to offer framing and narratives to help us reconceptualize the world around us, it seems apt to recall the life of Toni Morrison, one of the greatest narrative builders our country has ever known. If one were to stick to her oeuvre of writing—including such standout novels as The Bluest Eye, Sula, Song of Solomon, and Beloved, to name a few—that led her to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993, making her one of only two native-born Americans to do so in the past half-century, that would be sufficient to make this point. Washington Post book critic Ron Charles notes that with Beloved, Morrison, “the granddaughter of a slave…wrote the novel that definitively dismantled a century of Southern romanticism.”

Charles adds:

And most dramatically, she called forth the spirit of trauma that still haunts this nation, what she once called “the tenacity of racism.” Recalling the true story of Margaret Garner, an African American woman who killed her own daughter rather than allow her to be dragged back into slavery, Morrison presented America’s “peculiar institution” in terms so visceral and intimate that no reader could endure it unshaken. It was the greatest love wrapped in the greatest horror.

Morrison’s novels, in short, speak for themselves and will for generations to come. Yet her influence extends far beyond the novels she wrote. Rather, she sought to build the field of literature and give voice to Black women writers, both as a scholar—at different times in her life, she taught at both Princeton and Yale—and as an editor at Random House.

“There are writers that we would not know had she not been in that very crucial position as a black woman in publishing,” observes Angelyn Mitchell, a professor of English and African American studies at Georgetown University. Emily Langer, in her Washington Post obituary, adds that “Morrison also helped anthologize the writings of African authors including Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka. She oversaw the publication of The Black Book (1974), a best-selling documentation of Black life in America that included advertisements for the sale of slaves, photographs of lynchings, and images of churches and other spiritual places that had helped sustain black communities.”

Speaking earlier this year at the Boston Public Library, Angela Davis cited the influence of Morrison as the editor who first published authors like Toni Cade Bambara and Gayl Jones, as well as the autobiography of Muhammad Ali. Davis added that Morrison persuaded her to write her autobiography, something Davis was reluctant to do at 28, and later edited her book on Women, Race and Class.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“Today, US literature is not imaginable without the impact of Toni Morrison,” Davis remarked.

Broadly speaking, Morrison aimed to build a community of writers and to change the canon of what counts as US literature. In a 1981 address, she stated her goal this way: “We don’t need any more writers as solitary heroes. We need a heroic writer’s movement: assertive, militant, pugnacious.”

Morrison succeeded at opening up the canon to writers of color, and yet the power structure in publishing remains heavily white. A few years ago, in a profile of Morrison, Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah in the New York Times noted, “When African Americans represent an estimated one percent of those working at the big publishing houses, when women and writers of color have to track how seldom they are given chances to tell their stories and when the publishing industry fails to support or encourage this generation’s writers of color in any real or meaningful way, a dangerous reality is possible. What will happen to the next generation of authors who are writing from the margins?”

Morrison was hopeful that narrative could empower, but she was not blind to the use of language to undermine. A passage from her 1993 Nobel laureate address could have been uttered yesterday:

Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge. Whether it is obscuring state language or the faux-language of mindless media; whether it is the proud but calcified language of the academy or the commodity driven language of science; whether it is the malign language of law-without-ethics, or language designed for the estrangement of minorities, hiding its racist plunder in its literary cheek—it must be rejected, altered, and exposed…

Sexist language, racist language, theistic language—all are typical of the policing languages of mastery, and cannot, do not permit new knowledge or encourage the mutual exchange of ideas.

Morrison did go on to observe, more hopefully, that, “The vitality of language lies in its ability to limn the actual, imagined, and possible lives of its speakers, readers, writers…it arcs toward the place where meaning may lie.”—Steve Dubb