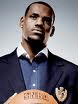

Are you sick and tired of the LeBron James spectacle? We are too. But not because LeBron didn’t have the right to leave the Cleveland Cavaliers for the talent-rich Miami Heat. To the contrary, he can do what he wants to do, even if he and his colleagues Chris Bosh and Dwayne Wade may well have cooked up their free agent ragout together two years ago.

Are you sick and tired of the LeBron James spectacle? We are too. But not because LeBron didn’t have the right to leave the Cleveland Cavaliers for the talent-rich Miami Heat. To the contrary, he can do what he wants to do, even if he and his colleagues Chris Bosh and Dwayne Wade may well have cooked up their free agent ragout together two years ago.

Our concerns, on the other hand, were the connection of the “LeBron Show” to journalism and to charity. On journalism, there’s little to say. ESPN’s three-hour spectacle reached for the nadir of journalism. Yes, sports journalism is supposed to be real journalism, but instead ESPN went for the audience, with interviewers Jim Gray and Michael Wilbon pitching softball questions to the superstar, creating more reality television than news event.

On the question of charity, it’s a little more complicated. James made his announcement from the Boys and Girls Club in Greenwich, Conn. Greenwich? James is from Akron, Ohio and until last week was employed in Cleveland, Ohio, both struggling rust belt cities. He’s relocating to Miami, one of the poorest cities in the nation. The connection to Greenwich is beyond us, unless there was some ESPN-based reason—the corporation is headquartered in Bristol, Conn., only 57 miles away.

Even so, couldn’t he have chosen a location someplace other than one of the richest cities or counties in the U.S. one press wag joked that the Greenwich Boys and Girls Club might be the only one in the nation with its own polo team. James could have chosen the Club in nearby Bridgeport, a desperately poor community consistently in and out of municipal bankruptcy.

Even if we can’t fathom Greenwich, we can understand the Boys and Girls Club. The numbers aren’t clear, but the LeBron announcement show was intended to raise as much as $2.5 million for the Boys and Girls Clubs nationally. All of the ad revenue sold from the show, estimated between $2 and $2.5 million, will go to the Boys and Girls Clubs of America (BGCA), plus additional donations from the University of Phoenix, Nike, and Sprite .

In fact, James’s representatives said that his motivation for the show wasn’t self-promotion or anything other than charitable. Others didn’t quite buy it, though. One CBS commentator suggested that the donation of the ad buys to the BGCA wasn’t “magnanimous…(but) guilt money…James trying to win the P.R. campaign, blunting the blow of this blatant ego boost by hiding behind a charitable cause.”

The BGCA CEO, Roxanne Spillett, played along, however, gushing about James’s generosity: “We were thrilled to hear from LeBron’s organization over this past weekend with this most generous gesture. Taking time out of what I am sure is a most difficult decision, and creating an opportunity for our Clubs and members to benefit, is just tremendous.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The Boys and Girls Clubs of America isn’t just any old charity. Like some other large national nonprofits like the American Red Cross, the United Way, and the Nature Conservancy, the BGCA has encountered its share of recent controversy. The very influential nonprofit paid Spillett a salary (including bonuses) of nearly $1 million in 2008, prompting Iowa’s Senator Charles Grassley to call for an investigation of how the organization used previous federal grants in preparation for Congressional consideration of a bill that would award the group a five-year grant of $425 million. At issue for Grassley and other legislators were top-heavy BGCA expenditures on executive salaries, travel ($4.6 million), and lobbying, , particularly because the BGCA ran a deficit of more than $13 million—and received $41 million in government grants—in 2008.

Oklahoma Senator Tom Coburn, a scourge of earmarks, noted that the Boys and Girls Clubs— the more than 4,000 local, independently run clubs—had received $550 million in federal support meant to expand clubs into underserved areas. But rather than expanding, the network was closing down club sites. Note that the BGCA contradicts Coburn and asserts that the number of local chapters of the organization has increased hugely, from 1,850 to over 4,300 since 1996 under Spillett’s leadership. None of the BGCA salary or earmarks controversy seems to have been a factor or even considered by the journalists involved with the James/ESPN show.

But what of James’ personal charitable endeavors? Like many megastar athletes, James has his own foundation engaged in charitable activities in the Akron area. Most of its activities have been bike-a-thons and other events where the foundation gives away the bicycles and helmets, though it also gives grants. The head of the Akron Boys and Girls Club effused about James’s importance to her organization, though our inspection of the superstar’s foundation’s 990s from 2004 to 2008 revealed only one Boys and Girls grant.

Giving the Boys and Girls Clubs $2.5 million dwarfs the foundation’s cumulative grantmaking, but remember, James didn’t give the Boys and Girls Club anything from the show. He (or his representatives) simply arranged for the T.V. show ad proceeds plus some additional corporate contributions to go to the charity. Even if you ignore his past salary of more than $14 million a year with the Cavaliers plus outside endorsement deals such as the 7-year $90 million agreement with Nike, James’s salary in Miami will be more than $100 million over six years—where in Florida, unlike Ohio, there is no state income tax. James could have probably very easily written a check to the Boys and Girls Club and sent a letter to the Cavaliers thanking them for a good first seven years in the NBA, but the show was more important to the self-proclaimed “King.”

This is the way the game is played, in high priced sports and in big-time charity. It’s a show, a fundraising event. Even if there was very little new information to be learned from the ESPN extravaganza about the Boys and Girls Clubs—good in their services to kids, mixed perhaps in their federal earmark performance, dubious in Spillett’s million dollar salary package—big money was at stake. Why would the Boys and Girls Club look a gift horse in the mouth? They wouldn’t and they didn’t.

Still, some of the show makes us queasy. We didn’t see James devoting any of his past and future fortune to the Boys and Girls Club, though hopefully he will. We’re all part of an entertainment-focused world. If you want to capture the charitable attention of the likes of LeBron James, more often than not it requires a show, an event, an extravaganza. It wasn’t just reality TV, it was reality big-time charity.