May 11, 2014; Wall Street Journal

Rural America can’t seem to get a break. According to Valerie Bauerlein in the Wall Street Journal, rural hospitals have long been financially challenged, but now the Obama administration says that rural hospitals have been getting federal subsidies they weren’t supposed to have gotten and should therefore should be cut out of $2.1 billion in Medicare payments for “crucial access” hospitals.

Rural hospitals aren’t being hit just by the Obama administration. Anti-Obamacare states that have refused to expand Medicaid coverage often cover large swaths of rural America. Rural hospitals in those states won’t be benefitting from the Medicaid payments that would have covered uninsured patients had those states taken advantage of the federally subsidized expanded coverage offer.

“We are in crisis mode,” said Maggie Elehwany, vice president of the National Rural Health Association, summarizing the conundrum facing rural hospitals. “We’ve got gale-force winds coming from one direction, the tide coming in from another and it’s really hitting these small hospitals who operate at tiny margins.”

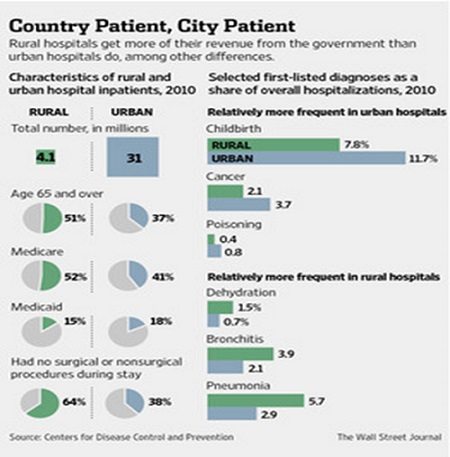

The Medicare hit and Medicaid loss are significant for rural hospitals, which receive about 60 percent of their revenue from government sources. The following graphic from the WSJ article shows clearly how much larger a proportion of rural hospitals’ patients are senior citizens and, consequently, how much larger their Medicare receipts are.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As a result, rural hospitals, roughly about 2,000 in existence, are beginning to succumb to financial pressures. More than a dozen closed in 2013 and additional rural hospitals seem to be on their way to shutting down this year.

Even without these rural hospital financial pressures and closures, the reality is that health care in rural areas of the U.S. is hardly oversupplied with providers and facilities. For example, in North Carolina, 45 percent of the population lives in rural communities, but only 18 percent of the state’s primary care doctors have primary practices in rural communities. As a result, people in rural communities like those in Western North Carolina have to turn to nonprofit community health clinics, such as the Celo Health Center in Yancey Council.

The Celo Health Center is distinctive, located on land owned in common by the Celo community land trust (formally Celo Community, Inc.), founded largely by Quakers and pacifists before World War II. The 1,200-acre CLT houses only about 40 households, but the Health Center serves a much broader geography. Nonetheless, Celo’s distinctive history, culture, and governance don’t overcome the essential challenge of attracting doctors and accessing resources to ensure quality health care provision for rural citizens.

Why emphasize the needs of rural communities for healthcare? The statistics on poverty make the case. Between 2007 and 2011, of the nation’s 703 high-poverty counties, 571 were nonmetro, mostly in the South and Southwest, and often with high concentrations of blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans. The number of high poverty nonmetro counties had increased 30 percent compared to 2000.

A study from the National Rural Health Association detailed the higher incidences of many kinds of health problems among the rural poor, but noted that the problem is exacerbated by the shortage of medical personnel in rural areas:

“Severe physician shortages exist in rural areas, and the trends are not changing enough to compensate for the demands of health services… Data shows that the majority of physicians end up in practice where they were trained and completed their residency programs, but new estimates indicate only 3 percent of new graduates will choose to practice medicine in rural or remote areas…Without an adequate number of health care providers available, many rural residents will remain underserved and without primary or preventative care.”

—Rick Cohen