“Recognize that diversity brings richness. Diversity brings new ideas. Diversity brings growth. Diversity brings dynamism. Diversity brings energy. And lack of diversity means sameness, dullness, lack of growth.”

—Interviewed board member

Diversity abounds in our communities and organizations, and our understanding of what constitutes diversity continues to grow as patterns of difference shift, yet in many cases we, and our organizations, struggle to keep pace with societal trends. While diversity has many aspects, including individual differences along dimensions such as education or training, personality or style, this article focuses primarily on diversity based on dimensions such as culture, ethnicity, race, age, sexual orientation, and gender. We are looking at a particular context in which such diversity is a concern for many nonprofits, and that context is the boardroom.

The Urban Institute’s Francie Ostrower noted in a national survey of nonprofit governance in the United States that 86 percent of board members are white (non-Latino);? a mere 7 percent are African American or black;? and 3.5 percent are Latino. In a survey of nonprofit boards from across Canada, conducted in 2008, we found that the majority of board members were between 30 and 60 years old, and 44 percent were women. Almost 28 percent of the organizations indicated that there was at least one person with a disability on their board, while 22.4 percent of those surveyed had a board member who was openly lesbian, gay, or bisexual. Only 13 percent of board members were what in Canada are termed “visible minorities,” or persons of color.

While funders and others often seem to be advocating for more representative diversity on boards, this has not yet resulted in large shifts in board composition, with the exception of women. It is likely that you have heard the arguments in favor of increasing board diversity, including the claim that more diversity leads to superior financial performance, better strategic decision making, increased responsiveness to community and client stakeholders, and an enhanced ability to attract and retain top talent. But you may also have heard that researchers have found a correlation between increasing diversity among governing groups and greater conflict, as well as a deterioration in performance.

We too have struggled with these mixed messages. We wanted to deepen the conversation about diversity on boards through empirical research, in order to better understand the roots of this paradox and what is being done to respond to demands for both increased diversity and effectiveness.

We began by talking to eighteen board members from the voluntary sector in Canada who are viewed by their peers to be leaders in the effort to diversify boards. We were interested in looking at how they made sense of diversity, and what they saw as the best practices for enhancing it. While academics have tended to focus on diversity and the dynamics of “exclusion,” communities of practice are now talking about “inclusion.” Our informants described inclusion as an alternative to assimilation, in which all people are treated the same, or differentiation, where differences are celebrated and leveraged with the potential consequences of tokenism and exclusion.

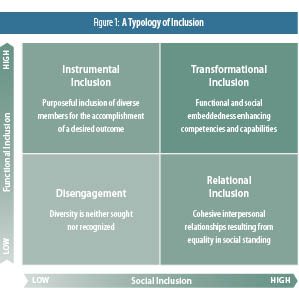

We came to define board-level inclusion as the degree to which members of diverse and traditionally marginalized communities are present on boards and meaningfully engaged in the governance of their organizations. We also noted that our informants implied that at times inclusion had potential transformational impacts for both traditionally marginalized individuals and for the board itself. Kristina A. Bourne similarly describes an inclusion breakthrough as “a powerful transformation of an organization’s culture to one in which every individual is valued as a vital component of the organization’s success and competitive advantage.” Bourne describes this concept as an alternative to seeing diversity as an end in itself or something to be managed or tolerated. But her claims, and those of our informants, have not yet been empirically examined. Reflecting on our interviews, it seemed that our informants were talking about two different types of inclusion—which we came to call “functional inclusion” and “social inclusion”—and about how the two can work together to create something transformational.

Functional inclusion emerged from our research as characterized by goal-driven and purposeful strategies for the increased inclusion of members of diverse or traditionally marginalized communities. Social inclusion, in contrast, is best characterized by the participation of members of diverse groups in the interpersonal dynamics and cultural fabric of the board, based on meaningful relational connections. Unlike the functional notions of inclusion, social inclusion also stresses the value derived from social standing and relational acceptance within the context of the board. Reflected in this view of relational acceptance is the need for members of traditionally marginalized communities to be authentically engaged as whole members of the board, avoiding marginalization and alienation.

We concluded that people were basing their comments on an implicit model, and we are suggesting that the combination of both types of inclusion could transform governance and create what we have come to call “transformational inclusion” (see Figure 1).

As Figure 1 proposes, the board that focuses exclusively on functional inclusion and on taking a “making the business case for diversity” approach will end up with what we are calling “instrumental inclusion.” Similarly, boards that focus exclusively on social inclusion end up with what we are calling “relational inclusion,” a model that tends to make people “feel” good. Boards that do both instrumental and relational inclusion, however, can generate transformational inclusion. To be really successful, boards of directors need to empower members using functional processes, and they must do so while integrating (rather than assimilating) diverse members using social and relational means as well. For these reasons, we hypothesized that governing groups which are more diverse, and which implement functionally and socially inclusive practices, will be more effective and have higher cohesion and greater commitment than their less diverse counterparts.

We decided that this hypothesis deserved to be tested, and developed a questionnaire that surveyed respondents from 234 boards of directors operating in Canada’s nonprofit sector. We measured board diversity by counting the number of ethnocultural and visibly different groups represented on the boards. Our analysis of the impact of increased diversity on boards supports previous research documenting the challenges of diversity. We found that higher levels of diversity were correlated with perceptions on the part of our respondents of lower levels of board effectiveness.

Previous research similarly indicated that diversity leads to conflict and lower performance levels. Fortunately, this is not the end of the story, but it does tell us that it is not enough for boards to simply add members from diverse communities and expect positive outcomes to result. Unless meaningful steps are taken to include members in the functional and social aspects of board life, increasing diversity tends to result in perceptions of greater conflict and dissatisfaction with board performance.

Our study showed that meaningfully engaging diverse members in the social and functional aspects of board work attenuates, and in many cases mitigates, the perceived performance deterioration that occurs when diversity is increased along the lines of the functional or social model alone. This is an important finding, as it offers evidence that diverse governing groups need not sacrifice board performance for the sake of increased diversity. Indeed, functional inclusion was found to be positively associated with overall board effectiveness, cohesion, and commitment, while it did little for group cohesion and commitment. Social inclusion, on the other hand, had little direct impact on board effectiveness, but added significantly to group cohesion and commitment. There is a need to balance both social and functional inclusion, lest boards neglect one dimension (social inclusion) in favor of focusing prominently on the other (functional inclusion).

The cumulative implications of diversity and inclusion are complex and intertwined, but largely support our general theme that functional and social inclusion enhance the effectiveness and viability of governing groups, particularly in relation to making the more diverse groups effective, cohesive, and committed. The (direct and indirect) patterns of relationships that we found between board diversity and board effectiveness speak to the transformative potential that lies at the heart of inclusion.

Given these findings, what can boards that want to benefit from diversity actually do in order to create more inclusive governing bodies? In the following sections we describe steps that people we interviewed think are useful in building functional and social inclusion. These are steps that are being enacted by boards as a whole as well as by individual board members who care deeply about inclusion.

We have characterized functional inclusion as goal driven and committed to purposeful strategies for the increased inclusion of individuals who identify as coming from diverse or traditionally marginalized communities. In the interviews, individuals who saw themselves as champions of change described many actions that they had personally taken to make their boards more inclusive, working to get on the board and into positions of influence—such as on governance, diversity, or executive committees—for example, and then pushing for more inclusion of others.

These individuals expressed discomfort at rocking the boat and disrupting the status quo, but they did so intentionally. Some saw how this type of action could lead to tokenism, where a person is added to the board primarily because of his or her difference, or based on quotas or agendas. This opens the door to such questions as, “What do women think about this?” being asked of the only—or token—woman on a board, based on the faulty assumption that one person can speak for a whole demographic community. But the informants also said things like: “If you get the right person, that person can start advocating and then do something. Sometimes tokenism backfires on the people who try to use it.” Having a seat at the table presented diverse board members with an opportunity to advance diversity interests and agendas. One person, for example, said:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Before I came on the executive board, what was happening at the board meeting was the executive would decide what things should come to the board, and present them to the board, and the board [always] said yes. The chair thought that I would be a nice person to be appointed to the board, especially because I come from a diverse community. After about the third executive meeting, of course, she said, “I am very disappointed in you because, you know, we want executive solidarity.” So I said, “You’ll never get that as long as I’m on the executive board, you can be sure—because I came on the board to represent certain views, and you will hear about those things.

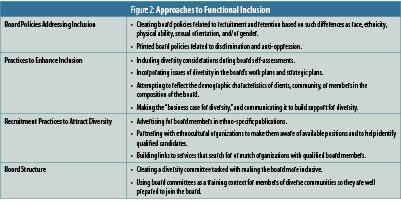

Functional inclusion at the level of the board involves steps taken by the board as a whole to increase representation of members of diverse communities through its policies, structures, practices, and processes. One characteristic of this approach is to focus on stakeholders and make what we often heard called “the business case for diversity.” The business case involves assessing the benefits of diversity, and can include considerations such as creating greater access and legitimacy for different constituents, helping the board appear forward thinking, attracting resources, and to a greater extent representing the interests of the communities being served by the organization. The functional approach to inclusion was frequently characterized by a conscious investigation of the demographics of the agency’s stakeholders, such as clients, members, or communities served. This would be followed by a “mapping” of that pattern of diversity onto the board to see if the external diversity was represented there. One nonprofit hospital described it this way:

We looked around the board and saw that we had women covered because half the board members were female. But we wanted to be more reflective of the community, so we did a survey of the patients in the hospital. To be proportionate to the patient population, we realized that the board should add at least one culturally Italian and one culturally Cantonese Chinese board member.

Respondents provided examples of strategies for purposeful inclusion ranging from the general (“Gender diversity was very consciously planned to make sure to maintain a balance”) to the scientific (“We had overall a good ratio of different ethnic backgrounds”), and, finally, the tactical (“We tried to think of women that we were working with in the community who were from more marginalized communities or traditionally marginalized communities, and decided to target them. We’re doing purposeful recruitment, and I think that has really made a difference”). One particularly salient reason for attempting to include marginalized community members in the board structure is based on the expectations of powerful funding bodies;? as one respondent succinctly stated, “The boards will wake up if the funders ask for it.”

Although these strategies differ, they share an approach to including diversity within the existing framework of the board via functional approaches such as changing formal structures, processes, and policies. (See Figure 2, below, for other strategies we heard boards using to increase diversity.)

Social inclusion is characterized by the participation of members of diverse groups in the interpersonal dynamics and cultural fabric of the board based on meaningful relational connections. Statements such as, “For me, diversity .?.?. it’s definitely a sense of inclusivity of everyone and everything. I think that [it incorporates] inclusivity, respect. I think respect for different people’s beliefs and values is critical,” demonstrate an awareness of inclusion as existing beyond task or functional views. Respondents who spoke of overcoming feelings of alienation, made comments like, “I was feeling very uncomfortable, but after some time, of course, I had to assert myself, and I had the support of [a member of high social standing], so it was okay.” Similarly, another person we interviewed spoke of the process of gaining inclusion, claiming, “I think I persevered, and really enjoy the experience now, and the group is just very receptive to everyone’s ideas, and we all encourage one another.”

Although the process of becoming included in social aspects of the board may not be automatic, it is an essential facet of genuine member integration. Individuals from traditionally marginalized communities we talked to spoke about how they used humor to help overcome tension, how they worked to build relationships, and how they were conscious of the need to build trust within the board.

Our informants also reflected on board-driven efforts to improve social inclusion that included mentorship and coaching, orientation practices, and other group-building processes such as retreats and workshops. These initiatives illustrated the belief that strong social relationships and higher levels of trust and respect are crucial to improving decision making and information sharing. For example, one board used mentors, and we heard the following statement: “We actually assign a board member to mentor new members, particularly young people. And that involves making a personal connection with them, phoning them to remind them about meetings, following up with them after meetings to see how they felt about how the meeting went.”

Other strategies for building social inclusion included holding meetings at times and in locations where everyone could attend (in locations with elevators in order to be accessible to those with physical disabilities, or on days that accommodated religious holidays, for example), as well as providing such services as signing for the deaf or hard of hearing. Similarly, some boards made sure that any food that was served accommodated the dietary restrictions and cultural preferences of different members. There was sensitivity, too, regarding the use of humor and choices of subject matter (such as conversations about sports teams or summer cottages) that could marginalize or silence people, or exhibit unconscious privilege.

Thus, social inclusion at the board level centered on building connections and awareness with the intention to create a positive and inclusive board culture. Informants acknowledged the importance of using formal initiatives to create relational bonds that contribute to the performance of the board: “We did talk about the need for coaching people and partnering people, and giving people a friend on the board to provide extra support and translation. It’s like cultural translation for any new member, but particularly for new members who either don’t have a lot of experience or don’t know there’s a dominant culture at the board that is different from where they might be coming from.” The energy spent building relationships to foster a shared understanding was considered by many to be important in attracting and maintaining an active membership within a more diverse board. A strong and welcoming organizational culture was depicted as another way of increasing feelings of inclusion, which reduced detachment and turnover.

Our results suggest that if you want to have diverse governing groups, you need to find a way to genuinely speak to people from marginalized communities, support these members through the transitional phases of board entry, and authentically engage them in social aspects that build strong relationships and board cohesion. One of the core findings of our investigation suggests that underlying social inclusion is the authentic understanding that social relationships have value in and of themselves beyond any value they may have as a way to accomplish functional ends.

As described above, during our interviews we heard people talking about social inclusion and functional inclusion, but there seemed to be another, even more important message embedded in the conversations: When it comes to issues of diversity, all too often the relationship between traditionally marginalized individuals and the boardroom can be compared metaphorically to an egg used in the baking of a cake, as seen through the eyes of a child. We like this metaphor and ask you to visualize a child helping his or her father make a cake, first by mixing the dry ingredients together, and then removing an egg from the carton and placing it whole into the bowl and starting to stir. The father laughingly points out that the egg must be broken and the mixture transformed before the cake is ready for the oven.

Traditional views of diversity stress the benefits attributable to representation—like the unbroken egg placed carefully into the bowl. Missing from those perspectives is a discourse recognizing the transformative implications of mixing the egg into the otherwise dry batter, where both are irrevocably changed and it becomes impossible to separate out the various ingredients into their original forms. Also missing is the recognition that just as the cake batter is impacted by the heat in the oven, so are the changing expectations of funders, members, clients, and the public at large, who are turning up the heat on nonprofit boards and demanding that they be more representative of their communities. This article develops a theory of transformational inclusivity as a reconciliation of the dilemmas faced by individuals and organizations struggling with the challenges of workgroup diversity, which if not embraced from an inclusion perspective can actually lower the effectiveness of a board.

Returning to our cake baking metaphor, it is clear that neither eggs nor cake-mix alone are enough to create a cake. Both are necessary, but neither one is sufficient on its own. A similar assertion has been argued throughout the course of this article, based on our belief that neither functional nor social approaches to inclusion are independently sufficient for a board of directors to be truly inclusive in its orientation. Boards need to consider diversity as inclusivity that influences the board in its entirety—not only with respect to transforming composition but also in terms of transforming culture and structural parameters.

Inclusivity is a culture-changing process, and one that will bring a multitude of divergent logics and ideologies to bear on shared and sometimes divergent interests. Rather than construing this effort as simply providing a new seat at the table, genuine transformational inclusivity will result in a distinctly changed entity—one that balances permeable and responsive boundaries with achievement-oriented focus intended to meet the demands of the board and its mission.

, is a professor at the Schulich School of Business at York University in Toronto, Canada.

, is an assistant professor at the Sprott School of Business at Carleton University in Ontario, Canada.