“FREE FALL FISH” BY GAIL TROTH / WWW.GAILTROTH.CO.UK

Editors’ note: This is the first of two parts of this article, the second of which will appear in NPQ’s fall 2013 edition. The article started as a paper titled “Promoting Passion, Purpose, and Progress Online.” It was first published online by Alliance Magazine, in February 2013. This article is featured in NPQ‘s blockbuster summer 2013 edition: “New Gatekeepers of Philanthropy.”

Over the past fifteen years, scores of American social entrepreneurs have tried but been largely frustrated in their efforts to promote more intelligent, proactive, and generous phi- lanthropy via the Internet. For the most part, they have been unable to bring their databases, persistent. Like the online philanthropy entrepreneurs, nonprofit leaders are frustrated by their own failure to exploit the transformative promise of the Internet. The early Internet experience has been equally frustrating for managers of nonprofits. They are buffeted by numerous increasingly intense and generally conflicting demands for information. They receive inconsistent market signals from donors, both individuals and institutions, and watch the great bulk of online giving flow to causes that are hot, visual, and immediate instead of to those that are thoughtful, well managed, and persistent. Like the online philanthropy entrepre- neurs, nonprofit leaders are frustrated by their own failure to exploit the transformative promise of the Internet.

While frustrating, this result was predictable. Our efforts to promote online philanthropy are stuck in a tangled web of ineffective and incon- sistent practice that extends throughout the universe of philanthropy. We have sought, through our sophisticated tools and exhaustive data, to untangle a part of that web. Certainly there have been bright spots—modest untangling and change has occurred here and there. But the pace of that change has been painfully slow. This paper argues that change will continue to be hampered unless we invoke strategies to untangle the entire web—that is, remove impediments that inhibit progress throughout the entire philanthropy ecosystem, which is the aspirational name I use in this paper to describe the interconnected, information-driven, innovation-embracing philanthropic universe we must resolve to build together.

This paper revisits early initiatives to facilitate more generous and intelligent philanthropy, and flags the causes of entrepreneurial frustration. It then discusses, in turn, the pertinent attributes and challenges facing each of four component systems of an inclusive philanthropy ecosystem: the philanthropy knowledge system; the giving system; the nonprofit management and reporting system; and the nonprofit evaluation system.1 It concludes the discussion of each component system by identifying opportunities for social entrepreneurs to intervene productively. And, it highlights the systemic potentials of the philanthropic universe and the necessity for social entrepreneurs to pursue opportunities for coordinated or collective action across the ecosystem. Indeed, without a commitment to build this ecosystem together, the entrepreneurs and others who build and lead nonprofit organizations will continue to operate within a confusing and ineffective resource marketplace. And, most importantly, the people and planet served by these actors will be denied the benefits of a well-functioning philanthropy ecosystem.

The Drive to Make Giving Better: Early initiatives Revisited

We haven’t always sought to turn donors on to the rewards of smart, proactive philanthropy. We haven’t always believed that we could elevate them to greater heights of discerning generosity by offering them immediate access to evaluative, fiscal, and programmatic information about nonprofits. Indeed, throughout its long history, American philanthropy has been very slow to move from its longstanding association with alma maters, churches, hospitals, and other local institutions—an association fortified by friends, family, pride, and proximity—to embrace the hundreds of thousands of distant, more cause-focused nonprofits that proliferate around the planet.

Community Chests and United Ways

Attracting the attention and allegiance of new donors has always been a difficult and expensive proposition for nonprofits that lack human ties to their targets. The most successful have deployed sophisticated marketing methods of messaging, direct mail, and friends-of-friends networking. Throughout the twentieth century, local Community Chests and their United Way off-spring popped up to capture and rationalize donor interest in local social agencies. While still relying on tried-and-true direct mail and a network of workplace “arm twisting,” United Ways have long researched local community need and purported to fund the most effective charitable responses. In this way they conduct, albeit not always cost-effectively, the evaluation and funds-sourcing functions for local charities that online intermediaries, as we will see, seek to do for nonprofits and causes throughout the world. But note that, despite their ubiquity and longevity, United Ways still process less than 2 percent of total giving.

The National Charities Information Bureau, Better Business Bureau, and American Institute of Philanthropy

Direct mail campaigns by national nonprofits seeking donations countrywide grew in prominence in the 1960s and 1970s. In response, state charity offices and national watchdog groups, principally the National Charities Information Bureau (NCIB), Better Business Bureau (BBB), and American Institute of Philanthropy (AIP), emerged to protect the public from fraudulent solicitors and inefficient charities. NCIB and BBB, each working with populations of roughly 350 nonprofits, identified those organizations that exceeded their standards and those that fell short. AIP offered letter grades for selected standards for the six hundred nonprofits it rated. The expressed purpose of these efforts was consumer protection, and the primary focus of analytical attention was nonprofit fundraising practice. The perverse upshot of the whole exercise has been a widely accepted, two-generations-long tradition of nonprofit evaluation based largely on the magnitude of fundraising and administration ratios.

The NCIB and BBB combined operations in 2003, revisited respective evaluative standards, and now offer a more holistic view of general fiduciary practice, as well as fundraising practice, in their reviews of 1,200 nonprofits.

GuideStar and Charity Navigator

GuideStar launched its comprehensive website in 1998, offering extensive financial and limited descriptive information, all self-reported and non-evaluative, on the hundreds of thousands of nonprofits that complete the Form 990. GuideStar assembles vast amounts of data from all American nonprofits, which helps donors and others to identify, compare, track, and connect with groups performing work that resonates with their own interests and values.

Charity Navigator, also seeking to take advantage of the data management and broad distributional functionality of the web, was founded in 2001 and has become the most highly trafficked website of the evaluative services. Using a relatively few financial data fields from the Forms 990 of 5,500 organizations, it applies star ratings for each of four indicators of the financial efficiency of organizations and three indicators of the financial capacity of organizations. Charity Navigator has sought lately to reorient its evaluative model to focus increasingly on organizational accountability and results, thereby diminishing its single-minded focus on simple financial calculations, an evaluative method now largely in disrepute.

The formation of Network for Good, originally a partnership of AOL, Yahoo!, Cisco Systems, GuideStar, and VolunteerMatch in 2000, provided a pivotal and instructive moment in this concentrated historical development. The question arose whether GuideStar should use its mountains of data to construct and display an evaluative framework, like the one eventually launched by Charity Navigator, but on a much larger scale. The principals at the time determined that GuideStar must remain a neutral aggregator of this largely self-reported information by charities. Beyond continuing to digitize the voluminous financial data resident in the Forms 990, they determined that GuideStar should strive to capture additional narative information about the intentions, program activities, objectives, and accomplishments of all charities.

GuideStar’s principals subscribed to the theory that a nonprofit’s “worthiness” was largely a function of the values of the evaluator or other observer. Further, if it could assemble all the pertinent information about each organization and provide the robust mining and analytical tools, donors could theoretically do their own ranking and rating. GuideStar had confidence in the integrity of the do-it-yourself theory, but acknowledged that a donor public would likely seek the help of “expert” evaluators to help them identify the right organizations. It envisioned the ultimate emergence of a substantial network of evaluators, each bringing differing institutional perspectives, fundamental values, and subject and geographic expertise to proprietary evaluative models. It used the “movie critic” metaphor to explain its vision that one day millions of disparate donors would come to trust the judgment of one or more scores of evaluators to identify worthy nonprofits. In this conception, GuideStar would play a valuable role in supporting the emergence of this network of evaluators with data and Internet visibility.

Happily, new evaluation schemes seem to emerge regularly, and other new efforts that identify “excellent” giving opportunities (e.g., GlobalGiving) evaluate implicitly through their choices of programs to display, though they do not rank or rate nonprofits. Just as we have seen in every other walk of life, philanthropy has seen an explosion in information sites, Web 2.0 interaction sites, and now directly focused social network initiatives, such as scores of apps and thousands of custom pages grafting philanthropic services and nonprofit causes onto the Facebook platform. With these developments, perhaps we will go full circle, once more depending upon friends and virtual neighbors for the connections to social expression through philanthropy.

Progress to Date

So far, despite the churn, time has told a disappointing story. The amount and quality of philanthropic activity springing or gaining confidence from serious evaluative activity, at least that which can be adduced from web activity, is hardly in line with the expectations of the early Internet social entrepreneurs. In 1999, Pete Mountanos promised that Charitableway would become the “Amazon of philanthropy.”2 It was a little scary, but we believed him. While the hubris of subsequent initiatives has not matched that of this pioneer, our own founding expectations have rarely been fulfilled. Certainly the full value of online information services in supporting offline donations has not been studied adequately, but the contention that the web has revolutionized donor behavior, as it has virtually every other human transaction, is not remotely supported by the data.

The early frustrations have not inhibited efforts to use electronic technology and the web to rationalize and facilitate giving. But, like the wild philanthropic marketplace they seek to tame, these efforts are all over the map with respect to motive, method, and message. This uncoordinated entrepreneurial quality is at once the strength and continuing weakness of this movement. Operating independently, without a holistic view of the ecosystem they hope to improve, online initiatives today constitute little-heard noise in a vast forest of nonprofits.

By no means does our sketchy early experience demand that we cease these efforts, but this will remain a tough road. In the larger economy, Internet information and transactional services succeed when they offer “consumers” a value proposition that builds upon current, self-interested decision processes. Like Amazon or E*Trade, our online philanthropy solutions also ask users to change to electronic transaction processes. But the success of these ventures also requires our users to switch from an affiliative, borderline-self-interested decision process to one that is more discerning, “other” centered, and cause related.

The institutional barriers to the success of online ventures do not end there. Lest we forget, another major operating challenge these initiatives face is the need to capture information about large numbers of nonprofits to feed proprietary databases. This requirement compels each service to ask nonprofit organizations to report differently and, at times, behave perversely, in reaction to our requests for information that are varied, conflicting, and often internally irrelevant.

The online philanthropy entrepreneurs could take comfort in the knowledge that they are not alone. Numerous systemic barriers to so-called rational behavior limit the progress of innovative initiatives in other areas of the philanthropy ecosystem, such as the promotion of “impact reporting,” the sharing of grantee due diligence data, and the encouragement of best grantmaking practice by foundations. However, the continued failures of these initiatives bode poorly for our own. In practice, we need these types of initiatives, which lift the entire ecosystem, to succeed.

An Alternative Vision for the Philanthropy ecosystem

We have not succeeded to date because we have not accounted for the complexities and contrary economies of philanthropy as it exists today. We are attempting to interject creative online methods into a philanthropy ecosystem that does not yet value, promote, and reinforce the importance of information, consistency, or effectiveness. If we continue to innovate without a sense of the whole and without assiduous attention to the major driving conditions, we will continue to spin our wheels.

But if we can step back and examine the methods, signals, and accountability of the entire philanthropy ecosystem, we will not only improve the prospects for the existing online intermediaries but also identify multiple additional opportunities for fruitful intervention. We will recognize that, far from a zero-sum shootout among the current group of online entrepreneurs, if we are to elevate philanthropy and nonprofit practice appreciably, many more savvy intermediary actors will likely be needed to innovate in what may yet become a vibrant, continuously improving philanthropy ecosystem. But first, we should attempt to reach agreement on a vision for an ecosystem that we intend to help build together. Here is my candidate for that vision:

The nonprofit sector will play an increasingly and recognizably effective role in our social economy and civil society. Its initiatives will continue to capture and offer institutional expression to the hopes, ideas, and energies of private citizens. But in the near future, supported by strategically coordinated information and transactional (mostly online) services, it will do so in ways that are at once more purposeful, coordinated, and accountable. Individual donors will seek out and support organizations that are doing work that they value.

Institutional donors will be accountable, consistent, transparent, intentional, and demanding in their philanthropy. Communities will articulate common objectives and track collective progress. Nonprofits will report consistently about their own objectives and institutional progress. Resources will be directed to organizations that best meet society’s evolving needs. Superior social and environmental progress will result and our liberal democracy will be strengthened.

Properly construed, these activities operate with a set of semi-discrete component systems that in turn are nested within an encompassing philanthropy ecosystem. Innovative but mutually reinforcing work by numerous intermediaries, existing and prospective, within and across the systems, will be needed if we expect to strengthen the entire ecosystem and advance social and environmental progress as a result.

To explain the workings, impediments, and opportunities of the philanthropy ecosystem more fully, I have divided its principal activities into the following four component systems, which are ostensibly discrete but ultimately interconnected:

1. The philanthropy knowledge system. The theoretical repository of pertinent social and environmental indicator data; government and corporate activities and policies; community objectives; and expert opinion about effective intervention methodologies that informs, constrains, and motivates nonprofits, donors, and intermediaries in the philanthropy ecosystem.

2. The giving system. The complex network of donors, trustees, institutional advisors, online transaction services, and formal philanthropic institutions that originate and/or manage over $300 billion in annual charitable gifts and grants.

3. The nonprofit management and reporting system. The process of objective setting, planning, performance tracking, and reporting that resides at the heart of every excellent nonprofit organization’s management system.

4. The nonprofit evaluation system. The network of auditors, evaluators, accreditors, regulators, experts, information websites, journalists, friends, and others who seek to inform, influence, validate, and/or protect donors and their decisions.

In the sections that follow, I have attempted to depict each system’s salient attributes, its interconnectedness with other systems, the bottlenecks and inefficiencies that impede its success, and the opportunities for tech-savvy social entrepreneurs to intervene and innovate.3

The Philanthropy Knowledge system

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Donors, nonprofits, and intermediaries respond to what they hear and learn from the news, public opinion, policies of governments and corporations, studies of successful interventions, and explicit community objectives. The torrent of information that drives disparate behaviors of the actors in the philanthropy ecosystem is chaotic, and the signals these actors send and receive are inconsistent. If we expect to achieve our vision for a more intentional and connected philanthropy ecosystem, we must find better ways to access and assess this information and convert it into actionable knowledge. The following categories of information are particularly important and promising, and will comprise a robust philanhropy knowledge system to support the philanthropy ecosystem.

As we convert chaotic information into useful knowledge, it is critical to establish a common language and frame of reference. Today, we can access compelling data indicating the status of virtually every issue, which can support interventions at every level. The State of the USA, a nonprofit based in Washington that seeks to provide exhaustive indicator data with a toolbox of visualization tools, is one of dozens of compelling new services.

With excellent indicator data readily available, we should expect political leaders, communities, and private citizens to identify priority indicators to establish and track consistent objectives for progress for each priority indicator. If donors and nonprofits synchronize their objectives with those of their communities, we can expect information chaos to dissipate and collective action to emerge.

The marketplace of expert opinion is vast and uncoordinated. Foundations commission and fail to share proprietary studies about needs, data, and effective interventions. Nonprofits are asked sporadically to assess the impact of their own programs. Little is done with this information. There is a great need for a public repository of expert opinion about effective solutions and useful interventions.

Very often we think of the nonprofit sector as a closed system in which much of society’s good work is performed. We acknowledge that government also performs much good work, though that assessment is continuously challenged. We seldom think about the role of business, beyond corporate social responsibility, with respect to its positive impact upon social or environmental objectives.

We have an excess of information swimming around, or more likely lying dormant, in the filing cabinets of foundations, government entities, nonprofits, and academics. Making the best of this information accessible and useful, turning it into knowledge that can power collective action and consistent provision of resources to effective nonprofit programs, is both a critical need and a tremendous opportunity for the Internet entrepreneur who wants to change the rules of the game. Without this common and virtual repository of knowledge, we cannot materially improve the effectiveness of the nonprofit sector.

What Is the Importance of the Knowledge System within the Philanthropy Ecosystem?

The knowledge system provides the context for the strategies and actions of each of the ecosystem’s participants and predicates defensible so-called theories of change. A properly functioning knowledge system will offer greater clarity about the absolute and relative standing of each community’s progress with respect to a broad range of social indicators (the metaphorical needles and dials); a formal statement of the priorities of each community (geographic or subject area), and objectives for these priorities; an inventory of successful intervention methods, and accompanying expert commentary to support effective program selection by nonprofits and funders alike; and a full record of government programs and business activities germane to each programmatic area.

What are the Bottlenecks or Impediments to Making This System Function Optimally?

The vastness of a well-functioning knowledge system is clearly daunting. Agreement over what is important or which language to use is elusive. The inclinations of both nonprofit managers and private foundations to “do their own thing,” commission their own duplicative research, operate within narrow communities of practice, fail to share knowledge, and ignore the innovations of others are major barriers. Low data literacy in some quarters and the fast-rising belief that no one will agree on anything, worsened by our inane red/blue political “discourse,” are certainly obstales to consensus. Innovations in the giving and nonprofit management and reporting systems will be needed to compel the actors to build, respect, and make the most of the knowledge system.

What Are the Principal Opportunities for the Innovative Social Entrepreneur?

Many, if not all, of the critical components of the knowledge system are already resident in specific online initiatives as well as in the nooks and crannies of the web. The opportunities presented to the social entrepreneur are information design and online data aggregation. There are many public and private online sources of useful indicator data. The State of the USA already endeavors to assemble and display data in one easily accessible place, together with tools to help understand and visualize the data. The Results-Based AccountabilityTM program has developed tools to help communities (geographic and subject subsector) select priorities, establish objectives, and track progress using these types of indicator data. There are doubtless many other pertinent initiatives. From where I sit, the four opportunities listed below could compel policy-makers and enable their communities, donors, nonprofits, and other agents of progress to access common information, set common objectives, and employ the most effective strategies.

- The expert source. A well-indexed online catalogue (or set of subject-defined subsector catalogues) that would aggregate studies of conditions surrounding and causes for each indicator, evaluations of relevant current and past interventions and programs, and studies of untried prospective solutions.

- The catalogue of social intervention. Designed to complement the expert source, this online resource would catalogue the public, business, and nonprofit initiatives that have implications for each indicator and serve as a primary source of data for strategy development and partner selection.

- Mash-up of The State of the USA and Results-Based AccountabilityTM services (or some similar combination). This is an opportunity to give geographic and subject subsector communities a robust and convenient way to determine priorities, establish objectives for improvement, track progress, and publish all of the above (perhaps to the community objectives catalogue that follows).

- The community objectives catalogue. This online resource would combine and catalogue pertinent social progress indicators with objectives that had been established for every bona fide geographic and/or subject subsector community. They may conflict. Cohesion is a goal, not a prerequisite. The market of resource providers and practitioners ultimately decides. The catalogue enables that “transaction.” In addition to objectives, the catalogue would display the current (and past) value for each indicator. Its purposes would be to focus donor and nonprofit attention on established objectives; encourage collective action; generate new programmatic initiatives that address the documented “sense of community intent”; compel communities to focus on collective objective setting; and encourage greater public data literacy and adoption of a common language for social progress.

The Giving system

The Giving system

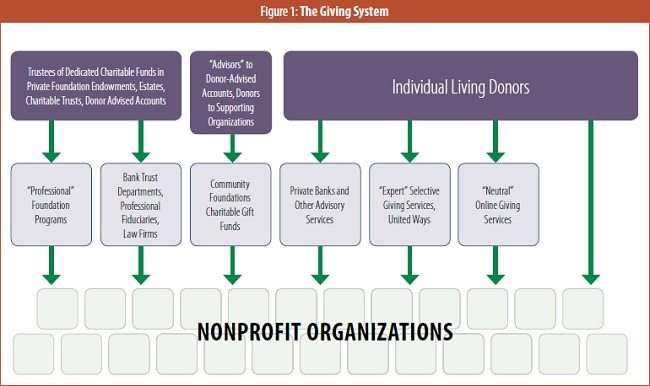

The giving system, as described here, consists of principals—those individuals and trustees who have legal “ownership” of philanthropic assets—and intermediary transaction services, which offer decision, distribution, and accounting support and handle approximately 20 percent of $300 billion in annual giving.

Principals

These individuals have the ability, power, and ultimate responsibility to direct charitable resources effectively. They control donation decisions by giving directly, working through transaction services, or delegating their donation decisions and transactions to expert intermediaries.

Charitable gifts come from over 65 percent of American households. Their gifts totaled $251 billion in 2009, of which only 44 percent went to destinations other than local churches, private foundations, and alma maters—less than $78 billion was directed to disadvantaged people.4 Individual donors seldom seek corroboration of the effectiveness of their contributions, their job being done when they give and claim a tax deduction. In a thriving philanthropy ecosystem, donors will take responsibility for their charitable gifts and demand performance from both nonprofits and intermediaries.

Advisors, typically the original donor to donor- advised funds, comprise an increasingly powerful segment of the donor population.5 Technically, advisors “recommend” to the boards of the host In a thriving institutions that they make gifts from each relevant fund. Practically, they call the shots on grants from over $27 billion currently sitting in such funds.6 With few exceptions, original donors and their heirs can determine the disposition of charitable gifts from their “accounts” indefinitely.

The founding donor to charitable trusts and private foundations can choose to retain control (for him- or herself and his or her heirs) over charitable distributions. Practically, over time, family gives way to independent trustees and institutional fiduciaries. These trustees become legal owners, controlling vast sums in dedicated, generally long-term, charitable vehicles. Like individuals, they have the authority to direct charitable distributions; with respect to the largest funds, they effectively cede that power to professional grantmaking staff, an intermediary role in this construction.

Giving Transaction Intermediaries

Giving Transaction Intermediaries

Much of the country’s giving is conducted through intermediaries that either execute a donor-directed or donor-advised gift or actually determine and execute gifts on behalf of donors. Six models of intermediary activity are explained below.

- The neutral model. This first, “neutral,” model, used by JustGive and Network for Good, is the purest use of the web to facilitate proactive giving by donors. The more knowledgeable, sophisticated, and intentional donors become, the more these services can be integrated with personal accounting and planning services. The higher the quality of nonprofit reporting into such services, the greater the role and value of this model.

- The expert model. The second model, in which a donor gives through an intermediary, guided by experts, to nonprofits of the expert’s selection is a century old. United Ways have long selected portfolios of “winner” local social agencies and distributed donor gifts accordingly. Services that aggregate interesting projects or worthy organizations (e.g., GlobalGiving and GiveWell), or use experts to rate organizations (e.g., Philanthropedia), allow donor choice, but only to a small number of preselected opportunities.

- Advisory services. An industry of formal donor advisory services, a third model, has emerged among private banks, family offices, accounting and law firms, and dedicated donor advisors, each of which seeks to differentiate its services to wealthy clients. The quality of such services varies broadly, but as other institutions enter the field and the industry matures, the potential for greater accountability and competence increases.

- Community foundations. This fourth model has tremendous potential to compel “advisors” to the accounts that comprise the bulk of community foundation assets to be more strategic and intentional. Community foundations have long wrestled with simultaneously serving donors and their own community objectives. The best look for ways to entice donor advisors to be partners in specific community initiatives. The huge charitable gift funds, established by mutual fund companies, make few attempts to promote pro-activity by advisors.

- Trust departments and independent trust companies. Hundreds of thousands of trusts, supporting organizations, and private foundations are effectively controlled by bank trust departments, independent trust companies, and law and accounting firms. In some examples of this fifth model, these institutions serve as trustee and staff. This expansive population of philanthropic institutions is hardly trans- parent and generally ignored in analysis of the nonprofit sector.

- Professional foundation program staff. Calling professional foundation program staff an “intermediary” in this construction is novel. This characterization, the sixth model, reflects the fact that private foundations, with their captive endowments and no need to report to external stakeholders, are largely immune to influence and oblivious to external, or even internal, accountability for the quality of their grantmaking and investment decisions. Professional grantmaking staff often call the shots for the putative owners: the trustees.

Figure 1 (below) depicts the current movement of gifts and grants (green arrows) from donor principals (purple shades) directly to nonprofits at the bottom, as well as through relevant intermediaries (gray shades).

What Is the Importance of This System within the Philanthropy Ecosystem?

Nonprofit organizations often have opportunities to earn revenue through commercial or service activities and may be eligible for government payments for specific services. Nonetheless, philanthropic gifts and grants comprise the stock of capital that nonprofits use to support strategic evolution, new initiatives, and capacity development. The giving system comprises the philanthropy ecosystem’s lifeblood of intentionality, innovation, and responsive capacity. The participants in this system, principals and transaction intermediaries, must take their role very seriously and send informed, faithful, and consistent signals and resources to nonprofit organizations.

What Are the Bottlenecks or Impediments to Making This System Function Optimally?

Donor principals of all kinds are fundamentally unaccountable, which in turn compromises the accountability of the process of allocating philanthropic resources. In general, fulfillment of IRS requirements to realize a tax deduction by an individual or institution, or satisfaction of the statutory payout requirement by a private foundation, is the only auditable “bottom-line” reporting requirement that donor principals have to any external audience. One might expect compensating internal accountability within institutional phianthropies like foundations. However, program staff that effectively make most recommendations for foundation grant distributions recognize that their poor decisions will not impact the foundation fiscally. The same 5 percent of the endowment will be available to them to distribute the following year. As a consequence, foundations themselves have few, if any, effective mechanisms for either external or internal accountability. A philanthropy ecosystem that lacks an accountable resource allocation process is by definition suboptimal. We cannot expect nonprofit organizations to function effectively if donor principals, particularly institutional donors who are looked to as powerful “experts,” are fundamentally unaccountable.

What Are the Principal Opportunities for the Innovative Social Entrepreneur?

There is no shortage of innovative giving-transaction strategies promoted by social entrepreneurs on the Internet, but these efforts will not be valued until donors recognize that they truly have “skin in the game,” and that, as the allocators of financial resources to nonprofits, they must be accountable for their decisions. It is therefore critical for social entrepreneurs to focus on activities that promote accountability by donors, especially foundation trustees, and transactional institutions. Here are some opportunities:

Foundation practice watch. This initiative would evaluate the grantmaking processes of foundations on public websites. The Center for Effective Philanthropy (CEP) has developed methodologies intended to help foundations understand and track grantee satisfaction with their own grantmaking. This is a good start, and CEP staff likely have many thoughts about how to make the foundation sector more effective and accountable through evaluation. However, CEP operates within the intellectual sphere and under the financial boot of the institutions it could evaluate. CEP and existing or new groups like it, such as the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, must be encouraged and independently funded to take on a more incisive role in foundation-practice evaluation. Also, existing or new entrepreneurial agencies should pursue the additional initiatives below.

A center for grantmaking impact. This initiative would evaluate foundation programs on their effectiveness, the quality of their reporting, and the congruence of their grantmaking strategies with community needs and goals, and report such findings on a public website. In a bid to encourage internal and external accountability in private foundations, the center would view trustees as a principal audience for this work product, encouraging them to demand more from program staff.

New intermediary grantmakers. If trustees of foundations remain dissatisfied with the conduct of their resident program staff, they should utilize the services of other grantmaking institutions to manage all or a portion of their annual grantmaking budgets. Social entrepreneurs could remake the grantmaking model to be more efficient, effective, and accountable, and sell that service to endowments and wealthy people. Such services would enable the necessary separation between endowments and grantmaking, and establish a degree of accountability unattainable in our dominant private foundation model.

Foundation worthiness calculator. The strategies above would improve the internal accountability of foundations, but until foundation trustees become accountable externally for the activities and decisions of their institutions, we cannot expect the giving system to perform optimally. Today, accountability for trustees begins and ends with proper fiduciary conduct. A service that would not only reveal the effectiveness of the grantmaking program of a foundation but also report on each foundation’s institutional strategy to maximize the value of its capital (e.g., more rapid payout, mission investment of endowment, collaborative grantmaking with other foundations, use of multiple grantmaking intermediaries, etc.) would have considerable, highly leverageable value for the entire philanthropy ecosystem.

Catalogue and evaluations of the donor-advised fund programs of community foundations and major charitable gift funds. This entire field would benefit if a new service were formed to review the value propositions offered by each of these transaction intermediaries. These intermediaries have the potential to become highly productive forces in the education of donors and the accountability of the giving system, but no external party is watching, evaluating, or reporting. A new evaluative service could assess the degree to which each intermediary provides its donor advisors consistent reporting by nonprofits, nonprofit performance tracking information, pertinent knowledge from the environmental knowledge system, and other support to become more intentional and discerning donors.

Notes

- As this article presents just the first half of the paper, the nonprofit management and reporting system and the nonprofit evaluation system are not discussed here; they will be elaborated on in NPQ’s upcoming fall 2013 edition.

- In an interview with the author.

- See note 1, above.

- The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University, Giving USA 2010: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2009 (Chicago: Giving USA Foundation, 2010), 6–9.

- Donor-advised funds are hosted and are technically owned by community foundations and charitable gift funds.

- Ben Gose, “Charities Can Expect More Money to Flow from Donor-Advised Funds,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, July 11, 2010.