This article is from the Nonprofit Quarterly’s spring 2018 edition, “Dynamics and Domains: Networked Governance in Civic Space.”

Over the last decade, the Internet and social media have radically changed the nature of charitable fundraising. Today, even the smallest local charity can raise or receive funds from individuals all over the country and the world. Donations are often made through websites, social media platforms, mobile apps, and an ever-growing array of peer-to-peer and other online fundraising platforms and technologies.

I am frequently asked whether and to what extent these online fundraising activities trigger state charitable fundraising registration and related compliance obligations. The inquiries come from all types of organizations: local, regional, national, and international; public charities and private foundations; start-up businesses and publicly traded companies; and entities formed in the United States and in foreign countries.

The one thing they all have in common is that they are conducting fundraising activities on the Internet and realize that there could be multistate regulatory implications. For entities that are already registered nationally, the question is whether specific contractual relationships are subject to the laws of the various states (including registration, filing, contract language, and disclosure obligations) when fundraising activities will be conducted online only.

Online fundraising compliance has been written about frequently. Most articles seem to lead readers to one rather simplistic recommendation: Register nationally if you fundraise online. The argument is usually presented as follows: Once a charity has received an online donation from a resident of a state, any follow-up solicitation to that donor constitutes soliciting in that donor’s state. In order to solicit in the donor’s state, the organization must register there. Under the assumption that the charity would want to solicit that person again, the advice is that the organization should just register. This one-size-fits-all recommendation makes a bold supposition that an organization wants to send follow-up solicitations to anyone who has donated online from any state. However, here are some alternate hypothetical scenarios that may warrant another approach:

- A youth charity based in Boston provides educational programs to children from low-income families. The charity has a website, including a donation page, through which it primarily receives donations from Massachusetts residents. It occasionally receives donations from residents of other states, but typically they are small in dollar amount and few in number (e.g., three online donations per year and $150 total from New York residents). The charity sends its out-of-state supporters a donation tax receipt by e-mail but otherwise does not send any solicitations to these donors.

- A start-up T-shirt company located in Vermont has created a special custom-designed T-shirt made from recycled plastic bottles. The company has produced two thousand limited-edition T-shirts to be sold at $20 each, and advertises on its website that it will donate 20 percent of the sales price from each T-shirt sold on its website to a national environmental-awareness charity. If all of the T-shirts are sold, the company will donate $8,000 to the charity.

Many online fundraising activities in which there is a limited nexus between the charity/fundraiser/company and the state whose regulatory jurisdiction is in question exhibit several or all of the following characteristics:

- The opportunity to donate or make a purchase that benefits a charity is only available online.

- Only a small number of donations (or sales transactions leading to donations) are generated (or likely to be generated) from the state.

- The fundraising activities are short term.

- The charity has no plans to actively target residents of that state now or in the foreseeable future.

- The charity’s role is largely passive (this is particularly the case with peer-to-peer fundraising activities and charitable sales promotions).

Charitable fundraising is no longer just a top-down activity initiated by the nonprofit. In fact, opportunities to benefit from ad hoc fundraising activities are being presented to charities by businesses, technology companies, and individual supporters at an unprecedented rate. As such, it is imperative that charities establish a clear compliance strategy to manage the barrage of fundraising opportunities coming their way.

Regulatory Framework

In outlining the regulatory framework for online charitable fundraising, I will review the current status of Internet charitable fundraising regulations, discuss the underlying constitutional and policy concerns with various regulatory approaches, and then outline a systematic approach that organizations can follow to evaluate their compliance obligations on an ongoing basis.

In order to understand the current status of online charitable fundraising regulation, it’s helpful to take a quick trip back in time to October 1999. Internet fundraising was in its infancy when members of the National Association of State Charities Officials (NASCO) and the National Association of Attorneys General (NAAG) met in Charleston, South Carolina, and agreed to adopt a set of principles to clarify how state charitable solicitation regulations apply to Internet fundraising. Two years later, in March 2001, The Charleston Principles: Guidelines on Charitable Solicitations Using the Internet (the Principles) was published. The principles are not binding laws but rather advisory guidelines for state charity officials to consider in applying their charitable solicitation statutes to Internet-based fundraising activities.

The Principles asserts that existing registration statutes apply to Internet solicitation. What does that mean exactly? As an example, let’s take a look at section 172 of the New York Executive Law, which states that “Every charitable organization…[with certain exceptions] which intends to solicit contributions from persons in this state…shall, prior to any solicitation, [file with the attorney general]….”1 If a local organization in Utah puts a “donate” button on its website or hosts a crowdfunding campaign on a third-party fundraising platform’s website, for instance, does the charity “intend” to solicit contributions from persons in New York? The principles were established to help regulators apply existing laws to this new frontier of fundraising by defining and limiting the circumstances in which a nonprofit must register with a given state based on its online fundraising activities. According to the Principles, state registration and reporting regimes apply to Internet solicitations in the following three circumstances:

- The “entity is domiciled within the state….”2

If an organization is soliciting online—that is, it has put up a “donate” button on its website or Facebook page—the organization will be considered to be soliciting in its state of domicile. It is likely that most organizations have registered to solicit in their state of domicile because of their non-Internet fundraising activities (e.g., local, in-person fundraising events or direct-mail solicitations). However, this prong may be newly relevant to one group of organizations—private foundations, which typically do not solicit contributions because they are generally funded by one or a limited number of donors. Increasingly, many private foundations are becoming interested in adding a donation feature to their websites. This is often their first public solicitation activity and would trigger registration in their state of domicile (if the state requires registration to solicit, as most states do).

- An out-of-state entity that “solicits through an interactive Web site; and…specifically targets persons physically located in the state”3

If an organization is conducting state-targeted solicitation activities in conjunction with its Internet solicitations, it will need to register in that targeted state. An example of this might be an online charitable sales promotion in which a company advertises through its print brochures—which are mailed into all fifty states—that 10 percent of all sales made through its website during a given month will be donated to a designated charity. This type of promotional activity would subject the promotion to registration and compliance obligations in all applicable states, even though the actual sales transactions only take place online.

The requirement that an out-of-state entity specifically target persons physically located in the state also raises questions when applied to e-mails. According to the Principles, a person will be “specifically” targeted if the sender knows, or reasonably should know, the recipient is “physically located in the state.”4 Although e-mail addresses do not generally include geographic identifiers, the Principles suggests that there are ways an entity reasonably should know where an e-mail is being directed—for example, if the e-mail address is linked to a physical address as a result of a prior credit card transaction.

- An out-of-state entity that solicits through an interactive website and “[r]eceives contributions from the state on a repeated and ongoing basis or a substantial basis through” or in response to the website solicitation5

Most organizations get stuck on this third prong because the Principles does not define with any specificity the terms repeated and ongoing (referring to the number of separate contributions) and substantial (referring to the total dollar amount of contributions).

The “Annotations to the Principles” section of the document recognizes that for the principles to be useful, “states must draw a bright line, even if that line is somewhat arbitrary and even if it is not the same in all states.”6 In 2006, I cowrote an article arguing that these bright lines are especially important for out-of-state charities soliciting contributions through a website whose contacts with most states is minimal.7 More than a decade later, we still have very little concrete guidance on this point, and organizations and their fundraising partners are left wondering and worrying about whether they’ve crossed the line.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

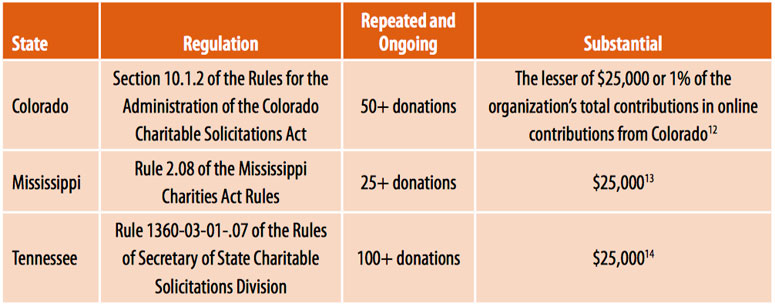

To date, only three states have adopted rules or regulations with specific numerical thresholds for applying the “repeated and ongoing” or “substantial” concepts.8 Their approach to the third prong of the Principles involves analyzing three specific data points:

- Number of online donations received from a state in a fiscal year;

- Total online donations received (in dollars) from a state in a fiscal year; and

- Percentage of total contributions comprising the online contributions from a state in a fiscal year.

The chart below indicates the three states that have issued regulations defining online donation thresholds. In addition to these three state-specific requirements, the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection’s website includes the following declaration: “The State of Connecticut has not legislatively adopted the Charleston Principles, but we do abide by them.”9

Where does that leave the remaining forty-six states? While many have not clarified their positions in any way, some have verbally communicated their approaches to certain organizations but have not otherwise provided public written clarification, passed legislation, or adopted regulations. Alarmingly, a few have taken an extremely broad view of their regulatory jurisdiction, including that a charity is required to register in its state if just one resident donates through its website or if residents of its state simply have the ability to donate through its website, regardless of whether any donations are received from that state’s residents or any targeted solicitations have taken place. Such a broad jurisdictional position could significantly harm smaller organizations within the charitable sector, and—for entities of all sizes—ignores the realities of the borderless world created by the Internet.

The Principles acknowledges that a charitable organization needs to have “sufficient minimum contacts with the state to require registration” in that state.10 The minimum-contacts standard is a constitutional requirement that protects one’s right to due process. The Supreme Court has repeatedly reaffirmed that it is unfair for a court to assert jurisdiction over a party unless that party’s contacts with the state in which that court sits are such that the party “should reasonably anticipate being haled into court” in that state.11 Similarly, minimum contacts are required for a regulatory agency to impose its regulations on a charitable organization or fundraiser. It is worth noting that the “Annotations to the Principles” warns that, “If states assert jurisdiction to require registration under circumstances in which constitutional principles clearly preclude that jurisdiction, then we risk negative court rulings, pre-emptive federal legislation, or both.”

Let’s not forget that the Principles also notes that states can still enforce their laws against “deceptive charitable solicitations, including fraud and misuse of charitable contributions” on organizations that are not required to register in the state.15

What Now? Developing an Informed Online Fundraising Compliance Strategy

Here are some key considerations and steps that organizations can take to formulate and carry out a strategic compliance plan:

1. Be aware of all of the organization’s (and its fundraisers’) fundraising activities. Examine all affirmative, state-targeted solicitation activities (e.g., in-person, direct mail, television, radio), as well as Internet fundraising activities. Charities should also take account of the activities of their fundraisers—paid or voluntary—as well as the marketing activities of their corporate supporters conducting charitable sales promotions to benefit the charity. Development staff should have basic familiarity with the regulatory framework in order to be able to identify when a fundraising activity may trigger compliance obligations, and should discuss any unclear scenarios with the organization’s legal counsel.

2. Track online donations on a periodic basis. In light of the “repeated and ongoing or substantial” prong of the Principles, it is increasingly important for organizations to monitor how much they are generating in donations online, and from whom.16 This information should be reviewed periodically, so that when the appropriate thresholds are met the organization can promptly take steps to register or file appropriate contracts. For the time being, the numerical thresholds issued by the three states serve as formal guidelines for Internet fundraising activities in those states, and may be helpful as informal points of reference for fundraising activities in states that have not provided guidance.

3. Understand the full obligations that come with registration and contract filing. It may seem a simple solution for a charity to decide it will register everywhere “to be safe,” and perhaps the Single Portal Initiative will make that more time- and cost-efficient down the line, but it’s important to understand that registration often triggers one or more related compliance obligations in certain states.17

Those include:

- Qualifying to do business;

- Obtaining a registered agent;

- Submission of audited financial statements (note that an audit costs thousands of dollars, a significant expense for small charities);

- Prefiling of contracts with commercial co-venturers;

- Special contract provisions; and

- Specific disclosures in all solicitation materials.

Most states assess an annual registration filing fee, and once registered, the process will need to be repeated every year unless or until the organization withdraws or closes its registration.

4. Ensure that every fundraising contract is separately analyzed, and that there is a coordinated understanding of applicable state compliance obligations. One way that smaller or newer charities can get into trouble is by being the beneficiary of a charitable sales promotion and failing to register while the company conducting the promotion is submitting the contract to the applicable states.18 This could result in a deficiency notice being issued to the unregistered charity for soliciting (by participating in a charitable sales promotion in the state) without being registered. Similarly, businesses conducting charitable sales promotions can get into trouble when charities disclose that they acted as a fundraiser or commercial co-venturer for them in a particular state, and the company failed to register there.

…

Charities should make sure that each professional fundraiser, fundraising counsel, and commercial co-venturer with which it is working understands where the charity intends to disclose its contract, as well as where the co-venture needs to be registered and/or file contracts and campaign reports because of its fundraising activities for the charity. Do not assume that a general statement in a fundraising contract, such as “Each party agrees to comply with all applicable laws and regulations,” provides sufficient protection. Experience shows that the parties often do not have a shared understanding of the applicable laws and regulations. In light of the rapid growth in online fundraising opportunities driven by technological innovation, it is imperative that nonprofits and their fundraisers understand how the current charitable solicitation regulatory framework applies to their online fundraising activities, and put in place appropriate steps to systematically evaluate those activities and carry out any related compliance obligations.

Admitted to the New York State Bar only. District of Columbia practice supervised by D.C. Bar member Anthony P. Bisceglie, Bisceglie & Walsh, during pendency of D.C. Bar admissions application.

Notes

- The New York State Senate, Executive Article 7-A, Section 172, accessed January 17, 2018.

- “An entity is domiciled within a particular state if its principal place of business is in that state.” In The Charleston Principles: Guidelines on Charitable Solicitations Using the Internet: Final—Approved by NASCO Board as advisory guidelines, National Association of State Charities Officials, March 14, 2001, 3.

- The Charleston Principles, 17. The Charleston Principles discusses a distinction between interactive and noninteractive websites. This distinction is largely moot today, because virtually all organizations soliciting contributions have, at a minimum, a “donate” button on their website, which is an interactive feature. The “non-interactive” option was included when the Principles was written back in 2001, when many websites were not yet interactive.

- Ibid., 18.

- Ibid., 3.

- Ibid., 13.

- Seth Perlman and Karen I. (Chang) Wu, “Legal Fundraising in Cyberspace: The Current State of Internet Law, Fundraising, and Revenue Generation,” NonProfit Times 20, no. 12, June 15, 2006.

- The Charleston Principles, 3.

- “Frequently Asked Questions from Charitable Organizations and Paid Solicitors,” Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection, Sections 21a-175 through 21a-190l, Connecticut General Statutes, last modified March 24, 2015.

- The Charleston Principles, 16. The constitutional standard of “minimum contacts” sets forth the minimum amount of contacts necessary for a state to exercise jurisdiction over a person or entity.

- World-Wide Volkswagen Corp. v. Woodson, 444 U.S. 286, 297 (1980).

- Secretary of State, Rules for the Administration of the Colorado Charitable Solicitations Act [8 CCR 1505-9], Section 10.1.2, November 9, 2012, 12.

- “Rule 2.08 Determination of Online Solicitation,” Mississippi Charities Act Rules: Promulgated Pursuant to the Mississippi Charitable Solicitations Act, updated April 2017, Delbert Hosemann, Secretary of State, 8.

- “1360-03-01-.07: Application of Registration Requirements to Internet Solicitation,” Rules of Secretary of State Charitable Solicitations Division: Chapter 1360-03-01: Regulation of the Solicitation of Funds for Charitable Purposes, March 2009, 2.

- The Charleston Principles, 8, 1.

- Ibid., 11.

- Single Portal Multistate Charities Registration: A NASCO Public Interest Initiative for Information Sharing and Data Transparency, September 2015.

- A “charitable sales promotion” refers to a promotion conducted by a for-profit company in which it advertises that a portion of the purchase price from goods or services sold will be donated to a named charity. Companies conducting these promotions are referred to as “commercial co-venturers.”