Founded in 1936, the Rudolf Steiner Foundation is best known for its Waldorf education model, which focuses on whole child development. RSF Social Finance (RSF), which the foundation launched in 1984, is less well known. Still, RSF has been influential, making over $600 million in loans, grants, and investments in socially oriented businesses to date.

In 2018, the San Francisco-based nonprofit originated $80 million in loans and grants to 695 firms. According to its CEO, Jasper van Brakel, about 60 percent of its activity is with nonprofits, with for-profit firms comprising the other 40 percent. Loans under its management at the end of 2018 totaled $225 million.

Money is raised both through investment notes (which act like uninsured certificates of deposit, can be bought for a minimum of $1,000, and must be held for at least three months) and through donor-advised funds. RSF’s 2018 annual report indicates that food and agriculture businesses represented nearly half (49 percent) of lending. Thirty-eight percent went to education and arts, 12 percent to climate action, and one percent to workforce development and social finance.

So far, this sounds similar to a community development financial institution (CDFI), a field with $185 billion in assets nationally that NPQ has profiled before. But RSF has a few unique wrinkles. CDFIs typically make capital available to communities of color and low-income communities, but their lending products often look quite similar to mainstream banks. RSF seeks to change the process of lending and grants itself.

As van Brakel explains, while it is all well and good to say shareholder maximization will no longer govern businesses, declarations of good intent from business leaders are unlikely to suffice. “We need actual tools to make it happen that are not romantic or philosophical, but practical,” van Brakel emphasizes. RSF, Van Brakel adds, seeks to develop a few of those tools.

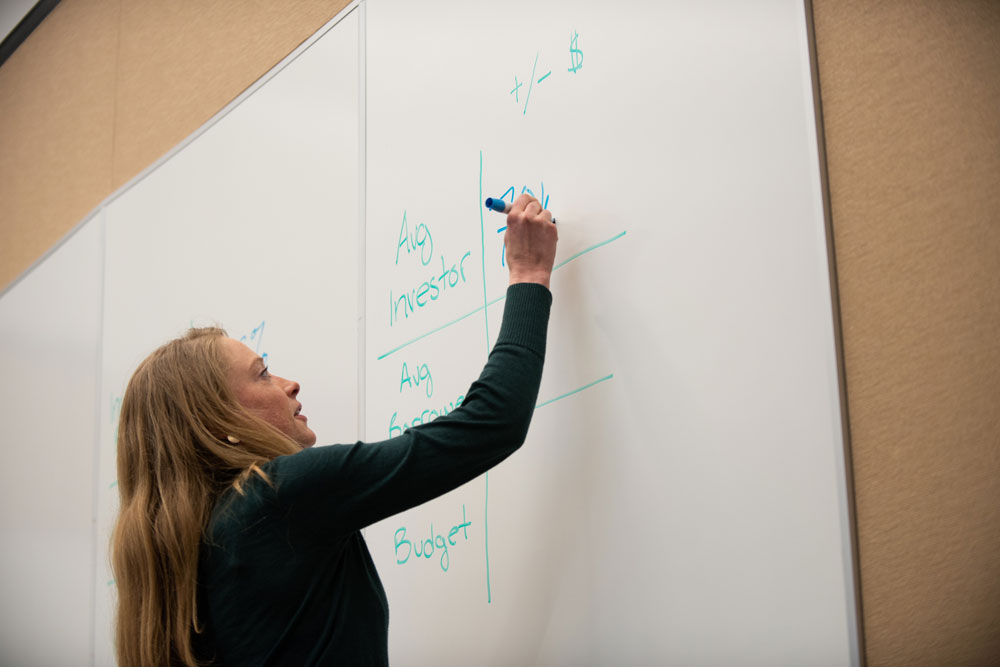

One such tool concerns how RSF sets its interest rates, both for savers and borrowers. Typically, a bank—even a socially minded CDFI—sets interest rates based on an internal staff assessment. RSF, by contrast, sets its interest rates through a process known as a “community pricing gathering.” As Van Brakel explains:

We get our investors and borrowers around the table, not all of them, but we get a cohort together. Then, we talk about what the interest rate should be for the next quarter. We talk about this collectively. Usually investors want a higher interest rate and borrowers want a lower interest rate. But once you put people around the table, investors start asking borrowers, “What would the impact be if the rate goes up or down?” It turns things around. It makes it tangible that we are doing this together. We meet quarterly….It’s been successful for 10 years.

For example, on April 1, 2018, RSF raised its interest rate by one-quarter of a percent (from 5 to 5.25 percent) and also increased its investor payout from 0.75 percent to one percent. RSF’s margin remained the spread—namely, 4.25 percent. But this decision came out of a meeting held in Seattle the previous month. As RSF’s website details:

At the March pricing gathering in Seattle…some borrowers expressed a sense that they could tolerate an increase without disruption to their business. There was some sense from the nonprofit borrowers that since they have less control over income streams and set budgets once a year, a rate increase would be difficult. Yet, there was…a reticent willingness to support a small increase.

[…]

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

One former borrower, now an investor, stated that if the rate went up, they would increase the balance of their fund.

A second tool employed by RSF is what the nonprofit calls a shared gifting circle. Van Brakel explains that, “This requires a donor to give up their power and to make their grant to a community of organizations who themselves decide who gets the money.”

“A donor might say, ‘I want to give $100,000 towards indigenous community initiatives in the Midwest,’” Van Brakel elaborates. “Rather than program officers, or people within RSF, determining where the money goes, we gather [potential] grantees around the table. Here’s a $100,000 check—we have designed a process around sharing and making a decision. Please tell us where the money should go.”

RSF has practiced such participatory grantmaking for about ten years. The RSF’s website details one such example, its second annual Women’s Capital Collaborative (WCC) Shared Gifting Circle in October 2018. Here the process began with past Circle participants, WCC funding recipients, RSF staffers, and community partners. Out of 39 organizations identified this way, seven Bay Area organizations, all focused on empowering girls, came together “to determine how to allocate $126,000 in gift money to support each other’s work.”

RSF has practiced collective interest rate-setting and participatory grantmaking for a decade, but the nonprofit is also developing some new tools. In particular, van Brakel says RSF wants to put more energy into promoting “mission-first” business structures. The idea, van Brakel says, is to support businesses that not only talk about stakeholders, but very explicitly anchor that in the structure, ownership, and governance of the business, “so that profit can serve its purpose, rather than the other way around.”

As van Brakel explains, the idea is to “separate the economic rights and the governance rights…the goal is to protect mission so that it cannot be corrupted. To put the steering wheel of the company in the hands of stakeholders.”

Van Brakel adds, “A business owned by a not-for-profit is one way to do it,” a theme that has been raised in NPQ both by Douglas Rushkoff and Jennifer Hinton. Another mechanism is the “so-called golden share.” This, Van Brakel explains, is a mechanism where you have different classes of shareholders, in which the golden shareowner has full governance rights, while private shareholders have economic rights [i.e., a right to a return on profits], but do not have governance rights (or have limited rights).

Van Brakel points to his native Europe to illustrate the viability of this governance model. “In Denmark, about 20 percent of gross domestic product is generated by foundation-owned businesses,” van Brakel says. In Campden FB, Scott McCulloch writes that an estimated 1,300 such businesses exist in Denmark. McCulloch adds that “Some experts estimate the value of listed companies controlled by Danish foundations at about 68 percent of total market capitalization of the Copenhagen Stock Exchange.” The foundation ownership form is also common in other Scandinavian countries.

Never heard of a foundation-owned firm? Well, perhaps you have heard of Ikea, which, notes Steen Thomsen, a professor at Copenhagen Business School, is owned by the Stichting INGKA Foundation, “one of the largest charitable foundations in the world.” Other foundation-owned firms whose names might be familiar include Bertelsmann, Heineken, Robert Bosch, Rolex, the Tata Group, and Carlsberg. In the US, few such examples exist. Direct ownership of firms by foundations has been banned since 1969. Grandfathered in is the Otto Bremer Trust, which has a 92-percent ownership stake in Bremen Bank, a $13-billion financial services company founded in 1943, with branches in Minnesota, North Dakota, and Wisconsin.

Foundation-owned firms, notes Thomsen, are common in Denmark and Sweden because “high wealth taxes historically encouraged business owners to seek non-standard ownership forms.” On balance, Thomsen writes, foundation-owned firms have similar profitability to non-foundation-owned firms. Thomsen adds that they also “survive longer. They take less risk. They treat their employees better—pay them more, retain them for longer, and engage more in work-life balance. And of course, they donate their surplus to charity rather than paying it out to investors.”

What might make such companies more common in the US? Obviously, a legal change would be required to have foundations own companies directly. Of course, nonprofit-owned businesses are already common in the US, and other forms of business, like multi-stakeholder cooperatives such as Fifth Season Cooperative in Wisconsin, also implement many of the shared principles van Brakel advocates. This expanding form of cooperative typically is structured to have multiple classes of membership, such as producers and buyers, who have to negotiate among themselves to achieve a common good. Still, van Brakel recognizes that “a systems-change component” would be needed, far beyond RSF’s loans and grants, to achieve such a transformation.

Van Brakel concedes that RSF does not engage in political advocacy, but the nonprofit does seek to be an advocate “in the social enterprise and impact investing space.” One step that RSF has taken, van Brakel says, is to create a nine-month integrated capital fellowship program. To date, van Brakel adds, three cohorts with 74 fellows total have participated. RSF also sponsored a white paper, published last month, titled State of Alternative Ownership in the US: Emerging Trends in Steward-ownership and Alternative Financing, that articulates this philosophy of what RSF calls “steward ownership.”

RSF’s approach, van Brakel contends, is unlike many in impact investing. Too often, van Brakel explains, impact investing means still maximizing profit, “but let’s do it with stuff that is less bad.” What RSF is seeking to put forth is a completely different paradigm, van Brakel says. The goal, he adds, is to completely “change the whole conversation around money.”