Nonprofits have a significant stake in the deal cut between the Obama Administration, 49 states, and the five largest mortgage servicers in the wake of the mortgage crisis. JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citigroup, and Ally Financial will pay $25 billion as a legal settlement to release them from federal and state (excepting Oklahoma, which negotiated its own settlement) claims regarding the banks’ failure to help borrowers before foreclosure, their “robo-signing” of mortgage foreclosure documents, and other highly criticized bank practices. The agreement calls for the banks to stop those practices in the future.

Now, lots of people are fighting over whether these banks got off cheap or are paying what they justly deserve to pay, whether the governments’ settling with them will adversely affect individuals’ claims against the banks (even though the settlement does not preclude individual actions against the servicers), and whether the settlement will somehow propel the housing market out of its doldrums.

The market impacts of the deal are a matter for the economists to debate, but what is the upshot of the mortgage settlement for the nonprofit sector?

First, the facts about the settlement distribution:

- The $25 billion will be distributed over a three-year period, not all at once. The settlement includes incentive provisions to get the banks to speed up the money in the first year, however. Like most settlements, we know that there are significant problems with monitoring and enforcement from the governmental end. That is all but assured. In this case, we suspect that the array of highly motivated and capable nonprofit advocates in the banking realm, such as the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, the Center for Responsible Lending, and others will be painstakingly attentive to ensure that the settlement terms are met.

- $1.5 billion will go to borrowers who lost their homes after January 1, 2008, but is restricted to borrowers who can show that they were not properly dealt with in the foreclosure process—that is, those who were either not offered appropriate opportunities for loss mitigation or were otherwise victims of improper foreclosure processes. The result is an estimated $2,000 payment to each eligible foreclosed homeowner.

- The settlement makes $17 billion available for principal reduction and other modifications of existing mortgages to prevent future foreclosures, and three-fifths of the sum must be used for principal reduction, the aspect of foreclosure prevention that the banks have most stridently opposed due to their investors’ protests and the securitized mortgages they’ve sold to Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and on the stock market. This provision looks a little odd, since it seems that the banks can get credit for the principal reductions they offer rather than having to pay toward the actual settlement penalty. This will likely result in another oversight and monitoring issue.

- Another $3 billion will be used to refinance the mortgages of borrowers who are “underwater,” meaning their mortgage loans are larger than the current value of their properties.

These are the direct homeowner assistance provisions, but there are also issues of more direct concern to nonprofits in terms of their functions in this deal, which we outline below.

Who Pays for Housing Counseling?

The settlement includes $2.5 billion—and potentially as much as $2.66 billion—for state-level anti-foreclosure initiatives, which typically include housing counseling. This might be a three-year boost to the nation’s nonprofit housing counseling industry. The important successes of nonprofit housing counselors (in the face of bank intransigence and a lackluster federal approach to the banks) have been undone in recent years by the failure of Congress to appropriate housing counseling moneys in the federal budget. The minimal dollars in the budget for pre- and post-purchase counseling, as well as mortgage foreclosure counseling from organizations such as NeighborWorks, has been telling. This is especially true given the success of NeighborWorks in taking a Congressional mandate for foreclosure counseling during the Bush administration—entirely bypassing the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)—and distributing funds to local nonprofit counseling agencies around the nation in a rapid timeframe (see here and here). Since then, however, counseling money has been hard to find, though the Obama administration’s HUD had backfilled counseling funds by redirecting community housing development organization (CHDO) capacity-building and training funds for housing counseling, among other strategies. Without nonprofit counseling services available as alternatives to the for-profits that have preyed on desperate homeowners, one can imagine more homeowners losing their homes to foreclosure—and perhaps losing much more by delivering payments they don’t need to make to purported counselors whose objectives may be at odds with those of homeowners.

Still, does this provision represent a trend of government looking to settlements to pay for functions that should be addressed by regular government appropriations and domestic spending? The nonprofit sector may be compelled to latch onto these moneys through the states, but at the same time, they may wish to step up their advocacy for government to return to its role of providing direct funding support for critical elements of the safety net rather than relying on the happenstance of events such as legal settlements to act as a stand-in for the appropriations process.

Who Stops Funding Diversions?

With state budgets in miserable shape, one would have little trouble predicting that some states may seek to use mortgage settlement funds for unintended purposes. For instance, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker quickly floated the idea of taking $25.6 million from its $140 million share of the mortgage settlement to address its deficit. And Missouri is aiming to use $40 or $41 million from its $155 million share to reduce scheduled state budget cuts to higher education.

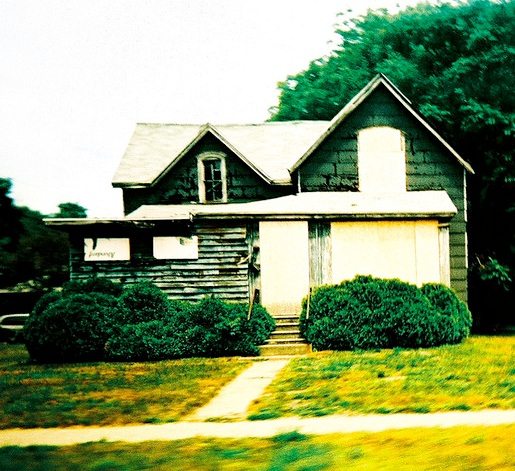

Anyone who has monitored some state government uses of the tobacco settlement funds knows how desperately states will try to repurpose this “free” money. In some cases, they might try to maintain something of a tenuous link to the intended purpose of the funds. For example, Ohio plans to use some of the moneys not for counseling or legal assistance to homeowners, but to demolish vacant properties. Since Cleveland and other cities have such an overflow of vacant buildings, it is an understandable strategy. In cities with continuing foreclosure dynamics, predators monitor foreclosure lists and tax sales, monitor when people move out, and within what appears to be milliseconds, invade the foreclosed homes, stripping them of pipes, wiring, appliances, and anything of value.

Gov. Walker in Wisconsin and Gov. Jay Nixon in Missouri have already sparked a big pushback, including a new bill in the Wisconsin legislature to stop Walker’s planned diversion of the settlement funds. Walker is a national target due to the impending recall election he faces, but the reality is that all states with red ink in their budgets may look at these settlement funds with a hungry eye to fill budget gaps. If the mortgage settlement is to be used as intended, it is critically important that some semblance of a nonprofit infrastructure in the 49 states is prepared to fight to protect these funds, which should go to and through nonprofit delivery systems.

Who Will Help Neighborhoods Devastated by Foreclosures?

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The Ohio plan for demolitions points out one of the saddest corollaries of the past five or six years of the national mortgage meltdown. Many of the neighborhoods that nonprofit community development corporations and nonprofit housing developers have worked for decades to turn around and revive have slid backwards. In some, low homeownership rates and high vacancy rates are back to their dismal pre-redevelopment levels. For many, it’s back to the starting gate. The neighborhood redevelopment and revitalization process has to start all over again, not due to the inadequacies of the nonprofit community development sector, but because of a mortgage crisis that was due to big bank practices completely outside of the sector’s control.

The settlement calls for the banks to participate in state and local programs to combat blight. The range of programs referenced include land banks and nonprofit neighborhood revitalization programs, plus admonitions that banks cannot be permitted to simply walk away from properties (by failing to see the foreclosure process through to completion) or leave foreclosed properties as unsecured and unprotected homes to be trashed by thieves and speculators. But where is the money for this? Given the millions of foreclosures that have already happened and the still-burgeoning foreclosure dynamics in many cities, the numbers are staggering—both in terms of the ability of local markets to absorb units and the capacity of nonprofit redevelopers to acquire and rehabilitate units. It would have been entirely appropriate for the settlement agreement to create an additional pool of funds for nonprofit capacity building, for predevelopment and construction loans, for acquisitions, and more to help make anti-blight efforts conducted by the nonprofit sector actually work.

Given that the housing market is still slow, due to both banks’ financing reluctance and because of potential purchasers own economic challenges (remember the numbers of unemployed and underemployed), the likelihood is that a large piece of the redeveloped properties will end up as renter-occupied. Is it beyond the ken of our nation’s settlement negotiators to understand that scattered-site rental projects are a management nightmare? They are hugely expensive and difficult.

For nonprofits that care about the conditions of neighborhoods and the welfare of their occupants, these rental projects are generally non-starters. Many nonprofits that used to do scattered-site management simply don’t any longer. The money just isn’t there to make it viable—except for the for-profit speculators who will come in, acquire a bunch of foreclosed properties in bulk, and milk the properties and their occupants dry before they ditch them. If the anti-blight efforts are going to work, state and federal agencies are going to have to come to grips with the costs and challenges in managing scattered-site rentals. Otherwise, the nation will see continuing, cascading problems in neighborhoods.

Who Is Going to Talk to Fannie and Freddie?

The settlement directs $1 billion to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development for its Federal Housing Administration (FHA) capital reserve funds, which is another source of lending with a stock of lower income homeowners facing foreclosure. But where are the inventories of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in this process? They control huge inventories of mortgages, many no less troubled than the banks and with large percentages “underwater.” Why aren’t Fannie and Freddie part of this deal?

The answer, it seems, is because the government regulator in charge of overseeing the two elephantine government-supported enterprises is dead set against the concept of principal reduction and no one in the White House or Congress appears willing or able to convince him otherwise.

Perhaps the White House and the state attorneys general decided it was best to approach the problem piecemeal, in large but still digestible pieces, taking on the five big banks first, and then dealing with Fannie and Freddie later. But the big banks, all of which received huge taxpayer subsidies through TARP, have paid back their moneys—making TARP one the nation’s rare examples of taxpayers making a profit from a governmental intervention in the economy. Meanwhile, taxpayers still largely own Fannie and Freddie due to their need for large and continuing bailouts, and the acting head of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, Edward DeMarco, is intent on maximizing the nation’s potential return on its investment by protecting the principal value of Fannie and Freddie mortgage assets rather than adjusting to the reality of principal reduction. Because of the exclusion of Fannie and Freddie from the deal, homeowners with mortgages owned by these two government-supported lenders are left without access to the help that will be afforded to homeowners with mortgages made or serviced by the five banks. The sheer inequity of this arrangement is somewhat staggering, both for homeowners and for communities.

Who Isn’t Helped?

What does it all add up to? Estimates are that the settlement may help as many as 1 million homeowners—but 11 million homeowners sit with mortgages underwater. As two Milwaukee advocates put it, “the $17 billion for principal reduction and refinancing is a drop in the bucket of the estimated $700 billion negative equity in which homeowners and the economy are currently drowning.” While the five banks in the settlement are huge, the settlement doesn’t help half of the nation’s homeowners, those whose mortgages are held by other banks, by Fannie and Freddie, or by the FHA. For instance, in California, only 40 percent of statewide mortgages come from the five banks.

Even with incentives to step on the gas, one can be assured that the banks may not be quite ready to peel out onto the road. The banks have known the contours of the deal for months, but calls to the major banks reveal that they haven’t started thinking about how they plan to distribute the assistance called for in the settlement. The bulk of the funds will go to homeowners in Florida and California, where the most troubled homeowners reside, but many people will be left without assistance.

Critics are concerned that this is hardly a slap on the wrist for the five banks. Per the settlement, Bank of America will be paying $8.6 billion, Wells Fargo $4.3 billion, JP Morgan Chase $4.2 billion, Citigroup $1.8 billion, and Ally Financial (formerly GMAC) $200 million. These are big numbers, but in some ways, they are small potatoes to banks that have been enjoying astoundingly positive returns since they were given the breath of life by the TARP bailout. To the banks, those sums are similar to what one critic called the $2,000 restitution payments: “chump change”.

Critics are also concerned that this deal will lead to more foreclosures, or at least a more rapid rate of foreclosures. While the settlement was in the works, banks slowed the pace of foreclosures down to see what they would be required to do regarding principal reduction. Now that the deal has been struck, the banks will restart the mortgage process again, probably adding to the inventory of foreclosed properties and pushing home prices down. Will that jump start the housing markets or further depress them?

Based upon the settlement’s inadequacies, as described above, there is a huge need for the nonprofit sector to gear up its organizing and advocacy more than ever. No one should sniff at $25 billion in assistance, including over $2.5 billion that could potentially reach nonprofit housing counseling organizations. But the battle to turn this settlement into more than legal chump change for the housing markets and for the nation’s dispossessed homeowners is nowhere near over.