It is well known that the quality and the depth of organizational leadership affects many things in an organization—not just outcomes, but also reputation, integrity, innovative capacity, flexibility, and revenue. Today, when nonprofit leaders and emerging leaders are already stretched past their capacity, the idea of pulling them out of their work to engage in leadership workshops may seem like an indulgence. And yet there are critical “learnable moments” in the work of nonprofit leaders, many of whom have extended into new territory to keep their organizations not just alive but powerful in an unpredictable environment. How can we make the most of this opportunity?

Over the past five years, Community Resource Exchange (CRE) in New York City has run a leadership development program anchored in the real workplace-related problems people are trying to solve. The program focuses on helping leaders hone their reflective capacities, make use of peers as consultants, and practice the implementation of real change in their own organizations. The basic model includes the following components:

- issue-based sessions on leadership topics;1

- facilitated small team problem solving (or action learning);

- support from a 360-degree feedback opportunity (and individualized coaching when resources are available); and

- a one-day extended case, or management simulation.2

What We’ve Learned

Caucus participants have been able to survey their leadership style, organizational needs, and field standards to perfect their leadership capabilities. One participant notes:

The CRE Leadership Caucus has [enabled] me to do more than . . . look at the needs of my agency, the demands of my constituents, and the standards set by the field. It has encouraged and challenged me to examine myself as a leader and to determine what kind of leader I am and will aspire to become. The 360-[degree] evaluation, our small groups, the simulation, and several training sessions helped me. . . . I realized how difficult it is for me to have difficult conversations with employees and how I set myself up for burnout by not holding others accountable for their responsibilities or the same level of excellence. I learned that I can be aggressive and demanding of myself and no one else and that this is counterproductive in many respects.

In 2009 we launched a formal evaluation study3 to answer questions that have driven the development of the Leadership Caucus: “Can a leadership development experience create positive change in leadership practices and even organizational effectiveness? What about the experience makes the difference?” The study involved the first five cohorts of 88 leaders who completed a caucus between 2004 and 2008.4 (To date, 150 nonprofit leaders in seven cohorts have completed a caucus. The evaluation study focused on the first five cohorts.) Since the completion of the study, the findings continue to be corroborated with participant feedback from the sixth and seventh caucuses.

There are several key takeaways about what works and why. Some of the lessons learned affirm our initial hypotheses; but other findings were unexpected.

- A caucus is greater than the sum of its parts. More than simply providing variety and accommodating different learning styles, the multiple learning methods are critical to the caucus’s high impact for several reasons:

- multiple learning methods reinforce one another in unexpected ways;

- one mode provides the opportunity to implement something learned in another (for example, action learning provides the space to “try” something learned in an issue session or a simulation);

- together, the four methods create a “reflective, learning space” and a rich learning environment; and

- no single aspect of the caucus could have had the impact of the many parts taken together.5

- The duration and frequency of sessions are critical, but not for the reasons expected. A peer group forms quite readily, but the duration allowed relationships of a certain depth and quality to be made. Groups continue to meet informally and formally after the conclusion of the caucus.

Length gave participants the opportunity not only to make personal leadership changes but also to make changes at the organizational level with peer support. Participants felt supported to take risks. Eighty percent implemented some organizational-level change, most successfully. This was especially gratifying, because changes in organizational performance are the highest-level changes envisioned in the study and something we were not sure could be achieved.

Duration gave participants the opportunity to be debriefed and receive feedback in real time so that they had more than one chance to practice new behavior.

Participants reported that they learned by doing, tried new behaviors, and received reinforcement and feedback from peers within the caucus. Peer networks emerged naturally because of shared experience in a safe, facilitated setting. Participants cited connection with others as an antidote to feelings of isolation in their leadership roles. They also noted that practical problem-solving exchanges with peers were essential in risk taking within their organizations following the caucus. - Program design matters. While the Leadership Caucus’s methods are not uncommon in the field of leadership development, the mix and structure is an important factor in participants’ reported success. The opportunity to try and practice new behaviors is as important a design ingredient as providing best practices information. Key takeaways were the following:

- design assumptions correctly anticipated that adults learn better by sharing and doing;?

- learning from other participants was sometimes more powerful than learning from facilitators;?

- issue-based sessions, most like a “workshop” format, work best when they are (1) highly interactive and (2) designed as a staging point for other caucus components. This prompted us to add more time for small-group exchange within issue sessions and a short action learning session at the end of each issue session;?

- As mentioned previously, the program design reinforced methods in unplanned ways. One caucus component provided the opportunity to explore something that was triggered in another component.

- Prior relationships and familiarity with organizations are vital for developing the caucus. These relationships are invaluable in attracting participants eager for the growth opportunity and for whom the leadership issues are relevant. Hands-on and early involvement with outreach and vetting of candidates was critical in recruiting busy, sometimes-skeptical leaders to participate and grouping these leaders into appropriate cohorts.

- Workshop-like sessions triggered change. Of the four methodologies, the issue-based session is closest to the classic workshop format, which the literature reports as not having produced the greatest impact. Yet the issue-based sessions in the Leadership Caucus triggered greater change than anticipated. We believe this is because of the relevance of the topics, which focus directly on participant experience and the day-to-day realities of leading a nonprofit. Further, the session topics serve as the “staging point” and work well with other caucus components.

- Readiness is a key factor for successful participation. “Low impact” participants—those for whom the caucus program did not significantly change behavior—cited the following reasons for their inability to sustain gains from the caucus: their preferred learning style (individual versus large group setting), some design and facilitation aspects not aligned with their learning style, and their inability to make the time commitment needed for the caucus.

The evaluation data reinforced our experience that the Leadership Caucus works well. One key finding was that a high percentage of respondents—88 percent—report reaching three out of four outcome levels: heightened awareness and insight into their leadership challenges; increased confidence and desire to address leadership challenges;? and changes in their own leadership practices. One participant was humbled and empowered by her self-discoveries: “The caucus has given me reason to . . . honestly [look at] what I’m doing, why, and how. The ‘aha’ was . . . in accepting the need to just stop sometimes. In a position where I’m constantly assessing the work product and management style of subordinates, I don’t do enough self-assessment. [The process] validated some of my greatest strengths while pointing out weaknesses that I’d too frequently dismiss.”

Another key finding was that 80 percent of participants have begun to make effective changes in their organization, which includes self-identified “small” and “large” changes. This is important. Implementing organizational change is the most difficult outcome to accomplish and measure. The result is, therefore, a meaningful indicator that the caucus has helped participants make organizational improvements. In the words of one participant: “Fueled by the ideas presented, [my board chair] and I . . . initiated a board retreat to discuss and develop a long-term vision and an outline of future strategy. . . . Everyone on the board very much welcomed this opportunity to stabilize and focus on our upcoming tasks and challenges.” Another participant reports that his organization’s policy advocacy efforts were enhanced by strategies discussed at the caucus. “I followed through on these recommendations, and it has led to positive outcomes. Staff members are now much clearer on our strategic direction. . . . [They] are thriving, and one staff member who was resistant about this strategic direction . . . has begun to take the initiative to speak at public hearings and meet with other advocates.”

Because the results are promising, the Leadership Caucus retains all the basic elements of the original design: issue-based sessions on leadership topics, action learning, a 360-degree feedback opportunity, individualized coaching when resources are available, and a one-day management simulation. The eight-month format remains highly interactive, grounded in the latest leadership development theory, and anchored in the realities of community-based organizations.

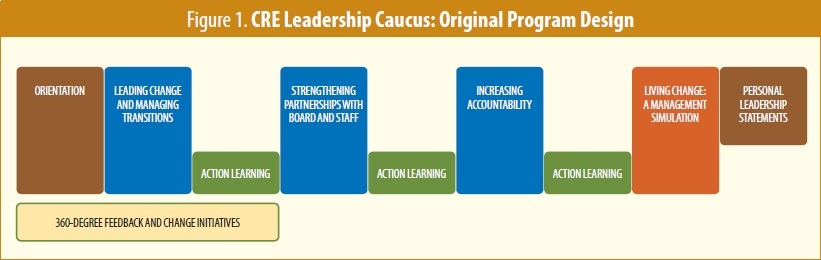

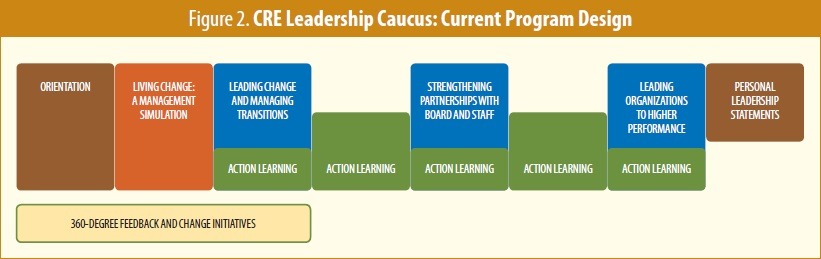

Figure 1 shows the design of the Leadership Caucus for the first five caucuses; figure 2 features the current design. Although the original design worked well, we tweaked the caucus for quality improvements, including making sessions more participatory and further enhancing real-time problem solving and peer exchange. As part of continuous improvement, we moved the simulation earlier in the caucus, consolidated issue sessions, and added time for action learning at the end of full-day issue sessions.

Program Enhancements

Inevitably, we considered other changes that could improve caucus impact. The following ideas are based on feedback from participants as well as on our own experience of what works:

- Coaching, coaching, coaching. During the caucus, the 360-degree feedback session was followed by coaching for a few cohorts where funding was available. Our findings indicate that such coaching is transformational. One caucus participant learned from his 360-degree report that he hadn’t adequately shared his vision for his organization’s future with his large and dispersed staff, which had affected morale and motivation at a time of rapid change. Through coaching, this executive worked with a CRE consultant to identify practical ways to transmit his vision to the rest of the organization and test reactions. They devised mechanisms to convey vision, such as a regular newsletter column and a “big picture” moment at the beginning of key meetings.

Increasingly, we have received requests for leadership and management coaching as part of the caucus or as a standalone engagement, which suggests that executives find this mode of personal development effective. - Follow-up. Organized follow-up after completion of the program may be key to sustaining the gains. Participants have consistently suggested affordable and relatively simple follow-up events. One participant corroborated this feeling: “I’ll miss sitting among my peers in a setting where collaboration and shared learning are the common goals. I’ll miss having the time and the space to separate myself from the frantic pace of my typical day to reflect on what I’m doing right and how I can do it better.”

- “I wish my board chair were here.” During the caucus, we often hear about the need to bridge the board–executive director partnership and to address the leadership challenges of boards. Effective board leadership is critical to the health of organizations but—when it comes to practical capacity-building opportunities—relatively neglected.6

Implications for Nonprofit Leadership Development

The challenge for the nonprofit sector is to act on knowledge about what works. This article describes a unique leadership development program that is ready for replication. The results cited here make clear that a leadership program with the key elements we describe7 can affect leadership practice and organizational effectiveness. Since the impact of traditional, one-off workshops and seminars is known to be limited, more must be done to establish robust learning environments as the norm for leadership development for nonprofit organizations. We would like to see comprehensive leadership development initiatives move beyond the status of nice-to-have to become a supported, pivotal part of the nonprofit sector’s commitment to organizational growth and development.

As critical as leaders are in moving organizational agendas forward, they cannot do so alone. They need their boards and teams to develop strategies and mobilize action toward goals. If boards and teams share a common leadership perspective, we could shore up their efforts. To this end, in November 2009, CRE launched a board leadership caucus. But the sector still needs to bring this leadership development experience deeper into organizations’ management ranks.

Sustainability is the other big question mark. How well can participants sustain their gains without further support? Participants have suggested post-caucus follow-up events consistently. When a follow-up was made available to the cohort of deputy directors, the impact was noticeable. Some have become executive directors or have taken on greater management responsibilities. What can the sector do to provide high-quality, effective post-program follow-ups at relatively low cost?

CRE is ready and willing to play a role in the growth and dissemination of such high-impact learning models, including partnering with other providers to implement a leadership caucus or related offering. In a world of hard times and unpredictability, nonprofit leaders are—now more than ever—one of our sector’s most important resources. They deserve our creativity and support.

NOTES

1. All caucuses included a similar palette of half-day issue-based sessions on topics such as moving beyond managing to leading, managing transition, building a talent bench, and using data as a management tool. Funder-specific caucuses included topics such as facing the challenges of race, gender, and class differences; fundraising and fiscal management; and strategic planning and management. Half-day sessions have been consolidated into interconnected morning and afternoon sessions spread over three full discussion days (see figure 2). A first day is devoted to leading change, a second day to building stakeholder relationships, and a third day to the multiple dimensions of organizational performance.

2. The management simulation realistically replicates the challenges in nonprofit management, requiring participants to make difficult decisions under pressure, lead and manage change, and work as a team. It enables them to try new behavior in a low-risk environment.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

3. Launched in August 2009, the evaluation study was funded by the New York Community Trust, one of the primary funders of Community Resource Exchange’s Leadership Caucus.

4. The study employed a three-part analysis: (1) it assessed the overall impact of the Leadership Caucus on individual leadership effectiveness and organizational performance;? (2) it isolated the relative impact of the various components of the caucus;? (3) it identified common themes, attributes, and differences among “low impact” and “high impact” caucus participants. High-impact participants demonstrated significant positive change as a result of caucus attendance. Low-impact participants are those for whom the caucus made little demonstrable positive change. Table 1 describes two high-impact cases.

The study used four outcome levels and three sources of data. The desired outcomes were categorized in order of difficulty to achieve:

Level one: Awareness and insights gained;

Level two: Desire for/confidence to change;

Level three: Changes in leadership practices;

Level four: Changes in organizational performance.

The three data sources were (1) personal leadership statements completed by participants at the end of the caucus; (2) postcaucus surveys, which CRE administered between one to four years after participants completed the program;? and (3) in-depth Interviews, which CRE conducted with high- and low-impact participants one to four years after completion of the program.

5. These observations are consistent with the literature, which posits that the totality of a learning experience makes a difference in outcomes.

6. The caucus includes an issue session for executive directors on partnering with a board. Participants reported on the session favorably. They now have greater awareness, desire, and ability to improve their own practices regarding their boards. On the other hand, they also say that they believe they can make only limited change in board governance. The broader issue is how the sector can bring best leadership practices to the board “theater.” To this end, CRE launched a board chair leadership caucus in November 2009.

7. These elements include a program of appropriate length and frequency, multiple learning methodologies working in synergy, feedback mechanisms, a focus on change initiatives, and a strong peer group of participants.

CRE’s High-Impact Success Stories

Alice* is the executive director of a grassroots advocacy organization in New York. The organization came into being after September 11, when a group of concerned immigrants decided to take a stand against discrimination and hate. Early roles in the organization were defined flexibly. Everyone pitched in, even the executive director and board members.

In 2006, at a turning point in the organization’s growth, Alice attended Community Resource Exchange’s Leadership Caucus. The organization had just moved from an organizing board to a governing board and handed over day-to-day program responsibility to Alice as the executive director. At this time of transition, Alice shared her concerns with peers about fully taking on the mantle of staff leader. Alice reports “feeling like a sponge for learning” during the caucus and being especially drawn to the content on managing change. She found the action learning sessions structured in small groups helpful. She left with specific guidance on her unique problems and the awareness that others had faced similar situations in their development as leaders.

As a result, Alice was able to counsel her board to give her the authority to do her job, which meant giving her a role in setting strategic direction, not merely being an executor of decisions. Alice attributes her ability to have the courageous conversation with her board to the coaching she received as part of her 360-degree evaluation and to the support of her peers. Alice has kept in touch with caucus colleagues and has even developed joint programming with one of them. The agency recently opened a second office on the West Coast and, over the next year, plans to establish a national advocacy presence, which is remarkable growth for a group that had only a local identity five years ago.

Joseph* is the founder of a group that provides urban youth with the skills and support to matriculate at selective colleges and competitive law schools. Although Joseph had been “in the business” for 20 years, when he took part in the caucus, he still saw himself as an emerging leader. He had never taken part in a formal leadership development program and didn’t know what to expect.

Joseph found the issue-based sessions particularly useful, especially when peers shared their experience of working with a board or their challenges in delegating to a senior team. Joseph used the caucus experience to implement two critical changes he had considered for some time: implementing a robust program evaluation as a key part of leading an organization to higher performance;? and coaching his management team to take on greater responsibility. “Our management team now functions well because I delegate more and hold them accountable more,” Joseph notes. “We lost a few staff who were barriers to the team’s effective functioning. But this has actually helped. I now feel very confident in the team’s ability to take over should something happen to me.” About the organization’s evaluation system, he says, “We’ve made both minor and major modifications to our programs based on what we’ve learned from our data. The evaluation system was nonexistent before the caucus. The need for it was sparked by what I picked up during that experience.”

* The names in this article have been changed.