This article comes from the winter 2020 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly.

History has proven that, in the absence of grassroots advocacy, policy can have significant, long-lasting destructive effects, especially on marginalized, disenfranchised communities. Nonprofits are well positioned to offer solutions and policies that address the spectrum of challenges our society faces—and in the current environment, it is imperative that nonprofits engage in policy advocacy, and that funders support them to do so.

While some may think advocacy simply means politics and protest, it encompasses a far broader variety of actions that nonprofits and funders can incorporate into their work, including the following:

- Developing strategic partnerships and coalitions

- Organizing, mobilizing, and creating spaces for communities to be empowered

- Advancing education campaigns to ensure an informed public

- Influencing through lobbying (yes, nonprofits can lobby) and sharing perspectives regarding laws, legislation, regulations, and government budgets being proposed, particularly at the state and local levels

- Making use of impact litigation

- Leveraging expertise to bring about change

Failure to engage in policy advocacy results not only in missed opportunities toward authentic solutions but also maintains the status quo set forth by others. A nonprofit that provides mental health services to students, but does not engage in the local city budgeting process to advocate against budget cuts to these services, helps to facilitate an environment where underfunding prevails, resulting in a dearth of vital services. An example of the opposite approach is the New York nonprofit Cypress Hills Development Corporation, which has used its platform to advocate against such cuts, and in doing so, enlisted the support of New York City Council member Mark Treyger to help advocate for support in the city budget.1

Here are six effective advocacy steps nonprofits and their funders can take:

1. Collaborate and Build Partnerships

We don’t like to talk about it, but the nonprofit sector suffers from extreme competition. Resources are limited, and nonprofits—even in (indeed, especially in) the same mission area—must compete with one another to stay in business. In this environment, collaborations are often inauthentic and ineffective. We need to break down the competitive silos in the sector and orient our efforts around collective action and shared power, and funders must work to eliminate this toxic dynamic. In other words, nonprofits build power in numbers and strengthen one another in an environment where systemic change takes time and where victories do not come easily.

Even though there is often a narrative about lack of or limited resources, the nonprofit sector wields a significant amount of influence and power, which as of 2017 (the latest data available) employed nearly 12.5 million people.2 Further, according to the Urban Institute, as of 2019 the nonprofit sector had total assets reaching $3.79 trillion dollars (nonprofits registered with the IRS); in 2018, charitable contributions reached $427.71 billion; and in 2016, the sector contributed an estimated $1.047 trillion to the U.S. economy, comprising 5.6 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).3

And let’s be honest: the government often relies on human services nonprofits to provide vital services that government is responsible for providing. It’s up to nonprofits to recognize this, partner on common issues—through coalitions, strategic partnerships, joint ventures, and other informal and formal designs—and claim power as a united force.4

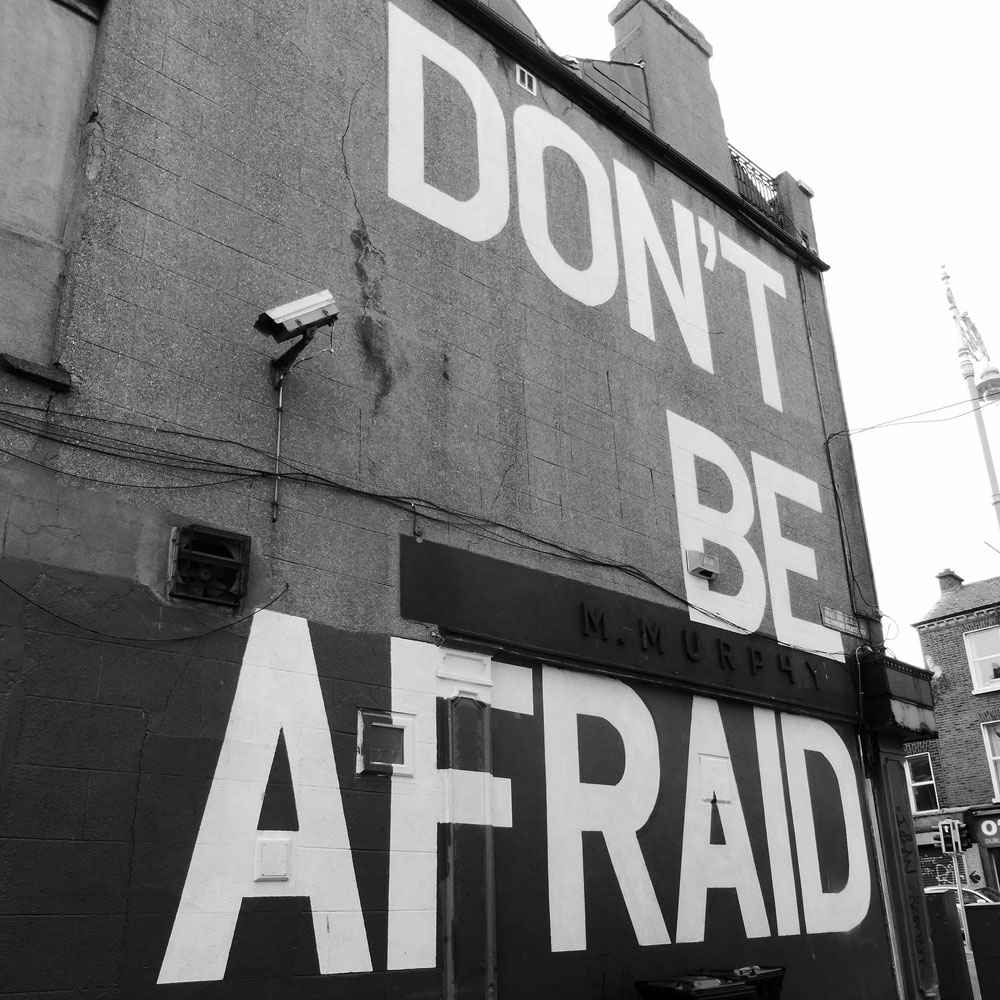

2. Stop the Fear, Be Informed, and Ask the Bigger Questions

In order to address what prevents so many nonprofits and foundations from engaging in policy, it is important to ask, “What/who are we afraid of?” Generally, organizations are most worried about upsetting their funders, donors, and board members, and this who connects to the very power dynamics that inhibit the use of policy as a strategy for increased equity and justice.

It can feel like too great a risk to jeopardize funding sources, as these enable nonprofits to do their work. However, now is a time for nonprofits and funders alike to strike while the iron is hot. Philanthropy is having a reckoning of its own, and is rethinking some of its old practices and who and how it funds. This is a perfect opportunity to push past the fear around funding and have honest conversations with funders, donors, and board members about what is needed to have true impact.

Some organizations also fear losing their 501(c)(3) status, or fear facing IRS penalties of excise taxes—but these fears are unfounded. There is an abundance of websites, experts, and organizations whose job it is to help support organizations with their policy efforts.5 Regarding the restrictions placed on the sector for its use of financial resources to effect political change, why this is the case is also worth a deeper conversation. It is interesting to note, for example, that in a five-year period (2007–2012), “200 of America’s most politically active corporations spent a combined $5.8 billion on federal lobbying and campaign contributions. A year-long analysis by the Sunlight Foundation suggests, however, that what they gave pales compared to what those same corporations got: $4.4 trillion in federal business and support.”6

Nonetheless, to be clear, as the National Council of Nonprofits states, the “prohibition against political campaign activity (defined as ‘supporting or opposing a candidate for public office’) is SEPARATE from lobbying or legislative activities, which charitable nonprofits ARE permitted to engage in.”7

At the end of the day, we must break through the mindsets and internalized ways of working that are motivated by scarcity and pandering to power.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

3. Intentionally Build Advocacy into Nonprofit Work

What if, when a nonprofit was created, a strategy for policy work was expected along with the budget and bylaws? What if policy advocacy was a necessary component included in strategic and other planning efforts? What if nonprofit board members and staff received regular training in advocacy and were expected to engage their networks in this work? What if nonprofits listened to their communities and aligned policy with equity and justice?

Asking these questions gives nonprofits the opportunity to reimagine their work and openly enlist the support of willing funders, and it results in a world where advocacy is a given. The possibilities are many. We must stop treating policy work as a “nice to have” or another “I’ll get to it when…,” and instead make it the charge of all nonprofits to engage. Building advocacy into nonprofit work through intentional planning normalizes it.

4. Diversify and Build Inclusive Organizations Tasked with Social Change

We’d be remiss if we didn’t specify that the nonprofit sector as a whole must do more to ensure it actually reflects the communities in which nonprofits are situated and serve, as these are the organizations that are truly in proximity to the challenges and, ultimately, the solutions. If “79 percent of Congress is white,”8 87 percent of all nonprofit executive directors or presidents are white,9 nearly 79 percent of nonprofit board members are white,10 and “92 percent of foundation presidents and 83 percent of full-time staff members are white,”11 why are these the people in charge of creating change for communities that look nothing like them? This homogeneity in power creates homogeneity in norms, practices, networks, and decision making that have become hegemonic and that reproduce practices of colonization, all from a sector created to “do good.” Tené Traylor, who oversees grantmaking at the Kendeda Fund, put it best when she said, “We still trust white folks to tackle black folks’ problems.”12

This chasm of representation is important, because core to the work of policy and advocacy is self-interest: we fight for what impacts us or those we care about. To stop perpetuating inequity, nonprofits and funders must examine their internal makeup and practices and ensure that Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities are a part of the infrastructure as staff, leadership, and board members.

5. Fund Policy Work, Movement Building, and Black-, Brown-, and Indigenous-Led Organizations

While there are myriad power paradoxes in the nonprofit sector, one that is most prevalent is the chasm between those closest to the pain and those closest to the resources. How is it that the least amount of support goes to those leaders, organizations, and communities that are suffering the most? Far too often, the organizations closest to the lived experience of underinvested and undervalued communities, and best positioned to engage in policy and movement building, have been left teetering on the edge of existence.

Lori Villarosa of the Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity (PRE) hit the nail on the head when, regarding COVID-19 response, she wrote: “Small grassroots organizations with direct roots, access, and accountability to their communities have been busy taking calls, visiting affected residents, and handing out supplies, while dealing with the challenges of their own families. As a result, they are rarely the first in line in responding to funding opportunities…. The likely result: philanthropy ends up too often falling short of desired outcomes, while racial inequity and injustice are all too regularly perpetuated.”13

While there has been a substantial increase recently in the amount of funds given to movement organizations and Black-, Brown-, and Indigenous-led organizations, prior to the recent outcries for support, funding that reached people of color has been less than 10 percent and stagnant.14 And, one must wonder what will happen to those funds in the future as other priorities emerge?

Funding must be directed to reach beyond program and service work and drive systemic change. While as a sector we struggle to assign capacity to policy work, year after year we continue to lose progress, and entire swaths of our sector suffer.

6. Empower Communities to Engage in Policy Work

Regardless of budget size and staff size, nonprofits have the power to come together and share information, and with such tools at their disposal, can be a part of the critical work of convening, sharing with, and empowering their communities to engage in policy work. Many of our greatest societal changes have come directly from the people, rather than those with the most money or political power, and nonprofits can certainly be a link connecting communities that have traditionally been marginalized from the levers of power.

By ensuring that the community at large is kept abreast of how the environment is shifting, so that they are ready to respond, nonprofits will meet the responsibilities they have to their constituents by centering them in the policy work.

…

What if the nonprofit sector activated its powerful voice and the voices of the communities we serve, and shaped the policies and the resulting practices to create deeper, more sustainable change? What if funders supported nonprofits to do that work? We say we want to create a more just and equitable world. The time to do this work is now.

Notes

- Reema Amin, “In financial crisis, NYC cut $707M from its education budget. These programs will feel the effects,” Chalkbeat, July 22, 2020.

- Lester M. Salamon and Chelsea L. Newhouse, The 2020 Nonprofit Employment Report, Nonprofit Economic Data Bulletin no. 48 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies, June 2020).

- NCCS Project Team, The Nonprofit Sector in Brief 2019 (Washington, DC: National Center for Charitable Statistics, Urban Institute, June 18, 2020).

- “Partnerships and Collaboration,” The Bridgespan Group, January 1, 2015.

- See, for example, Advocacy and Lobbying, NYLPI Nonprofit Toolkit (New York: New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, 2020).

- Bill Allison and Sarah Harkins, “Fixed Fortunes: Biggest corporate political interests spend billions, get trillions,” Sunlight Foundation, November 17, 2014.

- “Political Campaign Activities—Risks to Tax-Exempt Status,” National Council of Nonprofits, accessed November 4, 2020.

- John W. Schoen and Yelena Dzhanova, “These two charts show the lack of diversity in the House and Senate,” CNBC, last modified June 2, 2020.

- Susan Medina, “The Diversity Gap in the Nonprofit Sector,” PND (Philanthropy News Digest), June 14, 2017.

- “Nonprofit Boards Don’t Resemble Rest of America,” NonProfit Times, February 20, 2018.

- Paul Sullivan, “In Philanthropy, Race Is Still a Factor in Who Gets What, Study Shows,” New York Times, last modified May 5, 2020.

- Anastasia Reesa Tomkin, “How White People Conquered the Nonprofit Industry,” Nonprofit Quarterly, May 26, 2020.

- Lori Villarosa, “COVID-19: Using a Racial Justice Lens Now to Transform Our Future,” March 30, 2020, Nonprofit Quarterly.

- What Does Philanthropy Need to Know to Prioritize Racial Justice? (Washington, DC: Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity in partnership with Race Forward and Foundation Center, 2017.