Editors’ note: This article, first published in print during October-1996, has been republished for Nonprofit Quarterly with minor updates.

Few things are likely to be as frustrating to paid staff as when board members come unprepared for meetings. Staff are especially frustrated if they have diligently prepared for a board meeting and carefully sent out essential material in plenty of time for board members to read it so that they can make intelligent choices on the actions to be taken. Too often, a quarter of the board members don’t come to the meeting, another quarter forget to bring their board packets, and no one shows evidence of having actually read any of the conscientiously prepared materials.

“My board members are so thoughtless,” reported one exasperated director, “that they will sit down at the meeting and open up the envelope of stuff I sent them for the first time — and they do it right in front of me!”

These experiences highlight the fact that board members and paid staff are operating from two entirely different frameworks. Board members work for an organization in their “spare” time or “free” time. Staff people work for the same organization using their “paid” time. For all their thoroughness, staff people often do not take the board member’s frame of reference into account, which is the source of staff frustration. No matter how well-meaning, dedicated, sophisticated, compulsive, or responsible board members are, they simply will not expend the amount of time and effort required to balance the time and effort a paid staff person has put in on behalf of helping the board run the organization.

This is an inherent, unresolvable inequality. However, it can be mitigated by using certain techniques, built on principles of human nature, to increase board members’ participation. This article explores two points at which staff can work to narrow the gap: before the board meet-ing and at the board meeting.

BEFORE THE BOARD MEETING

1. Use the installment plan. Most staff people realize that it is essential for board members to be familiar with the background, complexities, and options involved in decisions they will need to make at the meeting. Having materials ahead of time gives board members a chance to read them in advance, make notes, and understand what is being asked of them. However, most staff know that board members often do not read material sent in advance. The secret is to send the materials in “chapters.” Imagine that you are serializing your advance reading for the board meeting. First, you send the minutes from the previous meeting immediately after that meeting. Two weeks before the next board meet-ing, you send a budget report. A few days after that, you send an annotated agenda. One or two days before the meet-ing, you send another piece of information. Some board members will complain that they want all the materials sent at once. Others will grumble about the postage cost of these piecemeal mailings. But each of them will have read at least some of the materials and many will have read all of them.

2. Be personal. Remember the direct mail adage that people love to read about themselves? Whenever you can, add a personal note to a mailing, but not always on the front page of the information. For example, in a summary of two choices for an ongoing campaign, one staff person wrote a note on page 2 to two board members (“Really think about this — your comments will sway the group”), a note to one member in the middle of page 3 (“I think this was your idea, wasn’t it?”) and notes at the beginning and end of the docu-ments to the other two board members. When the board meeting came, each board member had read the whole document. (If you don’t think board members will look inside for personal notes, add a Post-it to the front of the document that will direct them to look inside: “See page 2.”)

This is also a useful strategy when developing the mate-rials themselves. For example, a report on the fundraising committee’s plans — even if a staff person wrote it — ought to be sent to the chair of the fundraising committee for his or her signature before it goes out to the rest of the board. Since most people will not sign something they haven’t read, staff will know that the chair read the material. Committee reports can refer to members of the committee by name, such as, “At the suggestion of Peggy R., we decided to move the mail appeal from October to September,” or “Gene P. solved our rug problem by agreeing to ask Joe’s Carpets and Floor Coverings to donate one.” When people notice that their names will appear in material sent for advance reading, they will be more likely to take the time to read it.

3. Invite action. Whenever possible, without being artificial, require some action from board members prior to the meeting that will cause them to read the material. This can be stated in a personal note, “George, I am assuming you will give the Personnel Committee report. Call me if you need more information than is in here.” Or, “Penny, can you speak to Lorraine and make sure we are using Johnson Park Activity Center for our annual meeting? Then we can announce that at the board meeting. I’ll call you later about the schedule for the invitations.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

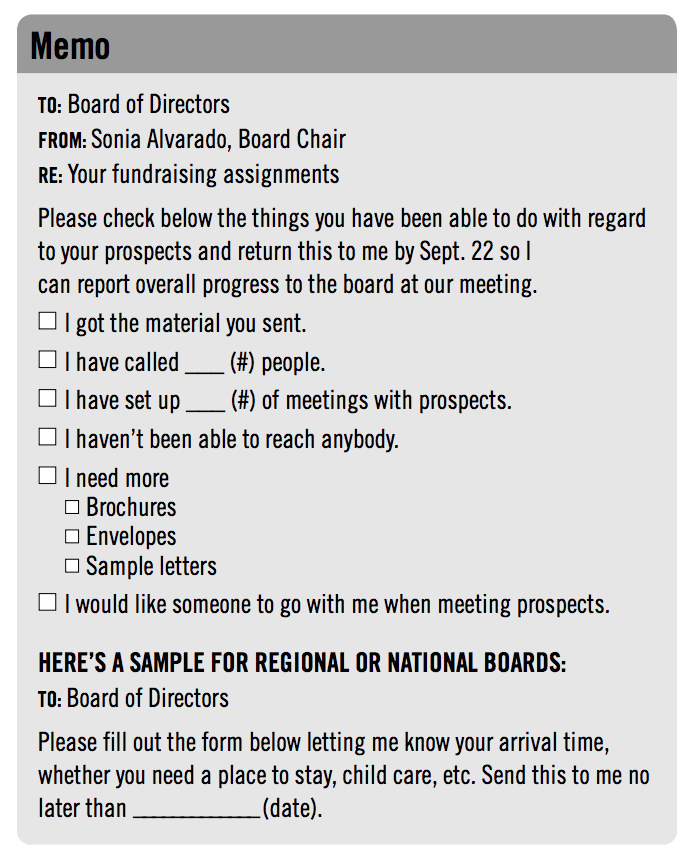

Another option is sending a form that board members must return:

4. Reach out. Finally, three or four days before the board meeting, each board member should be called and asked if he or she is coming to the meeting and whether the materials sent ahead were clear. For board members who often don’t read anything in advance, specific questions can be asked, such as, “Did the budget report make clear that we are buying a computer over the next year, which means we will be buying it in two fiscal years instead of just one as was recommended at the last meeting?”

These calls should ideally be done by board members. For instance, the chair of the board ought to call anyone who is supposed to give a report at the meeting. As staff, you would call the chair to go over the list of people who should give reports and ask the chair to call them.

Saying to the chairperson, “Sarah, when you call Titus, will you ask him if the stuff about the coalition meeting makes sense to someone who wasn’t at the last board meeting? I’m afraid I may have been too terse,” will cause both Sarah and Titus to read the information about the coalition meeting without ever implying that you thought they might not have done so.

The purpose of this advance work is to show the board that each of their opinions is important and counts with you. Board members are choosing to carry out their responsibilities in a sea of conflicting demands for their time and the time will go to the highest bidder — the person who gives the most back for the time put in. Board members most often don’t do their job because their experience on other boards has been that their work is not valued.

AT THE BOARD MEETING

- Have coffee, tea, cookies, fruit, or other snacks available.

- Hold the board meeting in a reasonably pleasant place that is easy to find. If your office is overcrowded and messy, don’t have your board meeting there. Board members often volunteer to have meetings at their homes, but homes can be hard to find and people then feel that they are a guest in someone’s house rather than a board member at a meeting. In most communities, it should be possible to reserve a neutral assembly space, such as a room in a bank, church, or community center, without charge.

- Have the chair agree to start the meeting on time, even if only two or three board members are there. If the chair is late, ask one of the other board members to step in until the chair arrives. You will only need to do this once to show that board meetings start promptly. Have a similar agreement to end on time.

- Make sure the agenda builds in a short time for people to review material. Even those who have read it in advance may not remember it thoroughly.

- Be sure that everyone knows each other. This is particularly important for boards that meet infrequently, when board members come from far away, or when there are new board members. Spend time greeting people, introducing people again, etc. As each person comes into the room, say, “Hello, [Name],” in a fairly loud voice so that anyone who didn’t remember that person will be reminded of who they are. Always use board members’ names to them and about them, even if your sentence would work without doing that. For example, say “Car-men, how are you?” rather than just “How are you?” or, “I was just saying to Loretta that it hasn’t rained in two weeks,” instead of “I was just saying that it hadn’t rained …” In situations where there are a lot of new people, name tags are important.

- Have an alarm clock or wall clock visible to the whole group so that everyone becomes somewhat conscious of time.

- For meetings that are scheduled to exceed two hours, be sure the agenda builds in 15-minute breaks after every second hour.

- Make sure that the person facilitating the meeting is skilled in basic facilitation techniques. This may mean working with her or him ahead of time to be sure that everything runs smoothly.

- Remember that people are often afraid to ask for clarification of points they may feel they ought to know. For example, at a meeting of a new grassroots organization, a board member did not know the meaning of the 501(c)(3) status that was being discussed. She thought people were talking about Levi’s 501 jeans. As board members debated whether to get “501(c)(3) status” she retreated in puzzlement. Board members can’t be expected to remember every current acronym either. While staff are completely familiar with the BEB Coalition and the SEH Network, along with ASPI, SECU, etc., board members can be lost. Take time for definitions. Do not ask, “Does everyone know what SEIU is?” People who don’t will not be comfortable raising their hands. Simply say, “People will remember that SEIU is the Service Employees International Union and we are working with them on the health care initiative, which we sometimes refer to as PCP.”

- For every major decision, coach the chair to make sure everyone is heard from. The chair should look at each person and ask their opinion: “Rosa, what do you think?” “Gary, we haven’t heard from you.” This technique will ensure that no one feels left out.

- Have a few extra copies of all the materials you sent ahead, but not enough that people think you assumed they would forget them. In a board of 12 people, two extra copies of everything shows that you realize someone’s mail could have gotten lost, but that basically you trust board members to bring their materials.

- Make sure the chair ends the meeting formally. She can say something like, “This meeting is adjourned,” or, “That’s all for today. See you on the 12th,” or, “Thanks for coming and working so hard.” As staff, you can try to say goodbye to everyone individually on their way out.

In summary, board members will generally rise to the occasion. As staff, it is your job to keep creating the occasion.