This article was first published online on September 21, 2005.

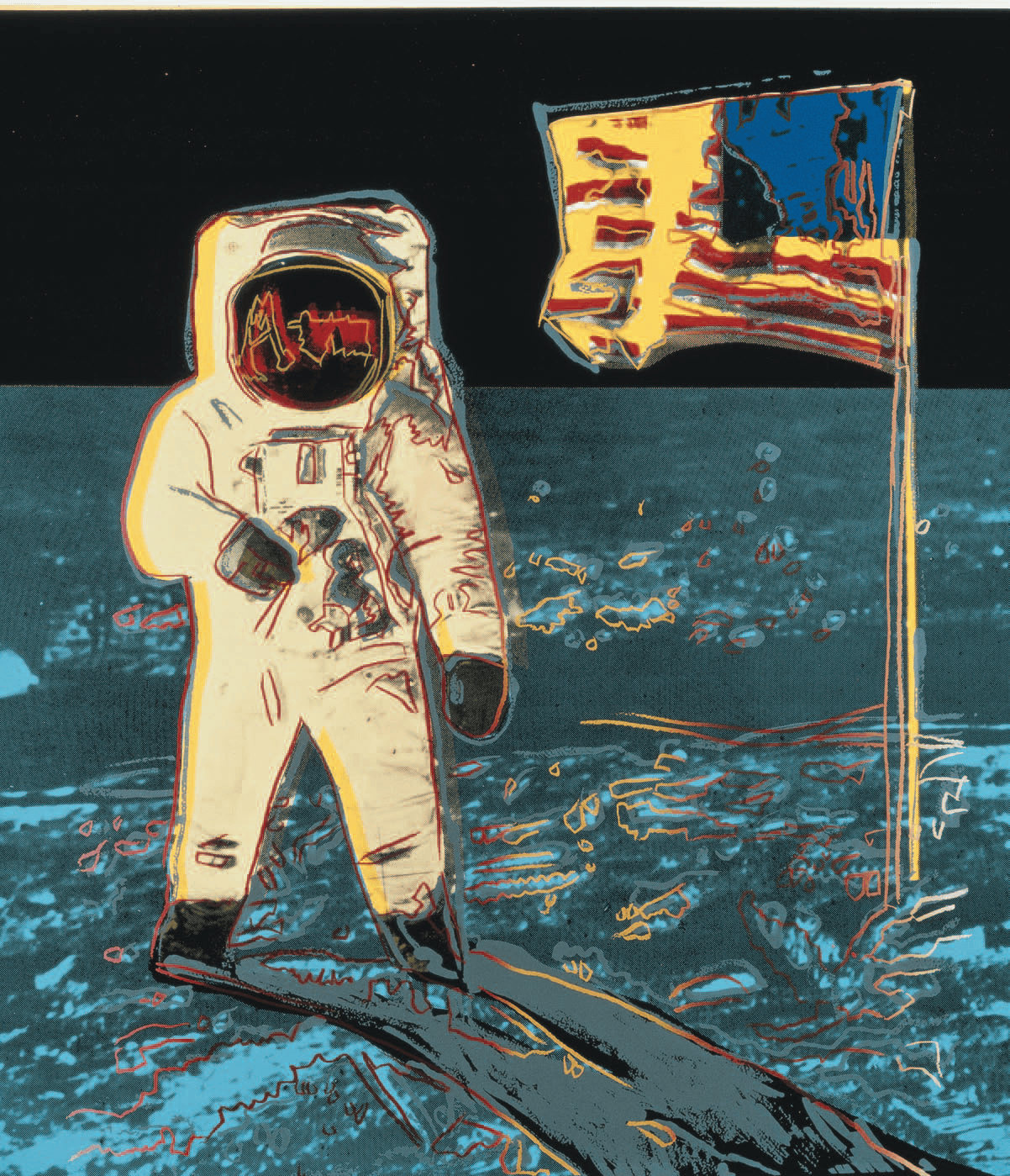

“We will put a man on the moon by the end of the decade.” This declaration by President Kennedy is considered one of the most effective national promises ever made. Not because we were fascinated by the moon, or space, or even science, but because it allowed us, as a nation, to lift our eyes to the heavens and dream. It gave us an aim. More important, it created a sense of pride by getting us to hold our heads up high—and to recognize the possibility that resided in our country’s best efforts.

The most important word in President Kennedy’s statement is the first one: “We.” The moon immediately became a shared goal that could only be achieved through an effort in which everyone participated. Only one or two of us might actually get to set foot on the moon, but it would take all of us to get them there. The passion of achieving that dream may not have been visible in our daily activities, but it was more than evident as the country huddled together around the television that hot summer day to watch the astronauts fulfill their promise.

Similarly, an effective organizational promise is identified through an honest assessment of ability, opportunity, and desire. Tapping the collective aspirations of board, staff, and community partners can inspire a bond, motivating the whole to expand their thinking beyond the routine of their individual roles and recognize the exciting places their shared effort can take them. With such compelling internal clarity, a nonprofit’s organizational promise can have a profound impact on how value is delivered and communicated. The promise elevates the organization’s brand identity by giving context to the relationship it is building with participants and supporters.

More than 10 years ago, County Memorial, a full-service, acute care hospital serving eastern Montana, changed its name to the Sidney Health Center. This re-branding effort brought the hospital, extended care, and assisted living facilities together under one moniker to offer the region a continuum of health services. What it failed to do, however, was change the relationship between the institution and those it served. A new logo and promotional campaign had little effect on a growing community perception that the organization, though essential to the region, was “a large, impersonal corporation.” There was a distinct disconnect between what the organization communicated to their participants and supporters and what it actually delivered. These perceptions, spread from person to person through casual conversations between families, friends, and neighbors, formulated a brand identity that superseded any marketing and communication campaign. This identity had become so dominant that it overshadowed many of Sidney Health Center’s strengths and achievements; it also became rooted in the hospital staff’s perception of their employer.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Identifying the factors that create negative perceptions is like unraveling a huge, knotted ball of string. The bottom line is that a negative brand identity often reflects a break in an organization’s connection to its mission and the principles that guide its behavior. This lack of internal clarity threatens the fundamental health of the nonprofit—as a result, the institution offers less and less relevant value to participants and supporters. Making a promise builds a deep understanding among board and staff about the kind of value they should create and how it should be delivered. The main outcome of this work is an organization empowered to guide perception by producing results that are meaningful to the community it serves. Communication and fundraising efforts are then able to tie into a deeper theme as well as strengthen the organization’s relationship with stakeholders by highlighting actions that speak louder than words.

Tips for Creating a Promise

- Keep Participants and Supporters in Mind: First and foremost, your promise has to be deeply meaningful to them.

- Collaborate! Effective promises grow from diverse points of view.

- Make It Compelling: Think beyond the next three years; consider what can be delivered and achieved over the next ten years.

- Consider Your Capabilities: Don’t limit yourself to what you currently know or the resources you currently possess; recognize and plan to build on your strengths to expand what you know and possess.

- Test It! Share your promise. If someone thinks it is impossible, you are probably on the right track.

Last year, the board and staff of the Sidney Health Center made a promise to deliver to the citizens of eastern Montana “exceptional personalized care.” Recognizing that the hospital’s staff is the most important touch point for patients and visitors, initial actions focused on small, yet significant, shifts in operating practices. Employees from across the hospital formed the LIFE Team, which has addressed customer service issues through an innovative service reward program. The human resources department revised their methods for creating job descriptions and evaluating employees by clearly stating customer service expectations. The finance department made changes to its billing and collection practices to create a department that can meet the needs of each individual patient. Future plans include helping patients clearly understand the costs associated with services before they commit to them, the establishment of a patient advocate initiative to guide patients through the process from admittance to after-care, and finally, an upgrade of the physical plant and technology to create a more welcoming and friendly environment.

In a short time, this shift in operations has created a sense of urgency and ownership in the human resources department to deliver and achieve the organization’s promise. As it has been adopted, the promise has begun to manifest itself in impromptu daily interactions. For example, the radiology staff redecorated the room where mammograms are performed to create a warmer, less sterile environment, and the CEO shares responsibility with other senior staff to visit in-patients every day, delivering a newspaper and checking in to see how they are doing.

Their brand identity is beginning to shift as well. Hospital staff are reporting a greater sense of optimism among fellow employees in regard to their employer. Community members are also recognizing the benefits of the promise; this has been ensured by a marketing and communications department that is now empowered to guide patient and visitor perception.

When creating an effective organizational promise, a nonprofit should consider conducting a full assessment of its current brand environment. This is done by tracing the link between participant/supporter perception and the results generated by the organization; how results relate to board and staff capabilities; and finally, how board and staff capabilities frame a promise to take action based on the organization’s mission and values. By recognizing how perceptions are formed and how they connect to the organization’s mission and values, leadership is able to gain insight into how it needs to reposition its relationship with participants and supporters in order to strengthen the perceived value of their work. Formulating or clarifying a promise provides significant leverage in accomplishing this.

The moon may not be the desired destination for every organization, but there is tremendous value in declaring, as a group, what the “moon” represents. Through every step we took to get to the moon, the promise became less about the president who made it and more about both the people who strove to achieve it and the country it impacted. Acknowledging with one another the promise of what is possible creates a shared goal and gives value to each individual’s skills, resources, and efforts.