December 19, 2017; Next City

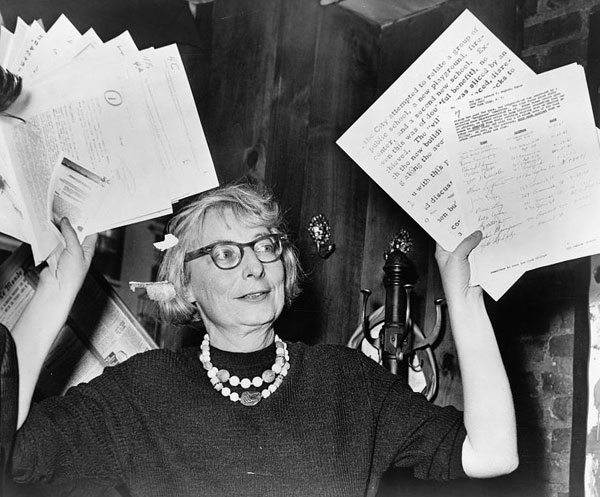

The most famous name in urban planning is Jane Jacobs, yet women’s voices still are often buried, notes Katrina Johnson-Zimmerman in a thought piece for Next City.

Evidence backing Johnson-Zimmerman’s observation is not hard to find. For instance, the 2016 edition of Routledge Press’s City Reader has 66 named contributors. Yet as its table of contents shows, 62 of those contributors are men. (The four women to make the cut are Jacobs, Saskia Sassen, Daphne Spain, and Sherry Arnstein.)

Johnson-Zimmerman also decries “the maleness of the pop urbanism circuit… To name a few: Richard Florida (Creative Class), Jeff Speck (Walkability), Fred Kent (Placemaking), Jan Gehl (Cities for People), Gil Penalosa (8 80 Cities), Andres Duany (capital-‘N’ New Urbanism), Mike Lydon and Tony Garcia (Tactical Urbanism).”

Planetizen is a leading urban planning site. Its “top 20 urban planning books of all time” list includes only two books by women: The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs and Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. Both are classics, but both were written over 50 years ago. One might ask, haven’t women written any significant urban books since? (Answer: Of course. To pick one prominent omission, Saskia Sassen’s highly influential The Global City merits consideration).

There are some signs of progress. Certainly, the fact that only 17 of 100 of Planetizen’s 2017 “most influential urbanists of all time” are women still falls well short of equity, but it does represent progress from the nine percent when the list was last compiled in 2009. Planetizen observes, “Urbanists are becoming more aware of the essential contributions of women and people of color throughout history and in the present, but we have a long way to go to achieve equal standing for all people in the built and natural environments.”

In any case, Johnson-Zimmerman is certainly on the mark when she points out,

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

If Jane Jacobs always tops the list of urbanists, then—pardon the expression—where my ladies at? Suzanne H. Crowhurst Lennard, for instance, was in the room with the pioneers of urbanism, as was Margaret Mead, the famous cultural anthropologist and compatriot of Jane Jacobs. Where are they on the list? Mindy Fullilove literally wrote the book on the mental health impacts of urban renewal, displacement and segregation yet her work is missing from many contemporary planning anthologies. Tamika Butler drives the diversity and cycling conversation with refreshing honesty and experience. Likewise, Lauren Elkin’s recent book Flâneuse added a previously nonexistent feminine version of the masculine word for “urban wanderer” to our lexicon.

What to do? One step that Johnson-Zimmerman advocates is signing onto a list, which over 1,000 have already done, in which signers commit to not participating in all-male panels. A broader challenge, of course, is to change urban planning practice. Another step, already under way, is changing the demographics of who is an urban planner. The National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) reports that “42 percent of graduates in architecture were women (not too shabby for a field that banned women from becoming licensed architects until 1972 in some cases), while 52 percent of urban planning graduate students in 2016 were women.”

Lynn Ross, former vice president of Community and National Initiatives (CNI) program at the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, remarks:

If you have the same people around the table who have been trying to solve the same challenges for 50 years, nothing will change. I think it’s important to have women not only at the table, but women running the meeting, setting the table, bringing voices in and leading. She has a variety of perspectives, as a caretaker, as a mother, as a sister, but also—she’s an urbanist—and she has something to say about cities and how they work.

Ada Colau, the first female mayor of Barcelona, observes that with the rise of women in leadership and urban planning roles, “right now we have an opportunity for those individuals who have traditionally been let down as ‘second-class citizens’ to become the main characters.”

“One thing is clear,” Johnson-Zimmerman concludes. “When we increase diversity in the conversation, we improve our fundamentally heterogeneous, intersectional, and always evolving urban environments. If we are to tackle our urban future with the full abilities that humanity has to offer, we’re going to have to add women of all ethnicities and experiences to that list.”—Steve Dubb