—“How Anti-Trump Psychiatrists Are Mobilizing Behind the Twenty-Fifth Amendment,” Jeannie Suk Gersen, The New Yorker.

This past summer, NPQ took a look at the history, mechanics, and consequences of impeachment. It continues to be a discussion topic which most people think they understand, but haven’t really studied. Recently, more attention has been drawn to the potential for declaring the president unfit to lead by invoking the process included in the U.S. Constitution’s Twenty-Fifth Amendment. While impeachment is far from simple, and includes some landmines most people are unaware of, it is a far easier and less potentially dangerous process than using the Twenty-Fifth Amendment to remove a president from office.

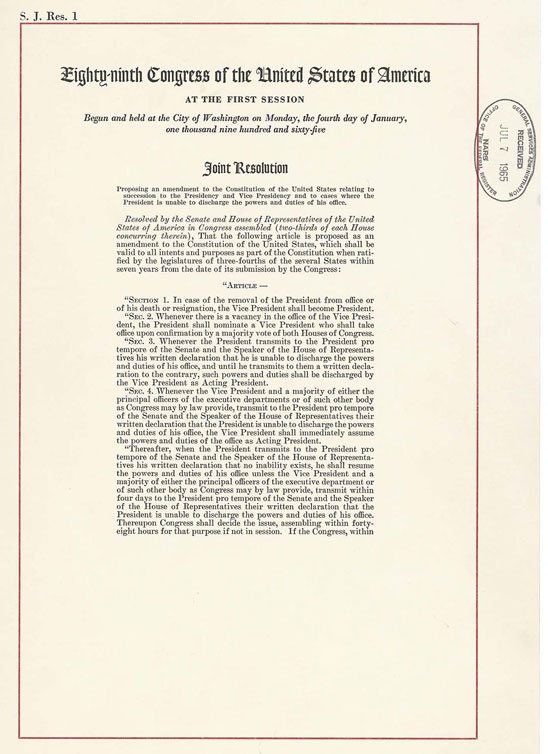

The Twenty-Fifth Amendment was developed, passed by Congress, and approved by the required three-fourths of state legislatures during the 1960s as a way to further define and establish the process for presidential succession. The relatively recent death in office of Franklin Roosevelt, the heart attack and stroke suffered by Dwight Eisenhower, and the assassination of John Kennedy all influenced its development. While the Constitution addresses presidential succession in Article II, it was believed a more comprehensive and methodical approach was needed to replace the original language.

Briefly, the first three of the amendment’s four sections address: 1) the succession of the vice president to the presidency; 2) a provision allowing the president to fill a vacant vice presidency by nominating an individual subject to a majority vote by both houses of Congress; and 3) the option for the president, by letter to Congress, to temporarily and voluntarily transfer the duties of the office to the vice president should he anticipate becoming incapacitated (such as undergoing surgery under anesthesia) and recover them once the incapacity is no longer present. All three of these provisions have been used successfully since the Nixon Administration.

Unlike the first three sections of the amendment, Section 4 has never been tested, and that is the section people are discussing today. Here it is, in full:

Section 4. Whenever the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall immediately assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.

Thereafter, when the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that no inability exists, he shall resume the powers and duties of his office unless the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive department or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit within four days to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office. Thereupon Congress shall decide the issue, assembling within forty-eight hours for that purpose if not in session. If the Congress, within twenty-one days after receipt of the latter written declaration, or, if Congress is not in session, within twenty-one days after Congress is required to assemble, determines by two-thirds vote of both Houses that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall continue to discharge the same as Acting President; otherwise, the President shall resume the powers and duties of his office.

The initial takeaway from reading Section 4 is how difficult it would be to execute in the clearest of circumstances.

The process begins when the vice president and a majority of the cabinet agree to declare the president unable to discharge the duties of the office (to date, Congress has made no provision for an alternate body to make this determination). The vice president’s cooperation is required; the cabinet may not act without the vice president’s agreement. Having made this determination, they are required to send a letter (“written declaration”) notifying the House and Senate.

If the president disagrees with the declaration of the vice president and cabinet majority, he or she can send their own letter to Congress and resume work immediately. However, if the vice president and a majority of the cabinet send a second written declaration to Congress within four days disputing the president’s self-assessment, Congress must be called into session and decide within three weeks who is correct. A two-thirds vote of both the House and the Senate is required for Congress to, in effect, overrule the president’s own self-assessment, agree with the vice president and the cabinet and declare the president unable to serve. Once such a vote was taken, its effect would be immediate.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

If the foregoing isn’t enough Constitutional drama, intrigue, and complex process for you, it’s really just the beginning.

“Unable” is a key word in Section 4. The language doesn’t envision a coup d’état based on a power grab by a dissident faction or a change in leadership based on ideological or policy differences. Based on the available legislative history, it specifically envisions a medically determinable condition sufficient to satisfy a potentially large group of non-medical politicians (not to mention the general public).

Medicine is still more, or at least as much, art as it is science, particularly since the science of medicine keeps changing. It’s relatively easy to look at a person in a coma and say they’re unable, but what about a person in the early stages of Alzheimer’s? If patients with neurodegenerative brain disorders like Alzheimer’s are difficult to evaluate through the lens of “presidential ability,” many cognitive disorders and mental illnesses are even more problematic to assess. Imagine a president with a mental disorder that is controlled successfully with medication. Would they be “able” if they take their prescriptions? Would they still be “able” if they decided to stop taking medications for a period of time?

Imagine the chaos of a public debate centered on whether the president is mentally fit to serve while the nation and the world watches, and how the debate would magnify if the president resisted. Dueling experts on cable TV practicing medicine without ever examining the patient. A president either unwilling to be examined or insisting on hiring his own experts who would, presumably, defend the president’s ability. There are no regulations specifying who can advise the vice president, the cabinet, and/or Congress about the president’s physical or mental health as they consider the president’s ability to serve.

At least some of the people envisioned to decide whether the president should be removed from office using Section 4 can be presumed to have political motivations that might influence them to either support or oppose a determination of the president’s ability to execute the duties of the office. Some may be swayed by considerations of the vice president’s party affiliation, ideology, temperament, or other personal factors. Some may use Section 4 as a partisan political tool to thwart or advance their own political agendas, with presidential ability to serve coming in a distant second place in their deliberations.

Since Section 4 has never been used, acts performed under its provisions are subject to judicial interpretation. While the US Supreme Court may be very reluctant to intervene in the actions of Congress specifically, there is ample precedent for the court to examine and rule upon the processes and decisions made by cabinet officials performing their professional duties. Even with expedited access to the Supreme Court and quick rulings, court challenges could delay final actions for some time, further exacerbating the nation’s Constitutional crisis atmosphere. The lack of precedent, the weight of the immediate questions to be resolved, and the historical effect of precedent being created in the midst of crisis combine to argue for simultaneous, yet inconsistent emphasis on both deliberation and speed.

As NPQ expressed in its article on impeachment, it’s important to stress the crucial role played by the vice president in assuring a smooth transition of power should the president be removed from office. Without strong support for the vice president to rebuild the executive branch (assume at least a few cabinet resignations in the wake of exercising Section 4 provisions of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment) and provide leadership in the aftermath of crisis, the country could face sustained turmoil. Most importantly, a new vice president would need to be confirmed quickly using Section 1. The reasons why are especially frightening and point to one of the few ways in which the government of the United States hinges on the vice presidency.

The Presidential Succession Act of 1947 envisions a line of succession including the vice president, Speaker of the House, president pro tempore of the Senate, and cabinet secretaries in chronological order of their respective department’s establishment. However, there are good arguments to be made: 1) that the succession act is unconstitutional; 2) that Congress has previously acted in defiance of the succession act; and 3) that the National Defense Act of 1947 conflicts the succession act and envisions a different order of presidential succession, setting up a competition between the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Defense.

Finally, we have the technicality that any vice president who replaces a president under the terms of Section 4 is actually not the president, but, rather, the “acting president,” acting in that capacity until a new president can be elected. This would, presumably, happen at the next general election. However, there are many legal questions associated with the “acting presidency.” For example, there is no case law interpreting whether serving as acting president counts toward the term limits imposed on candidates for the presidency. Does the acting president still hold the office of vice president and preside over the US Senate until a new vice president is confirmed?

Presidential succession is largely uncharted and unresolved legal territory, and especially so when considering the Twenty-Fifth Amendment and Section 4 in particular. It provides ample fodder for multiple federal lawsuits requiring resolution. Worse, it gives abundant opportunity for politicians, pundits, and the public to dispute legal interpretations and further erode public confidence in the stability of the federal government as an institution.

So, is the Twenty-fifth Amendment a viable option for activist groups that sincerely believe that there is an underlying disease or incapacity behind much of the incomprehensible communiques coming out of the White House? We leave that up to you, but we would love to hear from anyone who has an alternate interpretation of the viability of that option.