In the spirit of Innovation: Many people believe that civility in American politics is at an all-time low. From shouts of, “You lie!” from the floor of the U.S. Congress, and the incessant torrent of partisan vitriol from talk radio and cable T.V., to senators from the left and right who reportedly don’t even speak to each other unless they have to, and a near government shutdown just weeks ago, it’s hard to argue otherwise.

So what can we do about it? Scientists (not political scientists) in Italy think they have come up with the answer.

Research conducted by Alessandro Pluchino and amici at the Universitá di Catania suggests that randomly selected legislators would make government more effective. Pluchino’s team won an Ig Noble Prize in 2010 for suggesting that random promotions of people in organizations actually increases organizational effectiveness and defeats the inexorable Peter Principle. This is the extension of the idea into politics.

The following blog post first appeared in the Physics arXiv blog on the website of the MIT-based Tech Review magazine. —The Editors

The democratic system of governance is one of the triumphs of civilisation. It ensures that our societies are run in the best interests of the majority. At least, that’s the theory.

In practice, there are numerous examples of democratic systems that are rife with corruption or paralysed by disagreement. Even in benign parliaments, it is often an open question as to whether the work they do really benefits the majority of people.

Today, Alessandro Pluchino and amici at the Universitá di Catania in Italy say there is a better way. They have modelled the behaviour of a two-party parliament and examined how it changes as randomly selected independent legislators are introduced into the system.

Their counterintuitive conclusion is that randomly selected legislators always improves the performance of parliament and that it is possible to determine the optimal number of independents at which a parliament works best.

They begin their analysis using a model of human behaviour first introduced by the economic historian Carlo Cipolla in 1976. Cipolla believed that the actions of every individual can be measured in terms of the benefits to themselves and the benefits to broader society.

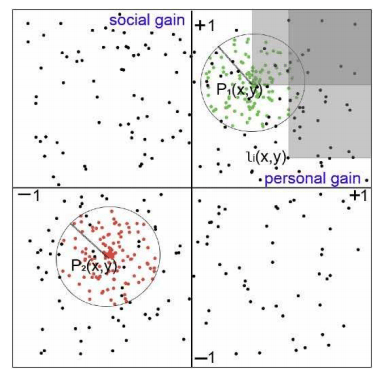

People then naturally fall into one of four categories, represented in the four quadrants of the diagram above. These categories are:

- Intelligent people whose actions produce a gain for both themselves and for other people. They lie in the top right quadrant;

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- Helpless/naive people in the top left quadrant whose actions produce a loss for themselves but a gain for others;

- Bandits whose actions produce a gain for themselves, but a loss for other people. They sit in the bottom right quadrant;

- Stupid people in the bottom left quadrant produce a loss for themselves and also for other people;

Pluchino and pals have used this classification to create an agent -based model of a parliament of 500 individuals made up of two parties. The members of a party all lie within a circle of certain size, centred at a point which represents their average behaviour. Independents can sit anywhere in the diagram and are introduced at random.

Each member of parliament can do two things: propose an act and vote for or against acts.

The question that Pluchino and co. investigate is how well the parliament performs as the number of independents increases. The measure of performance is the number of acts passed multiplied by their average social benefit.

They ran their model for various distributions of power in the two party system and found that in every case, adding random legislators improves the performance of parliament.

If Pluchino sounds familiar, it’s because we’ve talked about him and his pals before in relation to the Peter Principle, that incompetence always spreads through big organisations. Back in 2009, he and his buddies created a model that showed how promoting people at random always improves the efficiency of the organisation.

These guys went on to win a well-deserved IgNobel prize for this work.

So it’s not really a surprise that the same is true for other big organisations like parliaments.

Interestingly, random selection is not a new idea in democracies. For example, in the ancient Athenian democracy of the 6th century BC, drawing lots was the primary way of appointing officials.

Pluchino and co.’s result indicates that we would all be better off if we re-introduced this idea into modern democracies. As they put it: “We think that the introduction of random selection systems, rediscovering the wisdom of ancient democracies, would be broadly bene?cial for modern institutions.”

Has there ever been a double winner of an IgNobel?