“THE EARTH SCRATCHES HERSELF” BY NATHALIE VIN / WWW.MOSAICWORLDS.COM

Editors’ note: This article is featured in NPQ‘s blockbuster summer 2013 edition: “New Gatekeepers of Philanthropy.”

Why do donor-advised funds (DAFs), as an instrument of charitable or philanthropic giving, so often seem to stir up a hornet’s nest of commentary and complaints? One would think that as the conveyer belts moving billions of dollars from charitable donors to charitable recipients, accomplished with a few cursor movements and a click, DAFs would be widely applauded for making charitable giving easier, faster, simpler.

In years past, criticism focused on the role of large financial institutions, such as Fidelity Investments, Vanguard, and Charles Schwab, among others, serving as the sponsors and managers of donor-advised funds. Being corporate players, their role in the donor-advised fund field was viewed—largely by their competitors in community foundations—as suspect. The fact that these corporate sponsors were earning little to nothing from their 501(c)(3) national DAF arms, that community foundations were themselves often tied quite closely to local banks and other corporations, and that the corporate DAFs were operating more cheaply and flexibly for smaller donors than community foundations, however, has worn down the theory of corporate taint. Now, the criticism leveled at DAFs is spotlighting not their corporate roots but rather their grantmaking practices.

Think of the managers of DAFs—whether the couple of dozen corporations in the game, the 750 community foundations (as of 2011) whose giving is largely dependent on the DAFs they control,1 or the many other institutions (universities, hospitals, and other independent charities) that hold and manage DAFs—as gatekeepers to a large and rapidly increasing swath of philanthropy. DAFs already dominate the resources for giving by community foundations, and small private foundations are discovering that it is simpler and cheaper to operate as a DAF—with the likes of Fidelity Investments and Charles Schwab providing the institutional operating infrastructure—than to straggle along as a small grantmaker. Despite the popularity and growth of the national DAFs, critics continue to raise issues about the accountability of donor-advised funds.

The critics aren’t fly-by-night naysayers but rather well-respected observers of the philanthropic scene. Boston College law professor Ray Madoff calls DAFs “problematic because they are based on deception.” In comments submitted to the Internal Revenue Service, Madoff wrote, “The legal regime governing DAFs undermines the integrity of the tax system by implicating the government in a ‘wink and a nod’ system that encourages artifice over substance.” 2 In Madoff’s conception, the concern is that donors make irrevocable (fully charitably deductible) gifts to the 501(c)(3) sponsors, who then hold and administer the funds, “leav[ing] donors vulnerable to unscrupulous and insolvent sponsoring organizations that choose to exert their legal rights over the funds rather than their ‘understanding’ with the donor.” 3

One element of the “wink and nod,” as seen by the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy’s Kevin Laskowski, is the dynamic of DAF distributions, or “payout.” Laskowski notes, for example, that, in the aggregate, 126 large DAF managers had a payout rate of 22 percent of their $24.2 billion in assets; but a 2006 Department of Treasury study of more than 106,000 individual DAFs demonstrated that, while showing a mean payout of 9.3 percent, the DAFs had a median payout of 0.6 percent, half of the DAFs had a payout of less than 1 percent, and one-fourth had no payout at all during the study year.4

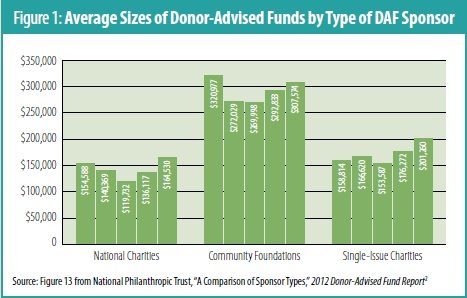

Are DAFs a “wink and a nod” for potential donors? Although the typical account size for a DAF at a community foundation is quite large (often five or six figures and, for some of the commercial sponsors, requiring a minimum investment of at least $25,000), increasingly DAFs are a charitable donation instrument for middle-income investors with the impulse to give—and many, such as the investor in the story below, are more and more finding DAFs an attractive vehicle for doing so.

The Middle-Income Donor

A few years ago, a DAF investor (who prefers to remain anonymous) and his wife had an equity investment, made up of mutual funds, with Fidelity Investments.5 The investment had appreciated greatly, but the couple were informed by their financial advisor that at that time it had “gone as far as it was going to go.” It wasn’t a large investment—worth perhaps $17,000 if it were sold—and the capital gains hit would have been significant.

The Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund had lowered its minimum threshold for establishing a donor-advised fund, from $10,000 to $5,000 (subsequently matched by Schwab Charitable), and the couple were advised that if they donated the stock rather than selling it, they would avoid the capital gains hit. Because it was a Fidelity account, it was easy for them to transfer it to the gift fund. It was basically conducted online. As they put it, they “did it in about three or four clicks.” The administrative cost? Fifty to sixty basis points, as they recall.6

The online ease in establishing the fund was matched by that of using it for making donations. For the couple, it was “our philanthropic checkbook.” They used it to make donations “very much tied to things that we’re committed to,” including, in their case, a foundation that supported their local public library and another foundation that raised money for their public school. After four years, they had spent down their small DAF, but they decided to add additional funding to it. Interestingly, they pointed out that for them the attractiveness of a DAF was that, as moderately sized investors and charitable donors, they didn’t need to pay for charitable advice. In their view, “ultra-high-net-worth individuals or families [as a result of] an IPO, or, most importantly, when a family business is sold, [when] there are some serious assets moving, these are the folks who are looking for new situations, looking for charitable advice.” Those high-net-worth individuals might set up a DAF with a sponsor that caters to givers of a couple of million a year, but for middle-income givers, paying another fifty to one hundred basis points is a premium that, as small donors, they neither want nor need to pay.

A recently retired community foundation CEO confirmed the couple’s DAF experience, explaining that “the typical Fidelity donor is using it more like a charitable checking account. People basically know where they want to give, and need a mechanism to do it. They don’t see the added value of advice from a foundation.” But they aren’t quite the same as a checkbook. Linked to the donors’ array of other financial assets—with charitable investments and income investments presented through an integrated online platform—DAFs are rather more contemplative and research oriented than your typical checkbook. On most DAF platforms, a donor can see his or her entire history of grantmaking, generate an analysis of the kinds of organizations supported, and move more money into DAFs from investments.

DAF Assets Skyrocket

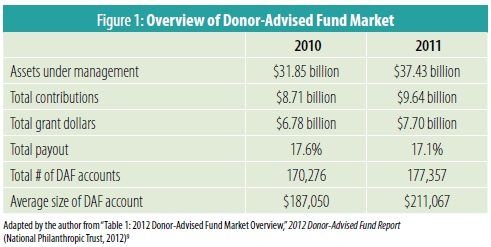

Our donor couple in question are hardly alone in finding DAFs an increasingly attractive vehicle for charitable giving. As figures 1–3 (see below) demonstrate, donor-advised funds are a significant and growing part of charity and philanthropy. As of 2011, the National Philanthropic Trust tracked 652 DAF sponsors—including commercial funds and community foundations—managing a combined total of 177,357 DAF accounts, finding that they had, in aggregate, $37.43 billion in assets under management, received $9.64 billion in contributions, and distributed $7.7 billion in grant dollars for a total payout (grant dollars divided by assets under management and grant dollars) of 17.1 percent.7

Although DAF assets declined during the deepest part of the recent recession, they skyrocketed in 2010 and 2011, increasing by $10 billion in asset value over 2009. And, while the rate of DAF grant or payout growth wasn’t quite as high as the growth in assets under management, they still increased from $6.26 billion in 2009 to $7.7 billion in 2011.8

On a cumulative basis, all DAFs add up to one massive foundation, with $37.43 billion in assets—slightly larger than the one largest individual foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which in 2011 had assets of $34.6 billion. In comparison with the cumulative DAF grants payout of 17.1 percent, the Gates Foundation qualifying distributions (including permitted administrative costs) that year reached 11.44 percent, and its grants-only payout was 9.34 percent. For the top forty-nine foundations (including five community foundations) that reported assets under management, grants payout, and total payout, their cumulative grants payout was only 5.34 percent, and their total qualifying distributions, including PRIs (program-related investments), loans, and permitted administrative costs, were 6.37 percent. Removing the high-payout Gates Foundation from the list, the cumulative grants payout of the remaining forty-eight largest foundations drops to only 4.47 percent and their cumulative total distributions to 5.27 percent.10

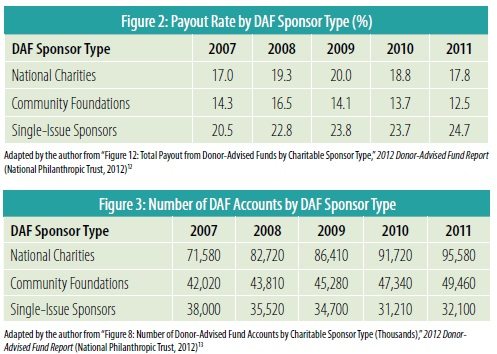

Nonetheless, as Laskowski points out, that 17.1 percent is a cumulative payout for all DAFs.11 By type of sponsor, single-issue DAFs had the highest cumulative payout rates and community foundations the lowest, but all were decidedly higher than the typical private foundation payout rate, which hovers around 5 percent (see figure 2, below).

However, unlike institutional foundations whose 5 percent payout rates, for example, apply to their entire assets annually, a national sponsor’s or a community foundation’s donor-advised fund payout rate applies to the funds of dozens, hundreds, or in some cases thousands of donors, and, as a result, several DAFs with high payout rates could camouflage a DAF that pays out little or nothing over the years (see figure 3).

The challenge would be to determine the individual payout rates of individual DAFs and develop a median of the payout rates of tens of thousands of accounts. The commercial DAF sponsors, for one, report that, while operating as public charities and therefore not subject to a private-foundation-qualified distributions requirement, they encourage their donor-investors to maintain a reasonable payout rate and set up triggers if some accounts appear to be sitting on their assets.

Contributions to the big three national DAF sponsors—Schwab, Fidelity, and Vanguard—were up 44 percent in 2012 compared to the previous year, according to Schwab Charitable’s president and CEO, Kim Laughton.14 In the fourth quarter alone, compared to a year before, charitable contributions tripled and new accounts doubled. According to Sarah Libbey at Fidelity, 2012 was a record year at the biggest of the national sponsors—$3.6 billion in incoming contributions, processing $1.6 billion in 428,000 grants to charities.15 As Laughton noted, “a good chunk” of the increased 2012 activity was related to the fiscal cliff, as donors feared that Congress would reduce the excluded amount on estates for estate tax purposes and increase the capital gains rate.16 The potential change in the estate tax—which didn’t occur, when all was said and done—brought some donors into talking to financial planners and charitable advisors, conversations in which charitable giving undoubtedly arose as a discussion topic in light of the potential tax structure uncertainties. To Laughton, the interesting dynamic is that the 2012 pace of setting up DAFs, at least in her experience at Schwab, didn’t slow down in the first quarter of 2013, even though the fiscal cliff had, for the moment, been settled.

The DAF Payout Issue: What Is Really Going On?

Responding to the assertions of critics that the high payouts of DAF managers camouflage the low or no payouts of some specific funds, Libbey noted that Fidelity Charitable “has a formal policy that is stated in our circular about minimum grant activity, but we [also] make sure that we are tracking donors and callout campaigns [so] that if we see an inactive donor they’re made aware of that status.”17 The specific language of the Fidelity minimum activity guidelines is as follows:18

Minimum Grant Activity

Historically, Fidelity Charitable has made grants of more than 20% of average net total assets to charities each year. The formal grantmaking policy requires that minimum annual grants, on an overall basis, be greater than 5% of average net assets on a fiscal five-year rolling basis. If this requirement is not met in a fiscal year, Fidelity Charitable will ask for grant recommendations from Giving Accounts that have not had grant activity of at least 5% of the Giving Account’s average net assets over the same five-year period. If Account Holders on these Giving Accounts do not make grant recommendations within 60 days, Fidelity Charitable will transfer the required amounts to the Trustees’ Philanthropy Fund (described on page 28), from which the Trustees will make grants at their sole discretion.

Minimum Giving Account Activity

If a Giving Account is dormant for seven years (i.e., total grants distributed over that period are less than $250 with respect to a Giving Account), Fidelity Charitable will make every effort to contact the Account Holder to encourage him or her to satisfy this requirement by recommending that one or more grants be made totaling at least $250. If the Account Holder does not respond by recommending at least $250 in grants that are distributed from the Giving Account within a reasonable time, Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund will transfer the entire balance of the Giving Account to the Trustees’ Philanthropy Fund.

The Trustees’ Philanthropy Fund (TPF) is the Fidelity entity that receives control of DAF account assets when, for example, a donor dies and leaves no successor. Between 1991 and 2012, over two decades, the TPF made $13.4 million in grants; in 2012, the $1.5 million in TPF grants were mostly for disaster relief (40 percent), with the remaining going to charities involved in food banks and food distribution (25 percent), supporting children and families (21 percent), and supporting the philanthropic sector (14 percent). Only $1.7 million was granted out in 2011.19 That isn’t much money in the TPF, suggesting that Fidelity doesn’t find itself absorbing too many dormant accounts that merit their transfer to the trustees, and the evidence needed to show something other than dormancy—$250—isn’t an aggressive level of giving.

Remember that a donor who establishes a donor-advised fund at Fidelity, Schwab, or a local community foundation is making an irrevocable grant to the entity, receiving immediate charitable deduction tax benefits, but in theory is only able to recommend to Fidelity, Schwab, or that charitable foundation the grants that would be made from the account. However, as a Congressional Research Service (CRS) report from last year noted, “in practice [the donors] determine when and how the funds are distributed because sponsoring organizations typically follow their advice.”20 In other words, unless the donor wants to make a grant to an organization that isn’t a qualified public charity or wants to do something otherwise untoward with the funds, the DAF sponsor is going to follow the DAF donor’s “recommendations”—or else the donor will be looking for other account managers.

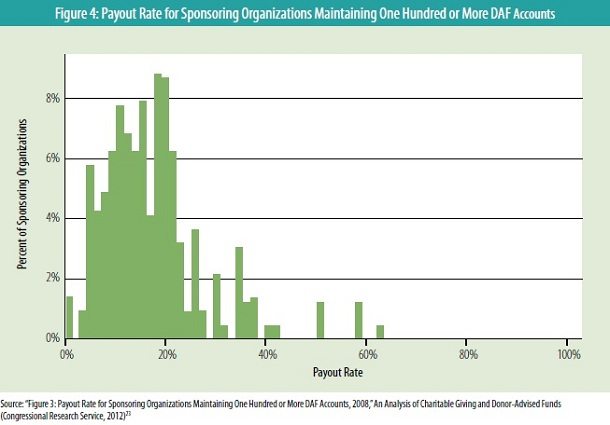

A 2011 Treasury Department study of over 180,000 donor-advised funds revealed that for DAF sponsors with only one or a very small number of DAFs, there was a significant program of payouts per account, presumably following the donors’ directives. More than half of the DAFs in single-account DAF managers showed no payout in 2008 and that 70 percent had payouts lower than 5 percent. However, 87 percent of DAFs are held and managed by entities with one hundred or more accounts, and their payouts are much higher (see figure 4, below).21

The large commercial funds and community foundations may be the most recognizable DAF sponsors, but they do not seem to be the ones that are laggard in their distributions. In the Treasury study described by the CRS report, 453 out of 1,828 DAF sponsoring organizations did not pay out any grants at all in 2008. Of the 453 no-payout sponsors, 334 managed only one or a very tiny number of DAFs. The payout rates, for the more typical DAF sponsors that managed one hundred or more accounts and for the commercial funds, were much higher. Eighty-seven percent of all DAF accounts are managed by sponsors with one hundred or more accounts, but only 3.6 percent of those individual DAF accounts showed a payout rate of less than 5 percent.22

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Do the big sponsors such as the commercials or the community foundations want the DAFs simply to sit so that they can earn management fees, or do they want the moneys to flow into accounts and out to charities? Most financial advisors seem to believe in active capital investment strategies, rarely content with simply letting moneys sit. Libbey described the DAF management strategy, at least in her shop, as “financial services acumen applied to a planned giving vehicle.” It would seem that the bigger managers—with multiple accounts—have an interest in getting moneys to flow, while the smaller sponsors may have something else in mind. While controlling a substantial portion of DAF assets, the commercial sponsors in the Treasury analysis represented only 31 out of the total of 1,828 DAF sponsoring organizations.

The critics of DAF payout rates cannot suggest that they are sanguine about foundation—much less private foundation—payout rates. If, in addition to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the five generally higher-payout community foundations in the list of the nation’s forty-nine largest foundations are pulled out of the analysis, their cumulative payout (including PRIs, loans, and administrative costs plus grants) falls to 5.21 percent and their grants-only payout to 4.37 percent.24 One idea suggested for donor-advised funds, since they get their full charitable deduction at the time of the irrevocable grant to the nonprofit sponsoring entity, is to require that the full DAF be spent out within, say, a ten-year period. Why wouldn’t a similar, perhaps somewhat longer but still definable spend-out requirement be applicable for private foundations?

As described earlier, donors like the former foundation director who established his family’s DAF at Fidelity are using the account like a charitable checkbook, except with a solid ability to look at giving trends and invest the assets with strategies fitting the donor’s charitable objectives. There is more of a charitable immediacy to these middle-income donors using DAFs than there is to the large donors setting up accounts larger than $100,000, or even larger donors establishing their own private foundations. While in some cases donors who had small foundations have now shifted them into DAF structures, eliminating many of the administrative headaches of foundations and reducing their administrative costs, there are affluent donors who use both foundations and DAFs together—and private foundations for which part of their payout is actually grantmaking to nonprofit DAF-sponsoring entities.

If there is a grants payout rate to be imposed on donor-advised funds—especially as they gravitate into instruments accessible for more moderate-income investors, with initial setup thresholds of $5,000 and the ability to make grants as small as $100—it is hard to imagine that it shouldn’t be accompanied by an increase in the mandatory payout of private foundations, whose grants payout often doesn’t top 5 percent. If there is going to be a mandatory spend-out requirement placed on all DAFs, it would be hard to justify without a concomitant spend-out requirement for private foundations that certainly exhibit no greater celerity in their distributions.

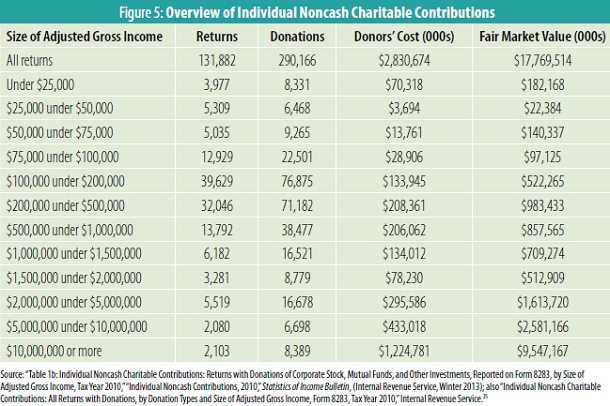

That individual donor opening up a $5,000 DAF could be looked at as the next rung up from individual givers making scattered checkbook donations. With the proliferation of mutual funds as investment vehicles, many taxpayers have appreciated stocks and mutual funds to donate, an easier means of doing so than selling the fund and donating the cash. In 2010, hardly a banner year for charitable donations due to the continuing effects of the recession, well over one hundred thousand taxpayers took charitable deductions for the donations of noncash stock or mutual funds to charities (see figure 5).

This is the background from which the donor couple profiled in this story emerge, possessing an appreciated stock that would be better used as a charitable donation than sold, cashed out, a portion lost to the capital gains tax, and then donated.

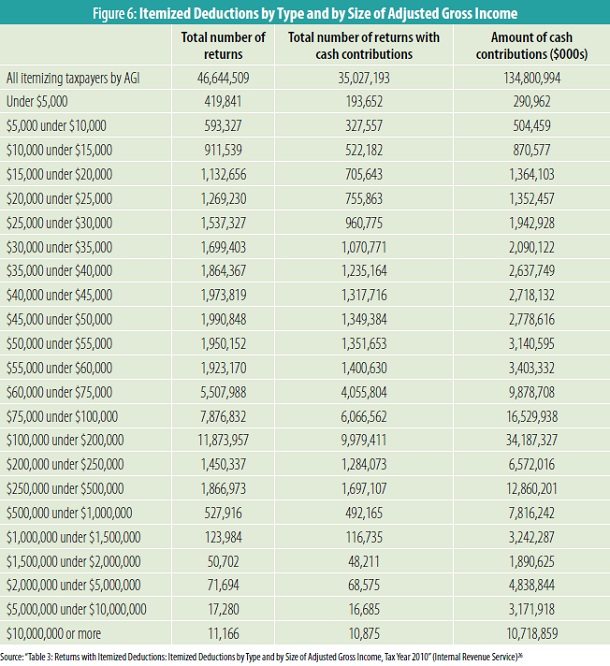

In addition to noncash contributors, there are cash contributors in middle-income earning areas whose charitable interests might be better served by a one-stop shop for charitable donations such as a DAF at a community foundation or a commercial manager, having grown out of a more reactive check-writing mode of charity. The Internal Revenue Service statistics of income show that for tax itemizers, again in 2010, the numbers attest to significant appetite and capacity for not insubstantial cash giving (see figure 6).

In 2010, itemizing taxpayers with incomes below $100,000 adjusted gross income were responsible for $49.5 billion in charitable cash giving. Charitable giving vehicles accessible to middle-income donors have a ready-made market in the charitable generosity of these itemizing taxpayers.

Conclusion

There are clearly some critics of donor-advised funds who see them as a subterfuge—a means of taking an immediate charitable deduction for a donation to a 501(c)(3) donor-advised fund manager, even though the funds are distributed to charities over a period of months or even years. There are critics who suggest that some donor-advised funds are simply warehoused capital, giving a maximum charitable deduction benefit to the donors while disbursing little to charities. Some even suggest that the high reported payout rates of donor-advised fund managers simply camouflage warehoused funds by aggregating all the funds they have under management—those that spend quickly with those that spend little or nothing. The statistics above and in this article’s accompanying sidebar (see below) show some of the composition and behavior of DAFs and DAF managers. What seem to be amiss in the donor-advised fund dynamic are effective oversight and transparency. If the problem of inactive accounts—possibly warehoused accounts—seems to be concentrated in DAF sponsors with a small number or only one DAF to manage, the issue seems to be one of IRS oversight. What are the bona fides of DAF sponsors whose track records involve sitting on a small number of DAFs? What kind of reporting is being asked of DAFs? Are those entities with sluggish DAF accounts getting the audits they would seem to need to verify that there is a potentially foundation-like reason for their slow or absent payouts?

In fact, as the CRS study notes, it appears that the IRS doesn’t collect information on specific DAFs, relying (for the sake of expediency and workload) on consolidated reporting by DAF sponsors rather than examining the payouts of the over 180,000 individual DAF accounts. Without individual-level reporting on DAFs, it is virtually impossible for the IRS to know if there are valid charitable purposes being carried out by DAFs, camouflaged as they are by the consolidated reporting of DAF sponsors. As the CRS study suggests, “Useful information that could be provided by DAF sponsors could include the share of their DAF accounts that made no distributions, the share that made distributions of less than 5%, or a general distribution of accounts across different payout intervals.” 27

The problem with this scenario is probably not on the part of legitimate DAF sponsors or managers. Rather, the limitation is the IRS. Already, the tax-exempt division of the IRS, embattled and severely underfunded, is barely able to keep up with its regulatory oversight. Sidestepping the need to review individual DAF accounts, the IRS simplifies its task by reviewing what is probably a small subset of the 1,828 DAF sponsors rather than being compelled to dig into the sum and substance of 180,000 accounts or more. That a considerable number of private foundations get by with payout rates that slip below 5 percent—and if they are hit with excise taxes, the taxes count toward their qualified distributions—suggests that the challenge for enduring DAFs on the up and up, both in terms of charitable mission and charitable outlays, is in the oversight part of the equation.

From an operating charity’s perspective, an equitable solution would be to place a spend-out requirement (say ten years) on DAFs that control $34 billion in assets, but also a spend-out requirement on private foundations that control the lion’s share of the $646.1 billion in assets controlled by foundation grantmakers.28 In reality, foundations won’t even contemplate a higher mandatory payout rate—some even hint that it should be lower than 5 percent—much less a mandatory spend-out requirement.

In the absence of changing the payout thresholds and timelines, Congress can give the IRS the resources to enable it to monitor 1,800 DAF sponsors and their 180,000 DAF accounts (in addition to the other responsibilities of the tax exempt unit of the Service) so that it could do a modicum of effective oversight of the spending of individual DAFs. And the nonprofit industry of philanthropic gatekeepers, the financial advisors who provide advice to even middle-income people about putting their savings into mutual funds or planning for retirement, can become much smarter about the middle-income asset owners in their communities and encourage them to use their charitable giving smartly and energetically for charitable advancement. There’s no reason for charitable giving—whether from a checkbook, a donor-advised fund, or a foundation endowment—to be lethargic.

Notes

- The Foundation Center’s Statistical Information Service, “Number of Grantmaking Foundations, 1975 to 2011” (New York: The Foundation Center, 2013), www.foundationcenter.org/findfunders/statistics/pdf/02_found_growth/2013/03_11.pdf.

- Kevin Laskowski, “Donor-Advised Funds ‘Based on Deception,’ Says Professor,” Keeping a Close Eye . . ., June 5, 2012, blog.ncrp.org/2011/09/donor-advised-funds-based-on-deception.html.

- Ibid.

- Laskowski, “When It Comes to Donor-Advised Funds, the Median Is the Message,” Keeping a Close Eye . . . NCRP’s Blog, September 9, 2011, blog.ncrp.org/2012/06/when-it-comes-to-donor-advised-funds.html.

- Mutual funds are a major component of U.S. stock market investments, comprising 28 percent of all corporate equity as of 2012. In the United States, 53.8 million households, or 44.4 percent of all U.S. households, own mutual funds. The median household income of mutual fund investors is approximately $80,000; their median household financial assets are $190,000. Statistics from Investment Company Institute, 2013 Investment Company Fact Book: A Review of Trends and Activities in the U.S. Investment Company Industry, 53rd ed. (Washington, DC: Investment Company Institute, 2013), 90–91, www.icifactbook.org/pdf /2013_factbook.pdf.

- A basis point is one hundredth of a percentage point, that is, 0.0001. One percent is 100 basis points. Fifty basis points is 0.0050, or 0.5 percent.

- National Philanthropic Trust, “Market Overview,” 2012 Donor-Advised Fund Report (Jenkintown, PA: National Philanthropic Trust, 2012), www.nptrust.org/daf-report/market-overview.html.

- Ibid., table 1.

- Ibid.

- The Foundation Center’s Statistical Information Service, “50 Largest Foundations by Assets, 2011” (New York: The Foundation Center, 2013), www.foundationcenter.org/findfunders/statistics/pdf/11_topfdn_type/2011/top50_aa_all _11.pdf.

- Laskowski, “When It Comes to Donor-Advised Funds, the Median Is the Message.”

- National Philanthropic Trust, “A Comparison of Sponsor Types,” 2012 Donor-Advised Fund Report, fig. 12, www.nptrust.org/daf-report /sponsor-type-comparison.html.

- Ibid., fig. 8.

- Kim Laughton, in an interview with the author, March 22, 2013.

- Sarah Libbey, in an interview with the author, March 15, 2013.

- Laughton, in an interview with the author.

- Libbey, in an interview with the author.

- Fidelity Charitable, Fidelity Charitable Policy Guidelines: Program Circular, last updated December 2012, 19, www.fidelitycharitable.org/docs/Giving-Account-Policy-Guidelines.pdf.

- Fidelity Charitable, “Trustees’ Philanthropy Fund,” 2012 Annual Report, accessed May 2013, www.fidelitycharitable.org/2012-annual-report/trustees-philanthropy-fund.shtml.

- Molly F. Sherlock and Jane G. Gravelle, An Analysis of Charitable Giving and Donor Advised Funds (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2012), 6, www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42595.pdf.

- Ibid., 17–18.

- Ibid., 14.

- Ibid., fig. 3, 18.

- The five community foundations are: The Chicago Community Trust, The New York Community Trust, Tulsa Community Foundation, Silicon Valley Community Foundation, and the Marin Community Foundation.

- Pearson Liddell and Janette Wilson, “Individual Noncash Contributions, 2010,” Statistics of Income Bulletin (Winter 2013), table 1b, 76, www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/13innoncash10.pdf; Internal Revenue Service, “Table 1: Individual Noncash Charitable Contributions: All Returns with Donations, by Donation Types and Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Form 8283, Tax Year 2010,” www.irs .gov/file _source /PUP/taxstats/indtaxstats /10in01cc .xls.

- Internal Revenue Service, “Table 2.1: Returns with Itemized Deductions: Sources of Income, Adjustments, Itemized Deductions by Type, Exemptions, and Tax Items, by Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2010,” www.irs.gov/file_source/PUP/taxstats/indtaxstats/10in21id.xls.

- Sherlock and Gravelle, An Analysis of Charitable Giving and Donor Advised Funds, 24.

- Steven Lawrence, Foundation Growth and Giving Estimates (New York: The Foundation Center, 2012), 2, www.foundationcenter.org/gainknowledge/research/pdf/fgge12.pdf.

|

Scope of the DAF Market The nonprofit complaint about donor-advised funds isn’t really about their payout—though nonprofits would like to have DAFs, private foundations, and other grantmakers disburse their moneys faster and reach people in need now rather than waiting on some artificially determined payout rate. They want to know the people behind the DAFs lodged in commercial funds or community foundations, so that they can submit direct applications. Unless the people behind DAFs want to be identified, their names are not disclosed, and technically nonprofits do not know which DAF accounts give to what nonprofits or causes (in the cases of entities such as Fidelity Charitable, the DAF managers increasingly report grant totals on their 990s—huge lists of disbursements, but without specific identification of the individual DAF accounts from which the grants are made). DAFs are instruments of individual giving (a donor’s giving account or giving checkbook), except that, unlike the case with many donors, they’re often larger: the average DAF size grew from $187,050 in 2010 to $211,067 in 2011.1 While the focus is often on the big three (or more) commercial sponsors of DAFs, the largest average-size DAFs are those managed by community foundations, according to the research of the National Philanthropic Trust (see figure 1).

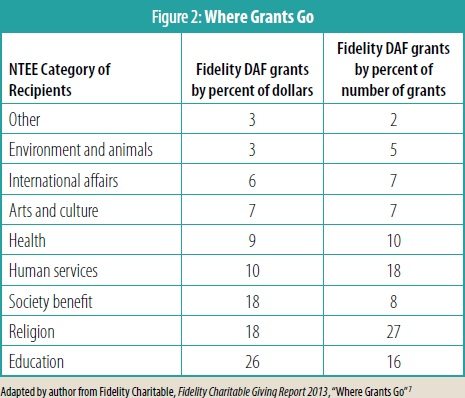

To most nonprofits, these are large charitable checking accounts, but ones that don’t look for unsolicited grant applicants. While the community foundations have general grant pools, and the commercial funds often have trustee-managed giving vehicles capitalized by DAF funds—funds left by a donor who may have died without leaving an heir or specific instructions for the dissolution of his or her accounts—nonprofits don’t really have an option of sending unsolicited proposals to Vanguard or Schwab, hoping for a grant. Increasingly, of course, all of philanthropy is headed in the direction of rejecting any and all unsolicited grant applications. The president of the Foundation Center, Bradford K. Smith, reports that 60 percent of independent, community, and corporate foundations do not accept unsolicited proposals, though perhaps the cold comfort of being able to see specific foundations’ Form 990s is preferable to the anonymity of DAF account holders.3 Chafing at the lack of transparency behind DAF accounts, nonprofits sometimes feel hamstrung with respect to accessing these charitable resources. The reality for nonprofits is that they have to treat DAFs as one of the tools used by major individual donors. Few nonprofits in their online fundraising pitches with donation buttons on their websites pitch to DAF accounts and structure it so that DAF holders can make it easy for them to make donations through their DAFs. The commercial managers are trying to find ways of making nonprofits more visible to donors without penetrating their anonymity, for example, such as Fidelity Charitable’s giving donors mobile apps with which they can make on-the-spot donations from their DAFs,4 or the new DAF giving widget generated by Fidelity and Schwab for nonprofit websites.5 Apps and widgets aside, ultimately the challenge is for nonprofits to understand and reach major individual donors. At Fidelity Charitable, the range of potential donors—94,000 of them, with almost 58,000 accounts—is reflected in their account sizes, ranging from a few thousand to more than a million. Fidelity Charitable’s recent profile of the giving of its DAF accounts is a very helpful instrument for understanding DAF donors that are likely to be more accessible to a broad range of nonprofits (Fidelity, like Schwab, has a minimum opening account threshold of only $5,000, and permits very small grants). The key characteristics for nonprofits to understand about Fidelity’s DAF donors include the following:6

It might surprise people to realize that only 5 percent of Fidelity DAF donors request that their gifts be given anonymously, meaning that nonprofits receiving DAF grants generally know who they’re benefiting from—much like their awareness of gifts from individual donors. There’s the rub—and the challenge. Unless there is a change in charitable giving law that requires disclosure of individual giving (remember, even direct corporate philanthropy is not disclosed if the grants are not made through corporate foundations), DAF donors are much like other individual charitable donors: neither more nor less anonymous than the people a nonprofit might want to solicit for other charitable donations—other than the fact that they make their grants via a better online platform that generally links their charitable giving to their personal investments. The result is that nonprofits have to see DAF donors as people of some moderate to significant wealth, people who make both planned and unplanned grants, and give to a rather typical array of charitable interests. They sometimes make grants from their pockets, sometimes from their DAFs, and in a small number of cases they have both DAFs and foundations for providing charitable and philanthropic gifts. While a nonprofit might not be able to send an application to Fidelity or Vanguard in order for them to pitch to their thousands of DAF accounts, nonprofits can make themselves more accessible to DAFs through new technology, and more accessible to major individual donors, who in all likelihood are giving through DAFs instead of their checkbooks.

NOTES

|

Rick Cohen is the Nonprofit Quarterly’s correspondent at large.