This article was published in the Fall 2012 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “Nonprofits & Democracy: Working the Connection.”

How should healthcare be reorganized? How should the economy be reorganized? How should journalism and food systems be reorganized? Nonprofits could and probably should be a dominant voice responding to the challenges of our new knowledge economy. Why? Because our tradition of mobilizing people to work together for shared value and of working noncompetitively in networks or value chains matches well the ascending modes of productive endeavor throughout our economy. These traditions comprise elements of a significant strategic advantage for nonprofits doing the work of society. But this advantage is not God-given or perpetual—it requires focus, constant development, and a serious emphasis on mutual benefit and the common good. I ask readers to take this paper in the spirit it is written, as a partially-formed collection of thoughts—a provocation that can be much improved upon.

Strategic Advantage? How Does This Apply to a Nonprofit?

Simply put, a strategic advantage is anything that makes you more successful than others at what you do in your chosen space. An organization can achieve such an advantage through developing “an attribute or combination of attributes that allows it to outperform its competitors.”1 This article is about how nonprofits have significant strategic advantage but are functionally blind to it because they don’t recognize or use it. This blindness could cause the civil sector to lose its opportunity to become more influential in the world’s future. Even in this country we are seen as the least dominant of the three sectors, but that may be because many nonprofits have parked their power in the attic, where it is gathering dust and atrophying from disuse.

After decades of discourse about how nonprofits need to be more businesslike, I am driven to discuss the differences structurally and in more detail. The admonition to be more like a business is a preposterous proposition—ill informed and exhibiting a sloppy state of mind that tries to draw us all off track to a space of unaccountability. Don’t fall for it. For goodness’ sake—if you want to act like a business, be a business! The major distinguishing factor of a business is its ability to build the wealth of individual owners rather than build collective well-being and value. Decide which bottom line you are dedicated to, and make it your own.

The fact is that while we have been wasting time looking in other directions—having been admonished away from our native DNA—business theorists have been noting that what we as nonprofits have in our tradition of association and collective endeavor is what this next era of value-producing enterprise needs. Just to put some of the underlying precepts away, being a nonprofit does not equate to financial and managerial incompetence, and being a business does not guarantee efficiency or results. There are lots of badly run businesses—probably in sheer numbers many times more than there are badly run nonprofits. Do most people care that they are badly run? Not really, if they have choices in the market. And, in theory, the only reason why we should care if a nonprofit is badly run is because it gets subsidized by us. But wait—does this assume that businesses are not subsidized? Of course, we know that they are and that some of them—even while being very well subsidized by our government—have gone ahead and violated the trust of their stakeholders profoundly.

What I would like to propose is that we think differently about all of this. There is more that is alike about for-profit and nonprofit organizations than is different, but there are core differences in our traditions and purpose that could constitute a strategic advantage for many nonprofits—if we claimed them. We should be making those distinguishing characteristics work for us in a more conscious and powerful way, because we are looking at a world that needs a different dominant paradigm than one that judges success by how much money we can make—the future of our grandchildren be damned!

Co-creation and Democracy: A Natural Link

In The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers,2 C. K. Prahalad, one of the more influential management thinkers of the past generation or two, and Venkatram Ramaswamy held that the traditional relationship between firms and consumers was becoming obsolete. It was being replaced by a system whereby companies engage their publics in a more personal way to “co-shape the future” of the enterprise and craft the experience of the encounters. The authors say this causes tension at every point of intersection. It sometimes gets uncomfortable and messy—like democracy. It also produces innovation and tailoring, and works against the alienation of customers. Some businesses already clearly understand these interactions as a distinguishing core of their business models.

Nonprofits could have an enormous advantage in attracting people to this paradigm, because our ability to appeal to common cause and individual aspiration through activity aimed explicitly at common benefit is a natural magnet for engaging the energy of stakeholders. (The caveat is that this is true only if you view those stakeholders’ energy and intelligence as more valuable than rubies.) We also have in our midst community-organizing skills, and these are useful in thinking about how to help communities organize themselves to get things done.

Working the Concept of Reciprocity

Another advantage that nonprofits ought to be availing themselves of is our stakeholders’ unpaid/volunteer labor. This is an advantage of some enormity. Wikipedia would not exist without it. Even though people might love to tweet about the latest burger at a fast-food emporium—and that is, in fact, unpaid labor in the marketing arena—they are less likely to be willing to work at a counter for free. Nonprofits can use volunteers in any number of roles in which they are currently using paid staff—allowing for streamlining of some sorts of operations or expansion without unbearable cost. This advantage is, of course, linked to other resources that add to sustainability and effectiveness. In particular, happy volunteers in an agency lead to more traction in fundraising from stakeholders.

But let’s go back to cost containment for a minute—cost of operations is obviously a consideration of great import for a business or a nonprofit. If we knew that we could contain personnel costs—which is the largest cost category for many nonprofits—through approaching the engagement of supporters in a more active way, why would we not fully explore it? Yet many nonprofits do not have an active “volunteer” program that is part and parcel of their business model. And the word volunteer does not even do justice to the leadership and risks that have been and are daily taken by individuals in this sector who feel passionately enough about a cause to put their hands to it.

The ties that bind, of course, are shared values and a collective aspiration, whether they be short- or long-term. Again, the principle is not exclusive to nonprofits; the authors of a 2003 paper, “Focusing on Value: Reconciling Corporate Social Responsibility, Sustainability and a Stakeholder Approach in a Network World,”3 write, “long-standing assumptions about how to maximize the effectiveness of a firm (as measured by traditional metrics such as profits or economic value added) have been tempered by the novel recognition—at least in some quarters—that in certain circumstances the creation of communities and social networks united by a common sense of what is valuable is a pre-requisite to economic pay-off.”

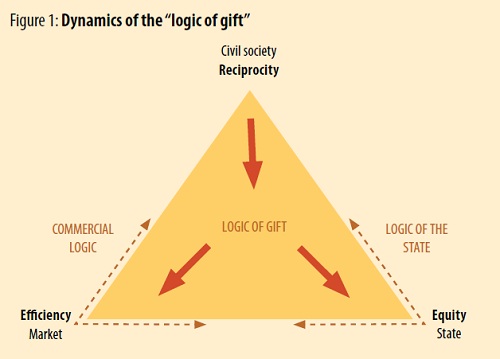

Wolfgang Grassl takes this on explicitly in his paper “Hybrid Forms of Business: The Logic of Gift in the Commercial World.”4 Though based on papal teachings and aimed at informing social enterprise design, it advocates for a “logic of gift” in economic activity, and that logic is based on reciprocity (see figure 1, above). He adds, “Gift-giving is possible in a multiplicity of forms, all of them having the power of building relationships transcending mere exchange.” Where equity is the logic of the state and efficiency is the logic of the market, reciprocity, he notes, is the logic of civil society.

But do nonprofits work this logic of reciprocity in the same way that business works the logic of the market? I would suggest not. And we have lost our focus at a time when that focus would be very useful in dominating discussions about global well-being.

Just to take this one step further, some of the writers about the competitive advantage provided by co-creation do remind us that the reciprocity is not between the firm and the stakeholders but between stakeholders using the firm as a vehicle for the outcome they want. This is the contract. As the people in your community network, stakeholders inform and embolden each other to act and speak out. If this scares you, you have a lot of work to do in refitting your organization for the future.

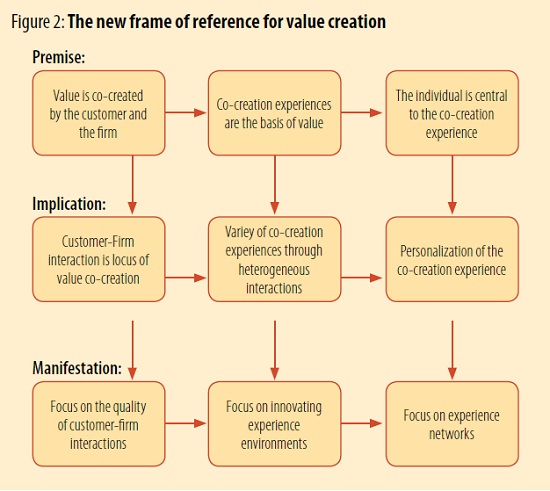

Figure 2 is a new frame of reference for value creation,5 as shown in Prahalad and Ramaswamy’s aforementioned book The Future of Competition, in which they describe the “building blocks of co-creation” as dialogue, access, risk assessment, and transparency. Each of these must be committed to and experimented with to produce a new core set of daily habits. We liked an example the authors advanced of the use of dialogue and access in the world of entertainment: “To promote the mega-hit movie Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring New Line Cinema reached out to the more than 400 unofficial fan Web sites, giving them insider tips, seeking their feedback on the details of the movie and offering them access to the production team.” Tolkien’s literature is known for its passionate enthusiasts, so this could not have been a wiser move. It made stakeholders feel “a part of it” and it engaged their intelligence on development, but we have seen over and over again nonprofits that do not think they need to check in with their own passionate enthusiasts when they get ready to make decisions that people might care about. This is what causes stakeholders to become dispassionate, disengaged, or even so angry they publicly take the enterprise to task.

But why might the fit between the co-creation idea and the business sector be more awkward than with the nonprofit sector? Because, although this kind of crowdsourcing does engage those who make use of it and then guide the organization in tailoring a product to them—thus building their loyalty to the product as ambassadors—the financial value of the outreach does accrue to the producer and not to the network. (There may be additional allegiance to be gained in a system that allows co-creators to share in the financial return of an enterprise, as well.)

Relationships and Networks

The F. B. Heron Foundation’s statement on its website, headlined “The World Has Changed and So Must We,” is a striking one.6 Heron is focused on the economy, like many others, but declares that it must be addressed unconventionally. “We must acknowledge the need to rebalance the economy itself so it can deliver value on America’s traditional promise: full livelihood, democracy and opportunity for all. Investing in the building blocks of that economy and assuring the basics of entry is a critical responsibility, not only of philanthropic institutions and government, but of banks and businesses. We believe we can realize an economic vision for a more universally prosperous society, one that supports democratic pluralism and civic vibrancy, provides dependable work for adequate pay, protects the most vulnerable, and competes successfully globally.” Big ideas, but how might we as local entities really take such stuff on seriously? We think that it is through deep local engagement and network development.

Some of the literature we read regarding co-creation takes on the aggregate value of one’s own immediate network—and the networks associated with them—as an extended resource base that allows ideas to come to fruition. A paper discussing Corbin Hill Road Farm Share, a hybrid food value chain, describes pretty succinctly what the nonprofits in the chain brought to the table:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Nonprofits bring to the value chain social capital that comes from the networks, mutual goals, trust, and beliefs that nonprofit organizations share with their members and stakeholders. This social capital, the ability to engage community members, raise funds, disseminate information, and reduce transaction costs, has significant financial value.

Nonprofits can help companies to aggregate and channel demand, lowering transaction costs. Their staff members often have organizing skills that enable them to reach out to and attract customers. Nonprofit partners may provide critical insights into the needs and constraints of low-income consumers . . . and through this knowledge can help in the maintenance of a customer base. Nonprofits also tend to be located within the communities they serve and so have a first-hand understanding of the logistical issues associated with local business development.7

Hybrid food value chains, state the paper’s authors, function through co-creation of value accruing fairly to the interests of all. Anyone who has worked in this sector knows that this is all hard stuff. But when you do not take seriously the fact that the negotiation of relationships will be filled with tension, energy, and possibility—as well as pain—you have bowed out of the twenty-first century.

Relational Value—Not the Soft Stuff, the Hard Stuff

Okay, so those are the risks if you do not engage your stakeholders deeply in the development and implementation of the organization’s work, but how are we to understand the benefits quantifiably? The authors of a 2010 paper, “Undervalued or Overvalued Customers: Capturing Total Customer Engagement Value,”8 suggest four ways to determine the value of one engaged customer:

- Lifetime value in terms of transactions;

- Referral value;

- Influencer value; and

- Knowledge value.

(We would actually place the second and third, as they state it, in one category, and add “Critical mass for offense as well as defense.”)

So here is how trust-based, long-standing relationships would add value to civil society organizations over time within these categories:

Lifetime value in terms of transactions. This would include donations of cash and time as well as fees paid directly or indirectly because of that individual’s participation.

Referral/influencer value. This would include the person’s willingness to carry the message of the organization and attract others to the community that both fuels and benefits from it. It also includes influencing other resource points, like foundations or government. It may include policy advocacy of one kind or another and attachment of other networks with which the person is involved—and, by extension, with which people in those networks are involved.

Knowledge value. This would include the person’s observations about the context in which you are working, the direction you are taking, and other information that may be challenging—even disruptive—or otherwise useful.

Critical mass for offense as well as defense. This would include making the community heard if the effort is pursuing a non-dominant strategy or point of view, or if it is attacked politically or otherwise—but again, this is deployable only if your community is convinced that you are acting with integrity and transparency. (Think Planned Parenthood vs. Komen.) The extension power of this type of system can be mobilized quickly through so-called value-based networks. This integrity and transparency thing is a difficult standard to bear, but perhaps less difficult than secrecy and a lack of accessibility—especially if you are supposed to be working for the benefit of the public.

Building the relationship between your effort and community does not happen en masse anymore unless you have a monopoly of some kind; nor is it a single transaction, as in something offered and accepted that leads to a loyal relationship. Maintaining a community that keeps giving requires interaction where what you are doing is continually tested for its responsiveness and fit. If you can turn this corner out of the organization-centric dead zone, it will lead to collaborative action and eventual transformation of practice.

Babies Claiming Neglected Birthrights

Some organizations, of course, have been founded in the new image. David Karpf discusses a few of them in his new book, The MoveOn Effect,9 in which he contrasts the large, expensive, professional political-advocacy organizations that were the standard a decade ago with some of the current smaller, nimble, but powerful online-based advocacy groups with “absurdly” small budgets by comparison. These groups sometimes only provide the infrastructure for their values-convened community members to take action. Karpf is clear that one is not a replacement for some of the activities of the other, as in litigation; but the long-standing rift between national advocacy groups and the communities that they are supposed to represent can no longer be bypassed with enough checkbook members with overstuffed wallets. It is a different and disrupted accountability environment for national advocacy organizations, and it promises to become only more so.

The Role of Trust and Credibility

Don’t be dishonest with your constituents, because it will preclude your being this new, superfueled type of organization. Don’t promise them things that you can’t deliver. Be clear about how you make decisions that affect their experience of the community and the organization, and on what basis they are made. Your brand is no longer what you decide will be presented to the public; it is the public’s experience of you, drawn from multiple interactions during which you are tested and from other reports from members of the community.

So the brand now exists in the interaction or, more measurable, in how well your community can express who/what/how you are to them and the world and the issue on which you work. Many nonprofits are blessed with a halo effect as a mission- rather than profit-focused organization, but that also means (1) a fall from grace may be a fall from a greater height than your own behavior called for in the first place, and that can be a shock; and (2) a violation of trust will hurt other civil society organizations around you, and your networks will be disrupted. People won’t necessarily want to be seen with you, and this puts you in a serious social capital deficit.

Changing of the Guard: Why Is This Shift So Hard for Some?

Prahalad and Ramaswamy, while recognizing that co-creation was the wave of the future, assumed that there would be many firms that would not be able to make this shift because they would be unable to come to terms with the ways in which it challenged the traditional roles of purveyor and consumer. They acknowledged the tension that is created in a new, more open system:

The disconnect between consumer think and company think is not new. However, as we move toward co-creation, this disconnect becomes more pronounced at points of interaction, those intersections where choice is exercised and the consumer interacts with the firm to create an experience. . . . Managing the co-creation of unique value demands a new capability: the ability for managers to relate to consumer interactions with the experience network. Managers must increasingly experience and understand the business as consumers do, and not merely as an abstraction of numbers and charts. To co-create value effectively, managers must also have the capacity for agility. Agility is the ability to act fast—to improve the cycle time for managerial action.

And those characteristics must become core management tenets, because “agility depends above all on the readiness of the line managers to respond quickly to changes on demand.”

In Conclusion

The advantages of being community based are more cheaply had than ever before. They can be more quickly and dramatically used, and they promise more influence and effectiveness and reach than ever. But they can only be had with personal commitment to their value.

The investment is in the faith placed in those with whom you are in common cause. The integrity with which you approach that relationship is your coin of the realm—it buys you more confidence, donated labor, intellectual contributions, and ambassadors than the other two sectors. The investment is far from transactional but there is give and take—with trust flowing in both directions. Promise and don’t deliver, contract to listen but remain deaf, refuse to share decision making and violate your stakeholders’ sensibilities with no, or a weak, explanation, and you are headed into bankruptcy as a nonprofit—you have relinquished your advantage and distinction. In short, we are re-approaching our nonprofit traditions as nodes of democratic activity when it seems like the reins of our communities’ futures have slipped from our individual hands. And that is a position with powerful potential for success or failure, but the outcome will be of your choosing.

Notes

- Definition of Michael Porter’s theory on competitive advantage.

- C. K. Prahalad and Venkatram Ramaswamy, The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers (Boston: Harvard Business Press Books, 2004).

- David Wheeler, Barry Colbert, and R. Edward Freeman, “Focusing on Value: Reconciling Corporate Social Responsibility, Sustainability and a Stakeholder Approach in a Network World,” Journal of General Management 28, no. 3 (Spring 2003): 1–28.

- Wolfgang Grassl, “Hybrid Forms of Business: The Logic of Gift in the Commercial World,” Journal of Business Ethics 100, supp. 1 (2011): 109–123.

- This graphic was reprinted with permission from Venkatram Ramaswamy.

- “The World Has Changed and So Must We: A New Approach,” the F. B. Heron Foundation.

- Nevin Cohen and Dennis Derryck, “Corbin Hill Road Farm Share: A Hybrid Food Value Chain in Practice,” Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 1, no. 4 (Spring-Summer 2011), 87. Copyright 2011 by New Leaf Associates. Reprinted with permission.

- V. Kumar et al., “Undervalued or Overvalued Customers: Capturing Total Customer Engagement Value,” Journal of Service Research 13, no. 3 (August 2010), 297–310.

- David Karpf, The MoveOn Effect: The Unexpected Transformation of American Political Advocacy (New York: Oxford University Press USA, 2012).