October 7, 2020; Guardian and Reuters

The Guardian is a 199-year-old news service that started in the UK. In 2019, the Guardian made an environmental pledge to, among other things, report on the climate crisis and its effect on people, the natural world, scarce resources, and economic structures. They pledged to achieve net zero emissions by 2030 and to stop accepting advertising dollars from fossil fuel extraction companies for all their formats. This week, they evaluated their progress over the last 12 months and renewed their pledge.

It turned out to be a timely commitment, with the arrival last winter of the deadly COVID-19 pandemic. The Guardian published pieces about the links between losses of habitats and biodiversity and the probability of more pandemics. In fact, since 2019, the Guardian has published nearly 3,000 environmental stories, opened by almost 100 million unique readers, based on scientific facts and without explicit political interest.

And there was a lot to cover in just 12 months. Reporting on marginalized communities, whether that means flooding farms in Bangladesh (made worse by rising sea levels) or the water crisis in the US, is part of environmental cognizance. There were also record-breaking wildfires in Australia and the western US, shrinking ice and glaciers in the Arctic and Antarctic, continuing school climate strikes, and the rise of Extinction Rebellion.

The Guardian’s pledge is critical in informing communities in order to create strategies to fight climate change. The news service continues to “report on how the environmental collapse is already affecting people globally” and “update global indicators that point to the urgency,” offering a dashboard of current data. The Guardian has also done an emissions audit of their operations, all the way down the supply chain, with the upshot being that they will eliminate two-thirds of emissions by 2030 and will participate in carbon offsetting for the other third. They’ve also eliminated more than 95 percent of investment exposure to fossil fuels.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The Guardian is committed to transparency and accountability in this process, too. They have become the first major news organization to become a certified B Corp, which means they are legally required to “consider the impact of their decisions on their workers, customers, suppliers, community, and the environment.”

The Guardian’s editor-in-chief, Katharine Viner, promised to continue raising the alarm on the climate emergency in a letter to readers. She emphasizes that “so many of our global problems—public health, migration, food security, land conflict, equality, gender and race—intersect with our environmental catastrophe.”

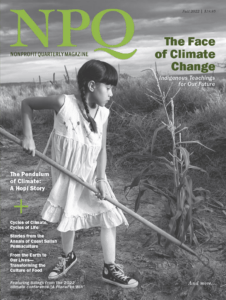

Continuing, she notes that Guardian reporting has shown the links between high air pollution and the COVID-19 infection rates. Such reporting has increased awareness that global heating disproportionately damages communities of color. What’s more, the Guardian has invited in guest editors, such as their special climate edition in September with seven first-time voters—Generation Z environmental activists from diverse backgrounds—to bring attention to the burden they will bear because of the neglect of the natural world by previous generations.

Independent, expert journalism can make a difference. It generates awareness of problems as well as the solutions. It galvanizes protest and resistance, putting pressure on government and industry to make positive changes. And it promotes and encourages best practice, human ingenuity and innovation that we can all learn from.

As Christiana Figueres, UN climate chief in 2015 when the Paris deal was sealed, told the Guardian’s environmental editor, Damian Carrington: “Without the work of the Guardian, the delivery of the Paris agreement would have been far harder or perhaps even impossible….At a time when the darkness of fake news and doubt in science is everywhere, the Guardian is a point of light.”—Marian Conway