January 30, 2018; New Yorker

The New Yorker published a story yesterday revealing that Gar Alperovitz was a key member of the Lavender Hill Mob, the loose group of anti-war activists that helped to hide Daniel Ellsberg for three weeks as they released the Pentagon Papers to various news organizations.

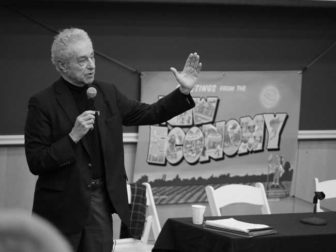

The article describes the first meeting between Alperovitz and Ellsberg at a dinner party and the subsequent weeks when the group contacted reporters and delivered documents. While Ellsberg now credits him with “all the cloak and dagger stuff,” Alperovitz, now 81, says the whole endeavor was entirely uncharacteristic of him, but he felt responsible for trying to help stop the war.

I was someone who was trying with many other people to stop this killing. It was a moral issue of the first order.

“I’m a very cautious person,” he comments, “but I didn’t blink—which I don’t understand. I’m surprised I didn’t just say, ‘whoops, I’m busy tomorrow.’ It was out of character.”

Meanwhile, the article describes a made-for-screen series of elaborate handoffs of an estimated 7,000 pages of material, orchestrated by Alperovitz and his colleagues.

The story has been told before, but with the names undisclosed. For example, the initial stages of the handoff of the Pentagon Papers to the Washington Post—now the focus of a motion picture starring Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks—is described here:

The next morning, in the newsroom of the Washington Post, assistant managing editor Ben Bagdikian stepped out of a meeting and was handed a slip of paper. He read the short note:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“Call Mr. Boston from a secure phone.”

The name sounded fake. There was a phone number with a 617 area code. Boston. Bagdikian thought he knew what this might be about. He ran out of the building and across the street to a row of pay phones. He dropped in a coin and dialed the number on the note. Someone picked up.

“An old friend has an important message for you,” a man’s voice said. “Give the number of a pay phone where the friend can call in a few minutes.”

The Boston Globe, the less-famous third paper to print the Pentagon Papers, also recently told a similar story:

Then-editor Tom Winship was contacted by someone who identified himself as “Mr. Boston” and offered to provide the documents, wrote Storin, who had just left the paper’s Washington bureau to take up duties as metropolitan editor in Boston. Because Storin had reported from South Vietnam earlier that year, Winship tapped him to join other editors and reporters in an out-of-the-way conference room on another floor of the paper’s Dorchester headquarters.

[Storin added] “Two editors were instructed to stand by phone booths in Cambridge and Newton. The Newton ‘drop’ was the fruitful one, and Tom Ryan, national news editor, walked triumphantly into the Globe with a red plaid zipper suitcase full of Pentagon Papers excerpts.”

Alperovitz has written extensively on the atomic bomb and atomic diplomacy, and he remains a leader among leaders in conceptualizing and helping to spark models of a more pluralistically owned and controlled economy.

As for why he’s coming forward now? He sees the political climate under Trump as very dangerous, as rhetoric with North Korea grows both outrageous and destabilizing, and this moment as one in which it is important to act decisively and with moral certitude because it is the right and necessary thing to do.—Ruth McCambridge