May 3, 2016; Washington Post

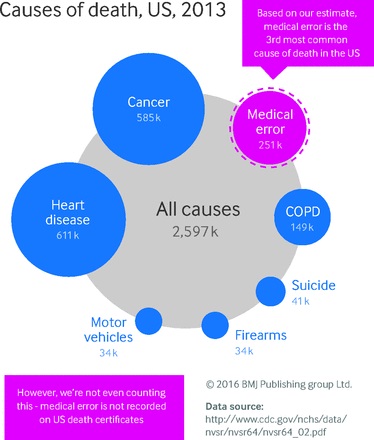

The results of a study released on Wednesday, May 4th, by the BMJ indicate that preventable medical error is the third-highest cause of death in the United States. The number of deaths annually caused by medical error may be as high as 251,000—more than respiratory disease, accidents, stroke, breast cancer, and Alzheimer’s. They comprise, in fact, an estimated 9.5 percent of deaths overall.

Prior to this, the estimated number of annual deaths from medical error was set at between 44,000 and 98,000, using the results of a landmark 1999 study by the Institute of Medicine. But since then, other studies have suggested a figure far higher. This study, published yesterday in the BMJ, reviewed the literature on the topic to come up with a more accurate estimate.

Martin Makary, a professor of surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and an authority on health reform, led the research. “It boils down,” he said, “to people dying from the care that they receive, rather than the disease for which they are seeking care. We all know how common it is. We also know how infrequently it’s openly discussed.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This, Makary says, creates a barrier between consumers and policymakers and the information and the. The U.S. assigns an International Classification of Disease (ICD) code to the cause of death, which excludes the capturing of medical error as causal, resulting in the issue not being cited as a major health concern. This, then, drives research away from what amounts to an epidemic of substandard care.

Kenneth Sands, who directs Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, an affiliate of Harvard Medical School, says there has been limited change since the IOM report came out, and that was in the area of hospital-acquired infections. “The overall numbers haven’t changed, and that’s discouraging and alarming,” he said. In fact, in April 2016, Consumer Reports, which had done an investigation of California licensing records, found many doctors who were still practicing but were on probation for serious violations of patient safety.

“There has just been a higher degree of tolerance for variability in practice than you would see in other industries,” Sands explained. As an example, when passengers board a plane, there’s a standard way attendants move around, talk to them, and prepare them for flight, yet such standardization isn’t seen at hospitals. That, Sands said, makes it tricky to figure out where errors are occurring and how to fix them.

Makary continued with the aviation metaphor, saying that every pilot in the world learns from investigations, but in medicine, they are hidden under lawsuits and gag agreements. “When a plane crashes, we don’t say, ‘this is confidential proprietary information the airline company owns.’ We consider this part of public safety. Hospitals should be held to the same standards.”

The lack of data gathering and sharing is a serious problem, according to Makary. “Measuring the problem is the absolute first step,” he said. “Hospitals are currently investigating deaths where medical error could have been a cause, but they are under-resourced. What we need to do is study patterns nationally.” Sands agreed, saying that government should work with institutions to try to find ways improve on this situation.—Ruth McCambridge