Editors’ note: This article, first published in print during Mar/Apr 2007, has been republished for Nonprofit Quarterly with minor updates.

Fundraising consultant Jean McCord recently shared some reflections with us about her experiences as a donor to nonprofit organizations. We follow with some concrete suggestions for ways to strengthen, rather than harm, your relationships with supporters of your group adapted from an article by Kim Klein, “Practical Ways to Build Relationships with Donors,” published in the Journal in 1997.

Confessions of a Curmudgeonly Giver

By Jean McCord

Like many people, I commit at least some charitable giving at the start of each year, pledging to my church and nonprofits close to my heart. I’ll pay those pledges, no matter what. However, because I’m a consultant, my income is uneven. Some years are particularly good financially, and some not so good.

Several years ago, at the end of my first unexpectedly good year, it was a joy to make additional gifts. My church and “regulars” got extra gifts and I picked 10 other nonprofits to receive either $50 or $100. These weren’t large gifts, but they were from the heart to charities I felt good about. Nine thanked me within 30 days, giving me another burst of joy with their thanks. They also waited a decent interval before asking for more. I’ve since given most of the nine fairly significant amounts.

One $50 recipient did not bother to thank me, but did ask for a gift two months later. I called to be taken off the mailing list and told the director of development why. She said, “We thank people only if they give at least $100.” I’ve sent it nothing further.

Over time my interests changed, and I’ve asked to be permanently removed from some mailing lists. Most charities complied. However, one re-solicits me occasionally, even though I’ve informed it repeatedly that I’m no longer interested and never will be again. Each missive elicits only annoyance and another request to be removed.

More recently, I decided I didn’t want to be on any additional mailing lists. I called one “new” charity, made a $500 year-end gift over the phone, and stressed that the only mail I wanted was an acknowledgment so I could deduct the gift. Further, I did not want any phone calls, e-mail, or other communications. “I know where to find you when I want to,” I said. The charity sent a warm acknowledgment letter and otherwise has left me alone — except for acknowledgments when I’ve sent additional fairly large gifts at irregular intervals. That charity respects me, I respect it, and I’ll continue supporting it — all the way to my estate plans.

In late 2004 I explored giving online for tsunami relief. Since there was no way to express my wishes online, I telephoned the agency’s national office. A nice person took my $500 gift and promised I would receive the acknowledgment and nothing else. However, several months later the local chapter both telephoned and wrote me, asking for “at least” a repeat of the $500 gift. I demanded to be removed. This group continues to hound me, and every time I hear from it, I demand to be removed. Lately they’ve even begun misspelling my name.

Some years ago a friend died in a distant state. Her husband requested memorials to the hospital where she had died. I sent a check with the notation that this was a one-time memorial gift, and used my rubber stamp that says, “Please do not put my name on ANY fax, mail, phone, or e-mail lists.” In case that wasn’t clear enough, I added — in red ink — “not even yours.” Later I received an annual report and solicitation.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

I use another rubber stamp to place the message, “Please take my name off your mailing list,” on the charity’s postage-paid envelopes or I send it via their 800-fax number when responding to unwanted mail. If the postage isn’t paid, I use the 800-phone number to call and ask to have my name removed. I have no qualms about making the charity pay for removal requests after it has ignored my wishes.

My behavior isn’t typical, but it’s not unique, either. Friends have told me they’ve squelched charitable urges to avoid a deluge of mail from the charity they would have given to and subsequent “related” others they’ve never heard of. I believe them — and I know there are many others like them.

The Web makes it easy for people to research charities. Increasingly, some will give based on research rather than on contact from the charity. Some are concerned about the environmental waste of unwanted mail; others are concerned about the time it takes to read postal or e-mail.

If your charity wants gifts from such persons, it must treat them as they ask to be treated — even when it goes against regular fundraising practices. Donors who take the trouble to express their wishes feel strongly about them.

I’ll continue giving when I can to what I want to give to — and I’ll make each gift as large as possible at that time. The timing, recipient, and amount are up to me, not the nonprofit. If I ask to be left alone, I expect my wishes to be followed. Even curmudgeons have rights.

Practical Ways to Build Relationships with Donors

By Kim Klein

Some of the problems Jean describes in dealing with donors are the result of poor systems, missing records, and overworked staff, but some of them are because we haven’t yet made relationship-building with our donors a high enough priority in our work.

Following are some tips for building better relationships with your donors, which will result in more money, more goodwill in the community, and ultimately greater success in fulfilling your organization’s mission.

- Building relationships with donors means giving them opportunities to tell you how and how often they would like to be approached for money. Many people who give money feel more and more besieged by nonprofits. Every day brings a new pile of mail appeals; every evening brings a phone call; every shopping experience includes offers to buy newspapers from the homeless, drop change into canisters for people with AIDS, and buy candy/cookies/crafts from schools or publicly supported radio stations. Recently, a friend opening her mail read a moving appeal on behalf of Siberian tigers who may soon be extinct. She commented to me, “I think givers are also being hunted to extinction.”

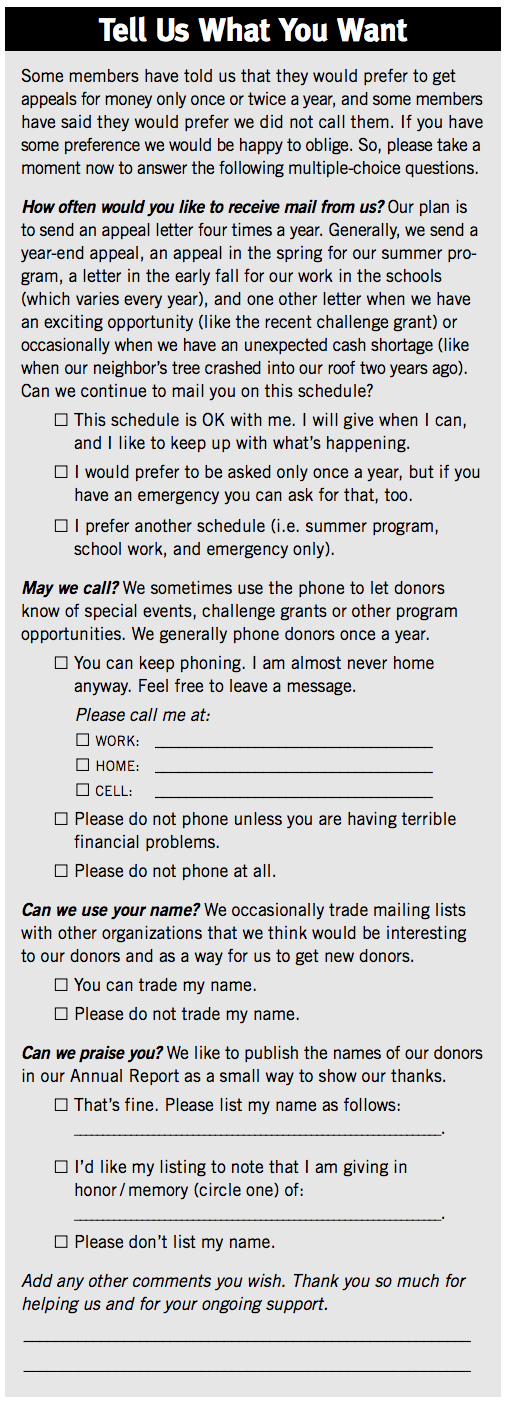

Give your donors a chance to tell you their preferences. For example, for donors whom you relate to only by mail, include a form with your thank you note for them to send back with information about how and how often they would like you to keep in touch with them. But don’t imply that you think they would like to be asked less often or never called. See the box, “Tell Us What You Want,” on the following page, for an example of a questionnaire one group sends to their donors. This group has had good feedback from this system, and reports that 90% of the donors returning this form asked to be kept on the same schedule they were on (four letters and one phone call per year). Many said, “Thanks for asking.” Some requested to be phoned instead of written to, and a handful said the group could ask more often! Donors are all different.

- Heed direct requests from donors. When donors add notes to their checks saying, “Do not phone” or “I only give once a year,” honor that.

- Make thank you notes as personal as possible. The best way to do this is to add a personal, hand-written note on the computer-generated thank you letter. In addition, if the gift was solicited by someone other than the person signing the thank you note (say, a board member), have them send a separate, hand-written thank you.

- When a donor makes an unusual gift, call to thank them. For example, a donor giving $25 a year for two years starts pledging $15 by EFT, or a donor who gave $100 a month ago sent another $50 in response to a newsletter appeal. The call is in addition to the written note, of course.

- Visit your best donors. Someone from your board, fundraising committee and staff should try to see as many of the top 10% of your donors as possible—in person—to ask for their gift, or to upgrade their gift, every year or two. When you visit with a donor for even 20 minutes, you learn more about them and what they like and don’t like than you will through years of notes or phone calls.

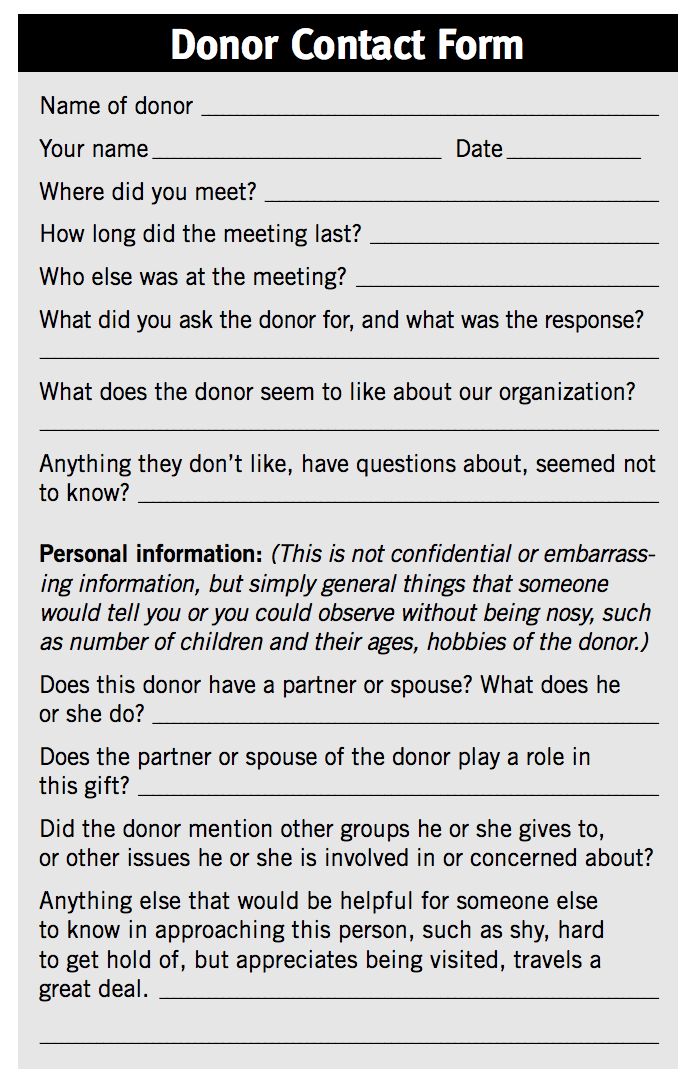

- Keep written records of donor visits. Give solicitors a form such as the “Donor Contact Form,” on following page, to be filled out after each visit. The form has a few questions to prompt their memory. Then enter this information into your database and store a copy in the donor’s file. The next time someone is trying to get an appointment with this donor, you’ll have the history of that donor’s giving, as well as information about their relationship with your group that will help make the next visit go smoothly.

- Review your donors. Once a year (or more often if you can) bring together a small group of board members, key volunteers, founders of your organization — in other words, people who tend to know the people who give to your group — and have them review the list of your donors and their giving amounts. Ask them to note who might give more, who might be a good board member, who might open doors to other donors, who might be willing to volunteer for a specific task, and so on. As they go through, jot down any important or useful information that comes up, such as the birth of a baby, death of a close relative, or move to a new home. Later, if you wish and it feels appropriate, send a note of congratulations, sympathy or whatever the event calls for.

An organization needs to see its donors as the equivalent of family and friends — they take time, they have their idiosyncrasies, some of them are very different from you, but they are worth getting to know because their gifts — money, time, connections, advice — make