January 28, 2014; New York Times

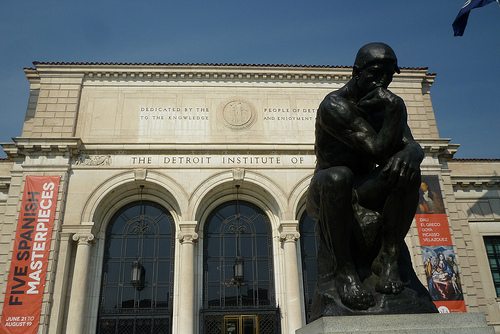

Add $40 million from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to the pledges of nine foundations to save, they contend, the art collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts from being sold off to help fund Detroit’s estimated $3.5 billion unfunded municipal pension liability. With Kellogg in the mix, the foundation pool for the DIA climbs to $370 million.

Governor Rick Snyder has proposed that the state add another $350 million to help with the city’s financial problems, an apparent requirement of the participating foundations, though the state legislature hasn’t yet given a full endorsement to the additional funding. For the foundations, the DIA is an understandable vehicle for philanthropic assistance to the city, in contrast to pledging money directly for the pensions, not typically a philanthropic grantmaking priority.

Although a very large grant, Kellogg’s $40 million is less than the Ford Foundation’s $125 million and the Kresge Foundation’s $100 million contributions to the pool.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The response to the foundations’ intervention in Detroit has been overwhelmingly positive, but recently, a powerful critique was published by the Hudson Institute’s William Schambra in the Chronicle of Philanthropy. Schambra noted that the initiative for the foundation pool came not from the foundations, but, according to Miriam Noland of the Community Foundation of Southeast Michigan, from a call from the federal judge in charge of mediating the Detroit bankruptcy, Gerald Rosen, who suggested that the foundations raise $500 million to help the city out of its predicament. Schambra quotes this writer that the foundation strategy lacks some essential elements of democratic process, having been initiated and negotiated by an unelected judge and unelected foundation executives in a less than transparent manner, with various conditions of the agreement still not revealed to the public.

Another concern raised by Schambra is the precedent the deal sets: a rescue of the city’s pension funds under the guise of saving some of the city’s art collection from potential revenue-generating sales to bail Detroit out of its fiscal predicament. Will other cities with pension issues that dwarf Detroit’s be knocking on the doors of their local foundations? Will Chicago, facing a mammoth pension crisis, send letters to the MacArthur Foundation and the Chicago Community Trust seeking pension fund help?

Our question would concern what happens to the participating foundations’ other grantmaking priorities. Foundations such as Kresge have pledged that their commitment to the DIA/pension pool won’t adversely affect their grantmaking to other Detroit initiatives; for example, Kresge has done groundbreaking and path-laying work to bring economic and community development to Detroit’s ravaged neighborhoods in a completely new way. Unlike the DIA deal, the Detroit Future City Plan, presented by Kresge in conjunction with other foundations, including some in the DIA pool, was developed through hundreds if not thousands of meetings with neighborhood residents and community leaders.

No one here doubts the foundation leaders’ intent to maintain their grantmaking to Detroit’s struggling nonprofit sector and its pledge to fund the initiatives flowing from the Future City Plan and other programs, but a foundation president or CEO isn’t the only decision-maker at a foundation. How will foundation trustees react over the long run as they try to balance their multimillion-dollar commitments to the DIA and pensioners with the continuing demands for local funding? Will some program officers use the deal as a “we gave at the office” kind of answer to local nonprofit grant applicants, essentially using the foundations’ DIA/pension commitment as a neat, all-purpose way of dealing with community-based nonprofits’ expectations and wants?

Kellogg’s grant in some ways is one more example of foundations trying to credibly respond to the overwhelming fiscal needs of Detroit. Attached to saving the Detroit Institute of Arts, the foundations have a vehicle for their intervention in Detroit’s fiscal problems that seems philanthropically legitimate. But the deal is short on transparency and democracy, regardless of the foundations’ sincere motivations, and may come with challenging precedential ramifications in the future both in Detroit and in other cities.—Rick Cohen