Editors’ note: The research for this article was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism. The article comes from NPQ’s summer 2015 edition, “Nimble Nonprofits: The Land of the Frugal Visionary.”

Imagine you’ve been invited to be a trustee of a longstanding family foundation. You join the board meeting and nod and exchange pleasantries with the other trustees—and then you are introduced to one whose affiliation might be Bank of America or JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Individuals and banks may be trustees (or cotrustees) of a foundation—that is, a trust established to charitably benefit a class of beneficiaries consistent with the instructions and priorities of the grantor of the trust, who can name as trustees individuals, banks, or both to carry out the beneficial purposes of the trust. As a trustee, you might not be able to shake hands with John Pierpont Morgan but you’ll know from the trust documents some of the powers of the bank trustee—typically, to be paid, often handsomely, for the foundation’s investment, management, and administrative functions. (Indeed, while more than likely your individual role as a foundation trustee is gratis, when a bank is serving as a trustee its interest may fundamentally be one of getting paid—and, in light of competitive pressures on banks’ bottom lines, getting paid profitably.)

Sometimes, however, bank trustees’ powers are more extensive—more like those of the trustee you might be—such as having a say in determinations about potential grant recipients’ qualifications for foundation dispositions, or suggesting modifications in the trust’s priorities if those priorities have become impractical or unnecessary.1 The bank trustee role is a business function built right into the operations of some foundations, but it gets scant attention among nonprofits. As a foundation trustee, however, you’11 be familiar with the latent power of the bank trustee—a power that Mary L. Smith, the widow of oilman William Wikoff Smith, discovered when the bank trustee of the W. W. Smith Charitable Trust attempted to get a large, retroactive fee increase for its role in administering the trust Smith left in support of medical research, college scholarships, food and clothing for children and the elderly, and maritime education.

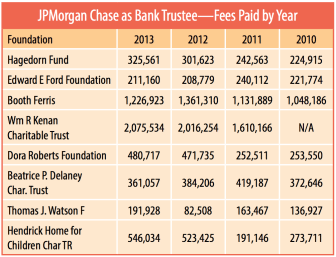

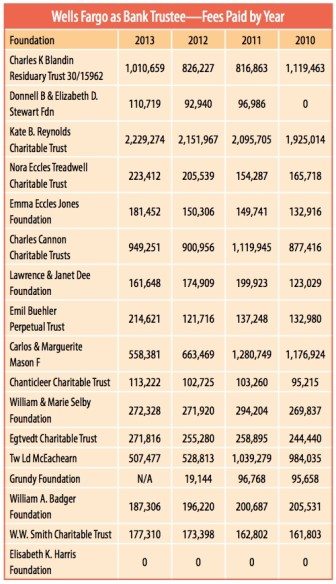

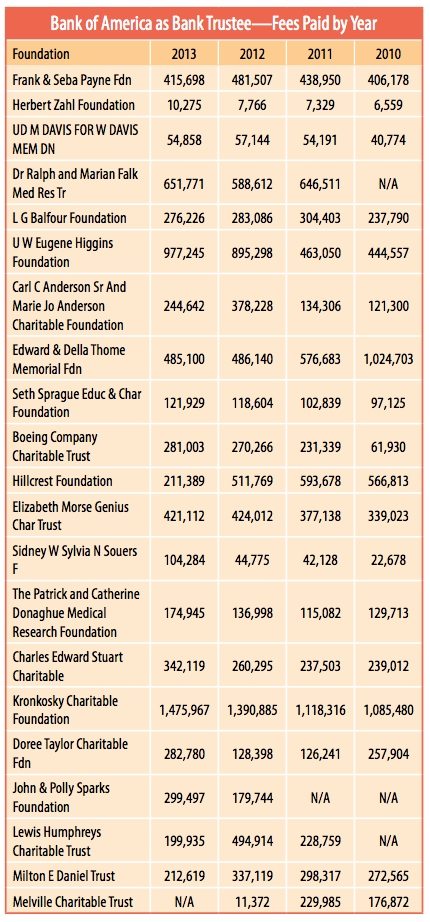

In this article, we look at the costs charged by a handful of large banks as trustees (not individual bankers as trustees) to private foundations that they serve—specifically, banks serving private foundations with assets of over $50 million. The costs are drawn from the 2014 financial information of three of the four largest banks in the United States: JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo (the fourth, Citigroup, does not appear to hold bank trustee roles with private foundations with over $50 million in assets). Given the mammoth size of these banks, the trustee fees earned from their services to foundations can hardly constitute a large slice of their profits. But banks are back to earning huge profits in our society, taking in just short of 30 percent of total U.S. profits, and higher profits than they were generating before the financial crisis of 2008.2 Increasingly, bank profits are dependent less on lending and more on other business activities. And while this analysis doesn’t establish exactly how profitable bank trustee roles with private foundations might be nor purports to calculate the bank trustee earnings of all banks, what it does establish is that three of the largest banks in the nation are functioning as bank trustees for dozens of foundations and earning substantial revenues for their services. For these banks—and likely for others—bank trustee roles constitute a revenue source that is largely unknown to the American public and even to most nonprofits.

Large Banks Earning Bank Trustee Fees

In the competition among American industries for the title of most distrusted, banks rank near the top. Sitting at the head of Time magazine’s list of the twenty-five people most “blameworthy” for the global financial crisis at the end of the last decade is Angelo Mozilo—once the CEO of Countrywide Financial Corporation, the nation’s largest mortgage lender, whose collapse led to a “rescue-sale” by Bank of America and a $8.7 billion settlement of predatory lending charges filed by eleven state attorneys general.3 In the view of the Economist, “Start with the folly of the financiers”—abetted by the ratings agencies such as Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s, entities that the public might have believed were trustworthy guides of investor risk but actually “were paid by, and so beholden to, the banks”— and end with a national and global collapse in the housing markets and overall financial systems of Europe and America.4 Although it is rising in public attitudes from the bedrock basement to which the industry sank, beginning in 2007 and 2008, the banking sector is still viewed by the American public, according to Gallup, as “below average”—a category that includes the airline industry, the pharmaceutical companies, advertising and PR firms, and electric and gas utilities.5

Not long before the national and global fiscal collapse, banks had earned themselves a troubled reputation in philanthropic circles, due to an unusual case in Philadelphia. Wachovia (now Wells Fargo) had been the bank trustee for the W. W. Smith Charitable Trust. Wachovia had inherited this fiduciary role when it acquired First Union Bank, which had been the bank trustee after it acquired CoreStates Bank, which itself had become the Smith trust’s bank trustee when it absorbed Philadelphia National Bank (PNB)—and so on during the wave of serial bank mergers and acquisitions that occurred in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s.6 And that trustee wanted an increase in its annual fee—a shift in the calculation to a percentage of the trust’s total assets rather than a percentage of its annual income; in 1998, when First Union made the request, this would have more than tripled its annual fee, from $261,799 to $914,370. First Union and then Wachovia as its successor also asked that the fee be increased retroactively for the previous fifteen years, on the theory that the bank trustee had been inappropriately undercompensated ail that time. The trust’s only other trustee, Smith’s widow, didn’t agree, and the bank trustee went to court and challenged the institution it purportedly served as a fiduciary.

“Why Mr. Smith put that provision in his trust is he wanted this money to go to charity, not to PNB, and he wanted a reasonable limitation on it,” Lawrence Barth, a senior deputy attorney general, said about the controversy. “And experience has shown, in this case, that the bank can live within it, and should live within it, and should not gain windfalls.”7 The notion of 5 percent of assets, as First Union and then Wachovia requested as a fee, was essentially equivalent to what nonprofits would expect as the mandatory minimum qualified distributions, or “payout,” from a private foundation (or, if increased, a potential “windfall”)—not a service fee to a bank. Charity might have had more at stake in the outcome of the litigation than just the Smith trust assets if Wachovia could sue to get higher fees going back years. For most of the nonprofit world, the idea that a big bank might earn a million dollars a year for serving as a trustee to a foundation with a somewhat limited range of activities was unknown. “If Wachovia wins this case, they’re coming after other private foundations and other high-net-worth individuals with trusts who give away lots of charitable donations,” Bruce W. Brown, a former administrator of the Smith trust and senior official at two other Philadelphia foundations, told the Chronicle of Philanthropy. “Charities need to pay attention to this, because they’re the ones who could lose.”8

A 2003 Georgetown Public Policy Institute study examining 238 foundations found in their 1998 Form 990 filings that twenty-five of them had paid their bank trustees in the aggregate of $13,837,726, and observed, “The 990-PF’s provided no details about the bank trustees. It was impossible, therefore, to assess the services that banks provided to the foundations and the banks’ relationships to the principals at the foundations.”9

The analysis collected information about any bank that might have served as a bank trustee for the foundations in the sample of that study. Although the number of federally insured financial institutions has fallen to its lowest level since the federal government began counting banks in 1934, there were nonetheless 6,891 commercial banks in existence as of September 2013—an untold proportion of which may be serving charities and foundations as trustees.10

The following table shows the twelve largest banks in the nation according to SNL Financial:11

The table reveals at a glance the extreme concentration of assets and deposits in the top four banks. For example, the total assets of the fiftieth-largest bank in the United States, FirstMerit Corp., based in Akron, Ohio, are less than one 1 percent as large as JPMorgan Chase’s.

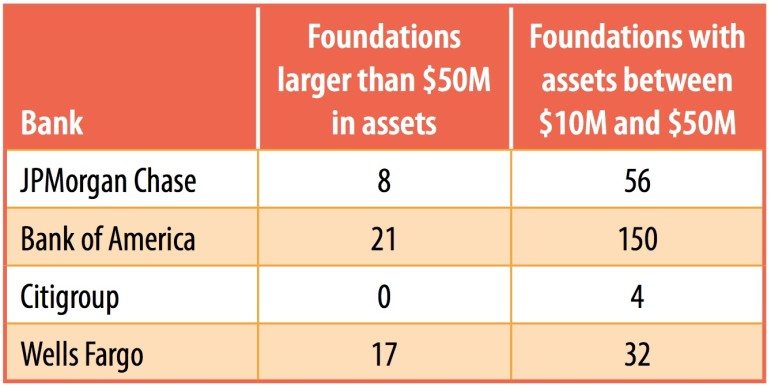

After reviewing multiple potential sources of information, the Nonprofit Quarterly chose to rely on GuideStar to identify private foundations for which JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo served as paid bank trustees to 501(c)(3) nonoperating foundations with assets over $50 million (excluding the banks’ own corporate foundations).12 Based on the GuideStar advanced search mechanism, the total number of foundations worth above $50 million with these banks in official trustee roles breaks out as follows:

Adding in foundations with between $10 million and $50 million in assets, Citigroup shows up as a bank trustee serving a small number of private nonoperating foundations. Overall, the distribution of private nonoperating foundations with bank trustees from these four megabanks is as follows:

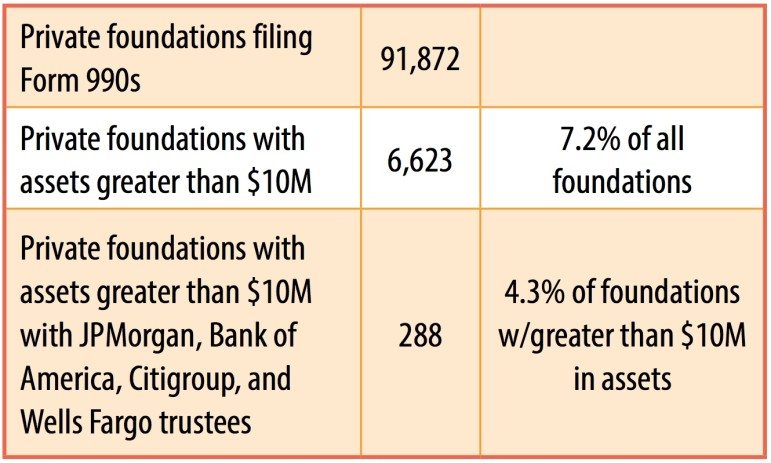

A total of 288 private nonoperating foundations have bank trustees from these four banks. It may seem like a small number, except that only 6,623 private foundations in the entire nation have more than $10 million in assets:

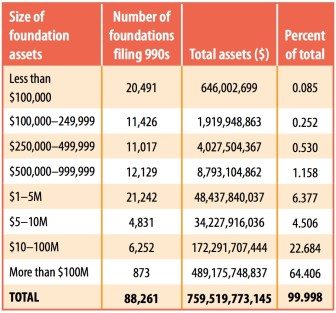

Although a relatively small number of foundations have assets above $10 million, those few control a large part of private foundation assets:13

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As the table demonstrates, more than 87 percent of foundation assets reside in foundations with $10 million or more in assets. Beyond the four largest banks, others among the larger banks also serve as bank trustees, sometimes for well-known foundations:

- Bank of New York Mellon is a bank trustee for the Arthur Vining Davis Foundation, known to many for its support of public television and longstanding partnership with filmmaker Ken Bums;

- PNC Financial Services is the bank trustee for more than seventy private foundations with assets of greater than $10 million, including the Pittsburgh-based McCune Foundation and the Ruth Lilly Foundation. Another PNC foundation is the GAR Foundation, which contributes significantly to the Fund for Our Economic Future, in Cleveland, Ohio;

- Capital One is a bank trustee for the C. Homer and Edith Fuller Chambers Foundation, in New Orleans, and several other foundations in Louisiana; and

- Regions Bank is the bank trustee for the Robert R. Meyer Foundation of Birmingham, Alabama, whose grant application strongly encourages applicants to join the Alabama Association of Nonprofits.

The foundations that have as bank trustees JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, or Wells Fargo are no less well known. JPMorgan Chase’s Booth Ferris Foundation is particularly well known in the New York City area for its support of human service agencies such as the Henry Street Settlement and the now-bankrupt Federation Employment & Guidance Service (FEGS).14 In 2014, the William G. and Marie Selby Foundation, with Wells Fargo as its bank trustee, gave $200,000 to the Conservation Foundation of the Gulf Coast for the purchase and dedication of a conservation easement on the Myakka River in Florida.15

As noted earlier, the role of a bank trustee is much broader than simply functioning as a vendor to a foundation for a series of discrete managerial and investment tasks. The role includes investing foundation assets, balancing spending and investment priorities, and pursuing and protecting donors’ interests and priorities. While meant to protect the charitable and philanthropic interests of donors, bank trustees can also exercise significant control over the assets of foundations. For example, a bank trustee might resist supporting movements to increase the social or mission investment of assets and instead emphasize investments for return. While a bank trustee might be able to resist conflicts of interest that individual foundation trustees could in theory succumb to—that is, individual enrichment and personal inurement—bank trustees have been challenged for selling the banks’ own products to the foundations they serve or investing foundation assets in bank equities. And, when the relationship of the founders and donors to their foundations becomes more attenuated (as at times it does), the potential latitude of the banks to exercise power grows.

Most of the foundations’ 990s examined here indicate that the banks spend approximately thirty-eight to forty hours a week in their bank trustee roles. One of the least reliable data points in a 990, however, is the estimate of hours worked by trustees—individual or corporate. Whether or not the bank trustees are devoting that much time to their roles at the foundations in question, we suspect that the bank trustee function is not a charitable contribution on the part of the banks. Back in 2000, a presentation by Standish Smith of HEIRS® outlined an issue that warranted monitoring—the profitability of the bank trustee role. Smith suggested that some corporate trustees might occasionally be “tempted to blur the line between the right to control (the legal interest) and the right to enjoy (the so-called beneficial interest)” of the foundations and trusts they are charged with overseeing.16 Specifically, he identified several factors that could make the banks’ roles as trustees a little less than trustworthy at times—notably, the profitability of the function (particularly the profitability of the banks’ trust and investment departments), citing operating margins of between 30 and 45 percent. Given returns that high, bank trust departments could in many cases cut the fees they charge for their trustee functions and thereby increase the amount of money available for the trusts’ or foundations’ charitable distributions; however, with increasing competitive pressures in a consolidating market, banks might start looking at their trustee function as an arena for upping the revenue they make from private foundations as well as for building power via their control over these foundations.

Charitably Trusting the Banks

For the sake of argument, we can assume that in most cases bank trustees try to treat the foundations they serve fairly and then some. As small parts of the business economics of large banks, bank trustee functions shouldn’t be all that attractive an arena for profit-motivated banks to maximize their returns. However, as suggested above, this changes after a merger or acquisition, and is exacerbated by the competitive pressures the banks face following the Great Recession.

A major motivation in bank mergers is to achieve efficiency through stripping the two or more united entities of redundancies, reducing unnecessary costs, and maximizing potential returns wherever they exist in the combined megabank. That includes raising what the new megabank owners might see as inadequate compensation to make the role of bank trustee more productive vis-à-vis financial return to the bank. That First Union and then Wachovia would want to triple their fee as a trustee and hike fifteen years of back fees as well is, in the business models of bank mergers, understandable. Of course, a push from banks for higher trustee fees is likely to be met in some cases—when the foundations’ founders or other trustees are paying attention—with pushback by nonprofits trying to maximize philanthropic resources and minimize nonphilanthropic administrative fees.

JPMorgan Chase is the product of mergers and acquisitions, including Manufacturers Hanover Corporation, Chemical Banking Corporation, First Chicago Corporation, The National Bank of Detroit (NBD), Bank One Corporation, The Chase Manhattan Corporation, and Washington Mutual Bank. Bank of America, as it stands today, is the product of a merger with NationsBank, several additional acquisitions such as FleetBoston, and, in the wake of the financial crisis, Countrywide. Wells Fargo today reflects other banking giants that were acquired by Wells or by the banks Wells acquired, such as First Fidelity Bancorp, First Union, CoreStates, Wachovia, and the troubled World Savings Bank. As the relationship between the original bank trustee and the philanthropic donor becomes attenuated by the passage of time—and, in U.S. banking, often serial bank mergers and acquisitions (which more often than not result in formerly local bank trustees moving out of state)—it should not be surprising that what was once a bank service to longstanding wealthy depositors develops into more of a business relationship between the bank trustees and the foundations they help govern. That makes the W. W. Smith case an example of a struggle over fees and services that could become more rather than less likely, as banks feel the pressures to make every possible cost center one that comes out well in the black.

At roughly the same time as the W. W. Smith Charitable Trust case came before the courts in Philadelphia, a flurry of attention was focused on other cases—these questioning the fees charged and/or the services that banks delivered for those fees in their roles as bank trustees. In a 2005 article published in the Chronicle of Philanthropy, Brad Wolverton indicated that some banks were reducing the trustee services they provided under their current fees or, like Wachovia, were suing for fee increases. As summarized in the Chronicle, “Many charities and foundations believe they are losing millions of dollars a year to the very institutions they pay to safeguard their assets.”17 Richard D. Greenfield, a lawyer from Easton, Maryland, representing, according to the Chronicle, various trusts and foundations challenging the banks, put it like this: “Bank officials don’t think anyone is going to raise a big fuss if excessive fees are taken, and they have learned from experience that members of foundation and charity boards tend not to rock the boat.”18

Why would a donor choose a bank as opposed to an individual to serve as the trustee of a charitable entity?Wealthy individuals or families thinking about establishing a charitable trust—that is, a philanthropic grantmaking entity—sometimes choose corporate trustees, such as the trust department of a bank, to manage their assets and ensure that the charitable purpose of the trust is maintained. Often, the choice of trustee is a bank with which the donor has a long-established relationship. Among the multiple reasons a donor would choose a bank might be: the bank’s experience in the management of trusts and estates; the bank’s experience in investment of assets for maximum returns; the reliability of an “institutional” trustee as opposed to an individual trustee (who might have personal concerns and agendas); the bank’s presumed fidelity to the donor’s charitable priorities and intent; the bank’s hoped-for neutrality and objectivity in the face of the competing interests of a donor’s various family members; and, in theory, the bank trustee’s institutional continuity as compared to individual trustees who might leave the foundation board for one reason or another. As more individuals and families generate significant asset holdings that they want to insulate from estate taxes, wealth advisors increasingly suggest that potential donors establish irrevocable charitable trusts and select corporate trustees—that is, the trust departments of banks as well as other trust administrators—to ensure their assets get used for the charitable purposes the donors want and expect while alive and after they are gone. |

As noted earlier, making a bank a trustee for a foundation, particularly with few other trustees to counter it, gives the bank broader powers than some observers might assume. Wolverton writes about the McCune Foundation of Pittsburgh suing its then-trustee National City Bank in Cleveland, not only for improperly overseeing the investment of foundation assets but also for refusing to allow family members a voice in the investment decisions, and for investing much of the foundation assets in the bank’s own stock. McCune lost in court (although, according to Wolverton, the foundation continued to criticize the bank publicly). As James Edwards, a member of the McCune board, told the Chronicle, bank trustees “want to act like they don’t have a conflict of interest, but any fool can see they do.” A similar challenge to Bank of America (having acquired Pacific National Bank and others) succeeded, finally, in making the case that it had overbilled trusts and foundations for some years, with a U.S. Court of Appeals judge ordering Bank of America to pay $111.5 million in punitive damages and restitution to thousands of claimants.

In 2005, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled unanimously in favor of Mary Smith and against Wachovia’s request to receive a retroactive hike in its fees.19 The decision overturned a lower court decision that had gone in Wachovia’s favor, with the implication that Wachovia might have to return to the Smith trust the higher fees it had begun awarding itself at that time.20

According to the Smith trust’s former administrator Bruce Brown, William Smith had a personal relationship with G. Morris Dorrance, the former chairman of PNB, who served as the institutional cotrustee of Smith’s foundation. But with First Union and then Wachovia, the Smith trust had a bank trustee that was no longer local but based in Charlotte, North Carolina; and, as Brown noted, “Dorrance knew Bill Smith—his interests, his passions, his intentions for his charitable funds. Not one of the ‘revolving door’ representatives from North Carolina-based Wachovia knew Bill Smith.” It was a relationship of trust—the root of the concept of trustee; “no such relationship of trust exist[ed]…between Mrs. Smith and Wachovia, a banking institution foreign to the Philadelphia market.” Wachovia, in Brown’s opinion, could “take advantage of’ the law and “fatten its bottom line, but any increased fees will come out of the pockets of charitable grant recipients.” The Smith case and other cases of charities struggling with their bank trustees reflect a different/past economy—one in which the local banker in the trust department knew well the wealthy clients it served as institutional trustee for their charitable foundations.

Brown suggests that the Smith case showed that the concept of a bank’s “trust department…[now is] an oxymoron.” For as charities have discovered in dealing with bank foundations, increasingly the program officers aren’t within their communities but rather hundreds or even thousands of miles away. In 2007, a report by the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy described the postmerger situation succinctly:

Community advocates… may fear a shift in decision-making power out of the acquired company’s community, resulting in a loss of affinity or loyalty—a fear that there will be no one at high levels of leadership in the new mega-corporation who cares about the concerns of their community; neither face-to-face conversations nor creative thinking will take place to address local needs. Another concern includes whether a larger mega-corporation will shift focus away from a unique set of local needs to a national set of priorities. Lastly, there is the fear that funding will be stripped from local organizations to give to larger, regional, or national organizations that can provide wider publicity for the post-merger bank, thus better enhancing the bank’s public image while providing a significant administrative ease of fewer grantees within a larger budget.21

With the bank trustees serving charitable foundations, the dynamic is much the same. The relationship is likely to be impersonal, institutional, and distant. The banks’ view of the bank trustee role may in some circumstances be less about service and more about business. In much of the litigation that has emerged around bank trustee roles, donors and foundations have complained that the banks are putting their own priorities, including sometimes the banks’ own philanthropic objectives, over the philanthropic priorities of the founders, donors, and family members involved in the charitable institutions.

When the bank trust department fulfills its bank trustee role with a charitable trust or private foundation, the calculus may well emphasize the bank’s economic return as much as the foundation’s charitable distributions. In the Form 990, aspects of what the bank trustee might be engaged in doing—the management of assets, investments, and capital flows—may be the least understandable, least consistent, and most opaque information presented in the IRS filings. Although speaking about the trustee reports in general—but applicable to the information in Form 990s—Standish Smith noted the problem of understanding and interpreting the banks’ reports, not only by external watchdogs but also by foundation insiders themselves: “The trust accounting statements to which I have been exposed do not always appear to be models of clarity or disclosure. That’s unfortunate, since the trustee-beneficiary relationship is, in theory, a fiducial relationship of great sensitivity, it seems beneficiaries should be entitled to statements that are timely, comprehensive, detailed and understandable.”22 Presumably, most bank trustees balance the banks’ own financial imperatives with the interests of their foundation or charitable trust clients. For those that don’t, the importance of watchdogs that monitor—and understand—Form 990 filings to track how much banks earn from their bank trustee roles and how they are investing the foundations’ moneys cannot be overstated: as Smith observed, every dollar that is paid to Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, or Wells Fargo in excess of what the banks need and deserve is a dollar that could have gone to a charity instead.

W. W. Smith Postscript

After years of litigation, what happened to the fees that the W. W. Smith Charitable Trust was ordered to pay its Wachovia (subsequently Wells Fargo) bank trustee? While the fees skyrocketed in fiscal year 2003 as Wachovia took advantage of the lower court ruling that increased its compensation, the fees subsequently fell in later years in response to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruling, as the graphic below makes clear.

The ratio of the bank trustee fee to the foundation’s assets in 2013 is roughly back to where it was in 1999, except for the years that the Smith trust shelled out substantial legal fees, including $472,665 in 2002 and $77,379 in 2005. Basically, the bank trustee and the foundation have come full circle, minus the costs incurred in the litigation—and the mental toll it took on Mary Smith—when the friendly trust from the local Philadelphia bank that had handled the Smith family’s philanthropic interests for so many years transformed into a distant trustee, located in North Carolina and then beyond, that viewed the foundation as a revenue source rather than an entity to safeguard and protect.

Notes:

- See, for instance, Quarrie et al. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 603 F.2d 1274 (1979), addressing the powers of the Northern Trust Company, the bank trustee of the William F., Mabel E., and Margaret K. Quarrie Charitable Fund: “In the event that at some future date, any of the aforesaid charitable uses in the judgment of the Northern Trust Company shall have become unnecessary, undesirable, impracticable, impossible or no longer adapted to the needs of the public, the income otherwise to be devoted to such use shall be distributed to such charitable, scientific, educational or religious corporations, trusts, funds or foundations as the Northern Trust Company may select to be used for their general purposes.”

- Ben Walsh, “No, Regulation Is Not Keeping Banks From Making Money,” Huffington Post, November 12, 2014.

- “25 People to Blame for the Financial Crisis: Angelo Mozilo,” Time, accessed May 4, 2015.

- “The origins of the financial crisis: Crash course,” Economist, September 7, 2013.

- Frank Newport, “Business and Industry Sector Images Continue to Improve: Images of 24 business sectors are most positive since 2003,” Gallup, September 3, 2014.

- Patricia Horn, “Legal fight could hurt trust’s giving: Wachovia wants a bigger fee, plus $5 million for work from the past,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 25, 2004.

- Ibid.

- Brad Wolverton, “Bank Sues Philadelphia Trust in Quest for Additional Compensation,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, April 14, 2005.

- Christine Ahn, Pablo Eisenberg, and Channapha Khamvongsa, Foundation Trustee Fees: Use and Abuse (Washington, D.C.: The Center for Public and Nonprofit Leadership, Georgetown Public Policy Institute, September 2003).

- Constantine Von Hoffman, “Number of U.S. banks drops to record low,” Moneywatch, CBS News, December 4, 2013.

- Zuhaib Gull, “Top 50 US banks in Q4’13,” SNL Data Dispatch, February 27, 2014.

- This review also excludes entities identified as 4947(a)(1) Non-Exempt Charitable Trusts. As defined by the IRS, “In general, a private operating foundation is a private foundation that devotes most of its resources to the active conduct of its exempt activities. [It] may qualify for treatment as a private operating foundation. These foundations generally are still subject to the tax on net investment income and to the other requirements and restrictions that generally apply to private foundation activity. However, operating foundations are not subject to the excise tax on failure to distribute income.” In other words, unlike nonoperating foundations—which are foundations that do not “operate” programs—operating foundations don’t have a payout requirement.

- National Center for Charitable Statistics, Urban Institute.

- “2014 Contributions—Strengthening NYC,” Booth Ferris Foundation.

- “Summary of Foundation Grants,” William G. and Marie Selby Foundation.

- Standish H. Smith, “Reinventing The Corporate Administration of Personal Trusts—A Marketing Opportunity For Banks” (presentation to the Financial Analysts of Philadelphia, The Racquet Club of Philadelphia; April 20, 2000).

- Brad Wolverton, “Loss of Trust,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, April 14, 2005.

- Ibid.

- Patricia Horn, “Court blocks unilateral hike in trustee’s fees: Wachovia Corp. barred from raising trust fees,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 29, 2005.

- W. W. Smith Charitable Trust v. Wachovia Corporation, J. E04001/04 (Pa.Super. 2005).

- Becky Sherblom, Banking on Philanthropy. Impact of Bank Mergers on Charitable Giving, (Washington, D.C.: National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, June 2007).

- Smith, “Reinventing The Corporate Administration of Personal Trusts.”

Rick Cohen is the Nonprofit Quarterly’s national correspondent.