November 14, 2019; Chalkbeat

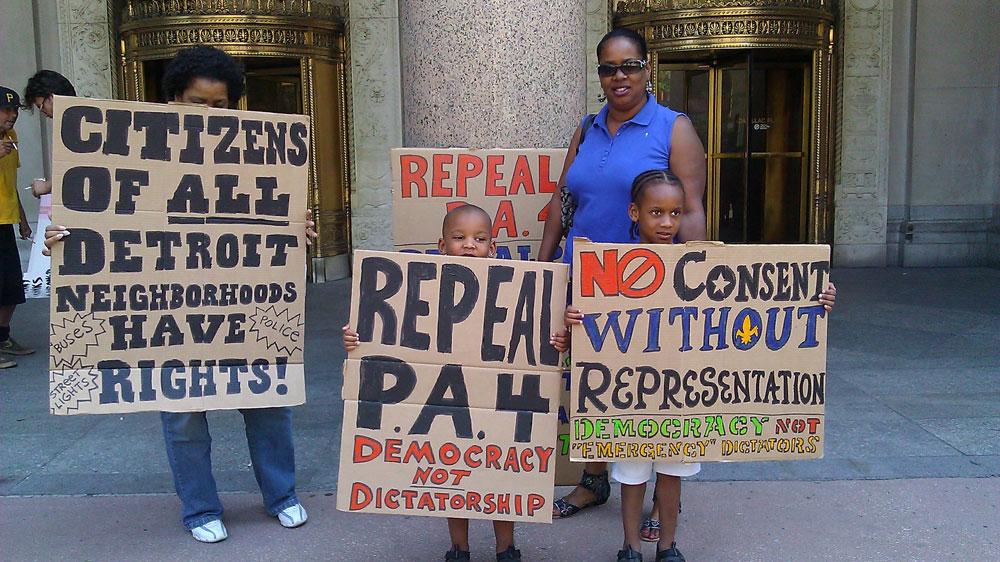

Like those in many Rust Belt communities, Detroit’s schools struggled to cope with the impact of declining population, falling property values, and insufficient state funding. In 1993, poor academic results and a deficit-plagued budget induced the state of Michigan’s white, Republican leadership to step in and take charge of the city’s schools, which served a predominantly black community. This was part of a larger trend of state officials in Michigan seizing control from local governments. At one point in this past decade, about half of the state’s black population was under emergency management and thus denied the right to elect their own local government.

The state’s so-called solution ignored the larger systemic issues that plague many urban school districts. The Michigan state formula for making things better was firmly based on the allegedly ability of state leaders to bring to bear managerial and educational competence beyond the capability of local leaders.

The same thinking, by the way, was at play when an emergency manager was sent into Flint. That manager made the fateful decision to source the city’s water from the Flint River, causing lead to invade the system. In fact, that manager, Darnell Earley, had also been the emergency manager for Detroit’s schools after his stint in Flint. In the newswire we wrote then, we observed that the state tended to use the emergency manager law in poor communities, resulting in an abrogation of voting rights.

After decades of responsibility over the education of Detroit’s children, in 2016, Michigan began to step back and return control of the district to a local school board. The newly elected board quickly commissioned a study of their current situation. Earlier this month, that report was received, and we now know how badly the state did and how ineffective its approach to educational improvement was. State control left the district with decaying facilities, a still limited budget, and no educational gains.

According to Chalkbeat, the study’s findings depicted the current situation in ominous terms: “The legacy of emergency management coupled with the continuing effect of inequitable school funding, will inevitably cause the district to hit a ceiling and impede its current progress toward a complete turnaround of traditional public education in Detroit.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Additionally, the report produced by the Allen Law Group found little evidence of effective management. Rather, they found the district had been left with the results of many avoidable, costly errors, which included “the purchase of overpriced real estate without proper due diligence” and “inattention to aging building maintenance.”

Perhaps most surprising is that the cadre of state-appointed leaders failed to even accomplish their purported primary task of addressing [Detroit Public Schools’] fiscal challenges. Instead of taking advantage of their relative isolation from the political pressures that supposedly hindered the ability of previous elected school boards, state-appointed leaders seemingly failed to make the hard decisions necessary to right-size DPS in a responsible and transparent fashion. Under state-appointed leadership, DPS engaged in questionable financial tactics and implemented temporary fixes, which allowed its debt to grow and ultimately led to the decline of DPS.

The educational failings are as dire. According to the report, “countless students throughout the city of Detroit who were likely not afforded the educational opportunities they needed and deserved.” As NPQ recently reported, the situation is so bad that students found it necessary to go to court demanding that their right to a quality education be honored. One of the plaintiffs in the suit “called school a ‘waste of time,’ explaining that his high school classes were taught from books meant for elementary students.”

When state houses take control of local school districts, the public rationale, at least, is always to benefit children and hold schools accountable for their performance. Just listen to Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner as he proposed to take over Chicago’s schools: “I want to protect the schoolchildren and their parents; that’s my first duty.” Or Ohio governor John Kasich describing his takeover of Youngstown’s schools: “If you’re a school district that’s failed year after year after year, someone’s going to come riding to the rescue of kids.” But beneath that, it is actually about race, politics, and ideology. The assumption that state leaders, who are predominantly white, know better than local black leadership is inherently biased.

The refusal of those who wish to wipe aside local control of school districts to confront the large, systemic problems of poverty and race dooms their efforts to failure. The belief that good management skills, even if the state were able to provide them, are sufficient is also mistaken. Tom Watkins, who was state superintendent from 2001 to 2005, told Chalkbeat there was “little hope of improving the district’s financial situation simply through effective management—not without solving underlying issues with declining enrollment and Michigan’s school funding structure. ‘It’s like trying to bail out a sinking yacht with a thimble.’”

Detroit reminds us of the inherent dangers of states taking control of local districts. It should be no surprise that supposed solutions imposed from outside often fall short. It is an old lesson, but it is worth repeating here: much more often than not, community members themselves are the best architects to design the solutions to the challenges they face.—Martin Levine