This article comes from the summer 2018 issue of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “Nonprofits as Engines of a More Equitable Economy.”

Nonprofit organizations operate in dynamic and lively communities with shifting political landscapes, funder priorities, constituent needs, and demographics. For many for-profit businesses, the direct relationship with their customers creates a feedback system allowing them to understand the impact these changes will have on their business model. But for many nonprofits, those providing the financial capital are different from those using their services—leading to at best a lag in information and at worst misinformation or unaligned forces. John Carver calls this a “muted market” because of the lack of direct voice from those using services.1 The result is additional complexity for leadership in understanding and analyzing the influences the community has on an organization’s business model.

This complexity often leads boards and staff to focus solely on funders when assessing their market in search of sustainable funding. This approach may answer the questions “Where can we sell our idea?” or “What do funders want us to do?” but leaves out the crucial voice of those directly receiving services or benefiting from the organization’s programs. It also doesn’t build the support and engagement necessary for success. Rather, nonprofits need a structured way of understanding the market in their community to inform a different, more important question: “What does our community need us to do?”

Answering this question requires engaging and listening to the broader community. A deeper understanding of the needs and values of different segments of a community strengthens program design, leading to greater impact; and greater impact, together with knowing the values and motivations of current and potential funders, may open up new revenue strategies to increase sustainability.

At Spectrum Nonprofit Services, our previous work has focused on helping organizations visualize their business model using a tool called the matrix map, which showcases how mission-specific and fund-development programs work together to achieve exceptional impact in a financially viable manner.2 This snapshot of an organization’s portfolio of programs allows leaders to make strategic decisions to strengthen the business model. However, just as a boat moving through water is affected by the current, tides, and wind, an organization’s business model is buffeted by external forces that must be taken into consideration for a sustainable strategy.

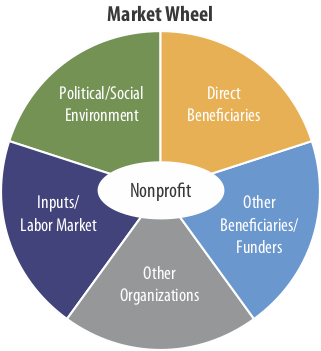

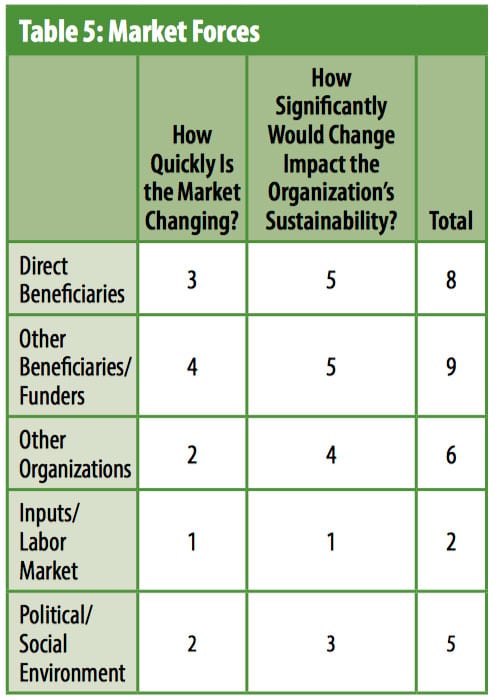

A holistic view of a nonprofit’s market recognizes those who receive services or who benefit directly from an organization’s efforts as well as those who fund the efforts or benefit from the improvement to the community and society. Beyond these two, a nonprofit’s market also consists of other for-profit, nonprofit, and public organizations working side by side, including those whose approaches differ and who compete with the organization for resources, talent, and impact. Likewise, an organization’s mix of programs, effectiveness, and sustainability can be influenced by the availability of skilled labor and by the political and social environment. A true market analysis needs to explore all of these influences at some level. To capture the influences, we segregate the nonprofit market into five components (as depicted in the “market wheel,” above).

- Direct Beneficiaries. The primary pool of people using the organization’s services or directly benefiting from the organization’s efforts.

- Other Beneficiaries/Funders. Beyond their direct beneficiaries, nonprofit organizations benefit multiple other groups by furthering their ideals, values, or shared beliefs, supporting their businesses and complementing efforts in a systemic way. Drawing on Dennis Young’s work on benefits theory,3 this component looks beyond the traditional beneficiaries to include any group of the population that may benefit from an organization’s efforts.

- Other Organizations. No organization operates alone in a community. This component of the market examines other organizations, both for-profit and nonprofit, that share the community. Other organizations may be competitors, or potential collaborators, or—depending on the programs offered—both.

- Inputs/Labor Market. Providing effective services or benefits for the community requires a pool of qualified, talented, and compassionate individuals. Nonprofits compete for human capital every day in the form of staff, volunteers, and board members. Understanding the trends of talent and other resources is essential to having a complete picture of the nonprofit market.

- Political/Social Environment. Nonprofit organizations and those that fund their missions don’t operate in a vacuum. Philanthropic and public funding are both subject to social and political trends that can dramatically influence an organization’s ability to accomplish its mission. Therefore, understanding and working to shape the environment is essential to knowing how to craft an organization’s strategy.

Each of these market components influences aspects of an organization and its business model differently, with some at times being more important than others. From the perspective of delivering exceptional impact, however, no voice is more important than that of the direct beneficiary. Understanding deeply the needs and options of an organization’s direct beneficiaries allows leadership to design both an impact strategy (theory of change) and programs to meet those needs. It also allows the board and staff to understand how the other market components interact with those needs and influence the organization’s business model as it strives to meet them.

The following pages explore each aspect of the market in more detail, and offer a framework for conducting a market analysis that considers each component by asking questions and gathering information to better understand how it is changing. And, recognizing that the depth of understanding of each market component is endless and can be all consuming, they introduce a tool to help leaders prioritize which market forces require immediate strategic attention. Through this analysis, nonprofit leaders, board, and staff together will be able to assess the elements collectively and paint a complete picture of their nonprofit’s market. Then, using the internal assessment, they can engage in discussion and decision making about strategic priorities and how best to structure the operations of the organization to achieve impact and strengthen sustainability.

Direct Beneficiaries

To understand an organization’s market, leadership must start by engaging with (and understanding better) those constituents who benefit directly from the organization’s efforts. For social service organizations, these may be clients; for arts organizations, they may be audience members; for advocacy organizations, they may be those they advocate for; and for some organizations, they may be all three.

While the efforts of nonprofits often benefit many segments of the community, narrowing down those that benefit most directly from the organization’s activities gives leadership increased clarity on and power to navigate their market. Direct beneficiaries can be defined by:

- Age or demographics;

- Socioeconomic status;

- Geography;

- Specific needs; or

- Other distinguishing characteristics.

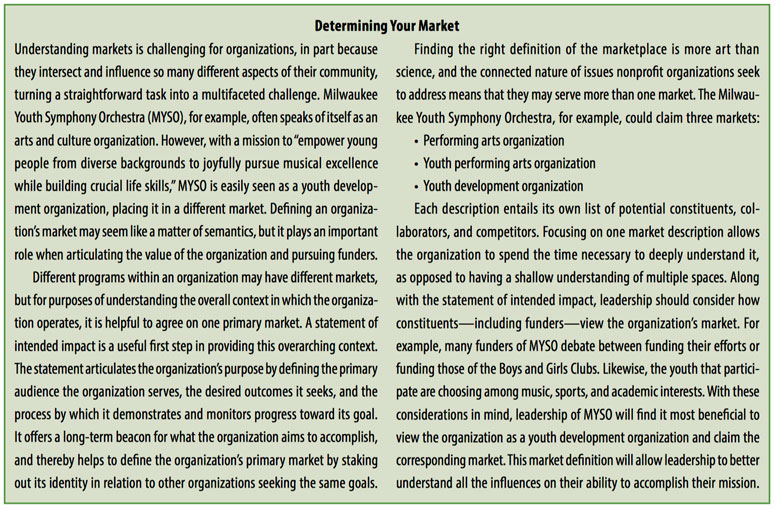

Many organizations struggle with identifying just one group on which to focus. The statement of intended impact—a specific statement identifying the change the organization seeks to create, who the organization serves, and how progress is demonstrated—may be useful here, since that process typically defines a target beneficiary of the organization’s desired impact. Another way to consider direct beneficiaries is to think of groups in concentric circles, with a specific group in the middle (see graphic, above). The innermost circle reflects constituents who are core to the organization—individuals who would either benefit most from the organization’s services or those whom the organization most wishes to serve. Answering the question “Who must the organization serve to accomplish its mission?” helps identify the core direct beneficiary in the center circle.

Moving outward, the other circles reflect groups also benefiting from the organization’s efforts, but less directly. Identifying distinct subgroups of the market in this manner acknowledges that different groups that benefit from the organization may have different needs, and that, at times, trying to reach and satisfy the entire range of different needs is difficult. Concentric circles enable prioritization, which proves useful in setting strategy after the completion of the market analysis.

Some organizations find the concentric circle prioritization challenging, as they have multiple subgroups of direct beneficiaries that are equally served by the organization’s efforts. In these cases, a table of two to four subgroups with equal weight can be created. Larger organizations with multiple programs, for example, may find that their programs have distinct core beneficiaries. To truly understand the influence of this market component, all direct beneficiaries need to be understood.

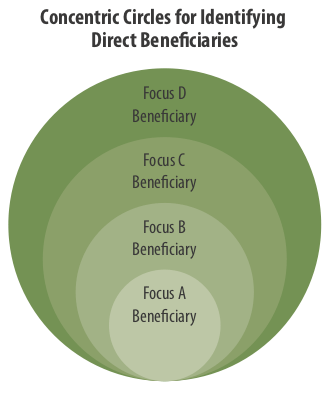

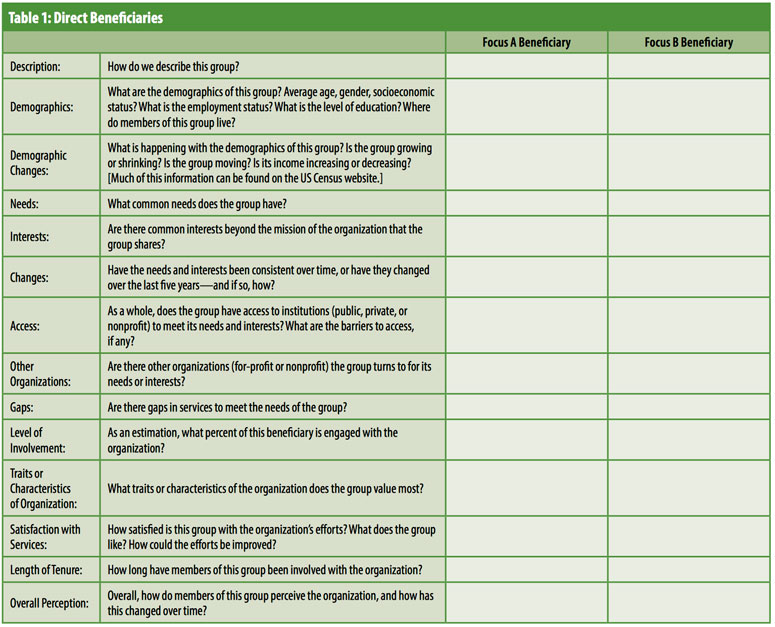

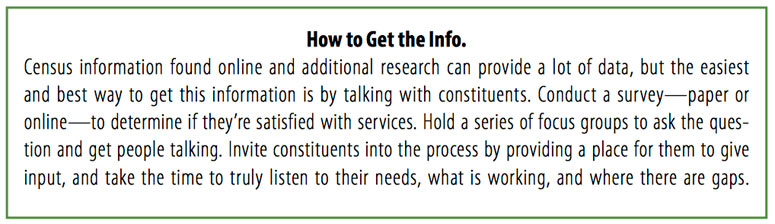

A market analysis of direct beneficiary subgroups helps leadership better understand how relevant the organization is to each group. Once the focused subgroups have been identified, a table can be set up to lay out and answer the relevant questions, as shown in Table 1.

Market forces may affect beneficiaries differently. For example, beneficiaries who receive services funded by a third party may be impacted differently than those who pay directly. For this reason, it is important to understand the different segments and how changes within them may affect the organization’s ability to accomplish its mission.

Additionally, for organizations where board, staff, and constituents come from different parts of the community, it is important to make sure that there is a shared understanding of the needs and perceptions of direct beneficiaries. This empowers constituents to be a true part of the organization, having a say in the future direction and building of an organization that maximizes impact by meeting their needs accurately. It also sets up leadership to understand how the remaining segments of the market will influence the organization’s ability to deliver impact and build sustainability.

Other Beneficiaries/Funders

Beyond direct beneficiaries, there are many other groups that benefit from the efforts of nonprofit organizations. These may include public agencies, such as school districts or police or housing authorities. Another example might be businesses that benefit when an organization provides opportunities for employee–community engagement; or homeowners in a particular neighborhood that might benefit from the nonprofit’s presence. Other beneficiaries include foundations and funders who further their missions and interests by supporting nonprofit organizations. We consider all these groups to be “other beneficiaries” and, similar to direct beneficiaries, seek to understand their demographics, needs, and motivations for supporting the organization.

This is an opportunity for leaders to think broadly about the benefits the organization’s work brings to segments of the community it may not normally consider. Understanding this segment of the market helps organizations not only in honing their impact but also in strengthening their revenue strategy and remaining relevant to funders.

Dennis Young’s normative theory of finance offers four different types of benefits organizations may provide to various segments of their community:

- Group Benefits. Subgroups of communities with shared values may be interested in supporting an organization’s mission that aligns with their values. For example, people who like animals may be supportive of a dog rescue organization, and those who were in New York on 9/11 may support an organization that assists 9/11 victims. Identifying common values that align with an organization’s mission can help identify groups that might support the organization.

- Public Benefits. When a large segment of the community is supported or strengthened as a result of an organization’s efforts, the organization is said to have “public benefits.” Types of organizations that may benefit the public in this way include, for example, health and wellness programs, juvenile mental health programs, and employment-based programs. When an organization can demonstrate specific public benefits resulting from its work, this presents an opportunity to pursue public funding.

- Private Benefits. Individual consumers may also benefit from an organization’s efforts. By identifying through market analysis individuals who benefit from an organization’s efforts, the organization may discover some willing and able to pay for the services and benefits they receive, presenting another revenue opportunity.

- Trade Benefits. Institutions and businesses can benefit from associating with a nonprofit and its mission. For example, cause-related marketing—when a business publicly displays its support of a nonprofit—benefits the business by associating it with the positive brand of the nonprofit organization.4

Once an organization’s leadership understand which segments of the community are benefiting from their efforts, there may be an opportunity to explore different sources of revenue—for instance, by asking those who benefit to contribute to the organization through program fees or philanthropic support.

To identify other beneficiaries, leadership should think expansively about the following questions:

- Who benefits from the results of our work?

- Who else’s missions are more successful because of our work?

- Do corporations or small businesses gain by being associated with us, and if so, how?

- In what ways are homeowners or property owners better off because we are in their neighborhood?

- Are there other initiatives that are less costly because of our work?

For an example of other beneficiaries, consider an organization that provides environmental education for schoolchildren in a public park. The direct beneficiaries are the schoolkids. However, by hosting programs in neglected parks, local crime drops and property values rise. Additionally, by providing experiential learning opportunities, educational outcomes improve—a favorite cause of the local business community. Lastly, by engaging volunteers from corporations in park cleanup and other events, the organization provides a way of involving its employees in the community, one of many factors contributing to employee satisfaction.

In this story, we’ve identified several beneficiaries, including:

- Local property owners

- School districts

- People interested in educational outcomes

- The police department

- Local businesses

- Larger corporations

- People interested in environmental science for youth

- The general public

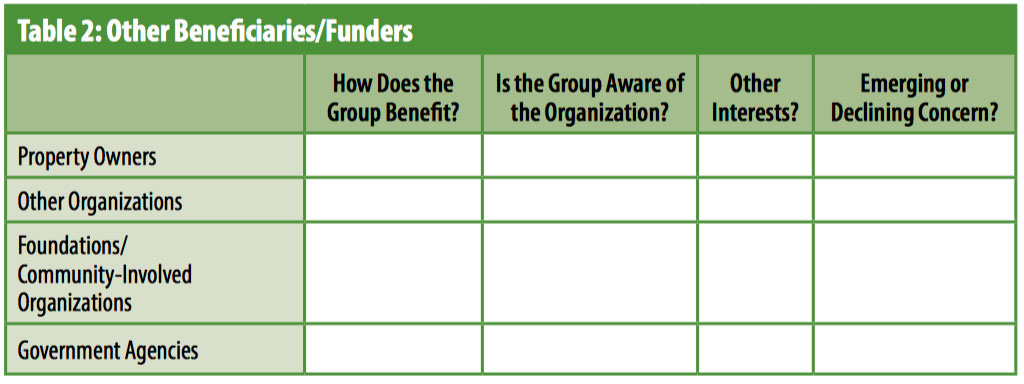

Each of these beneficiaries can be examined in more detail, not only to maximize impact but also to discover possible revenue sources. The analysis should answer:

- What is the motivation or goal of the beneficiary in supporting your organization?

- How aware are the beneficiaries of the organization’s efforts?

- How much do they care about the organization’s efforts?

- Is their awareness of the organization and concern about the issues growing or declining?

- What else is this particular group interested in?

A table like the one below may be helpful for capturing answers to these questions.

There’s a direct link between other beneficiaries and an organization’s revenue strategy. Understanding this market component, the motivations of other beneficiaries, and how they’re changing will help leadership stay close to those funding the organization’s impact, explore potential new sources, and build organizational sustainability.

Other Organizations

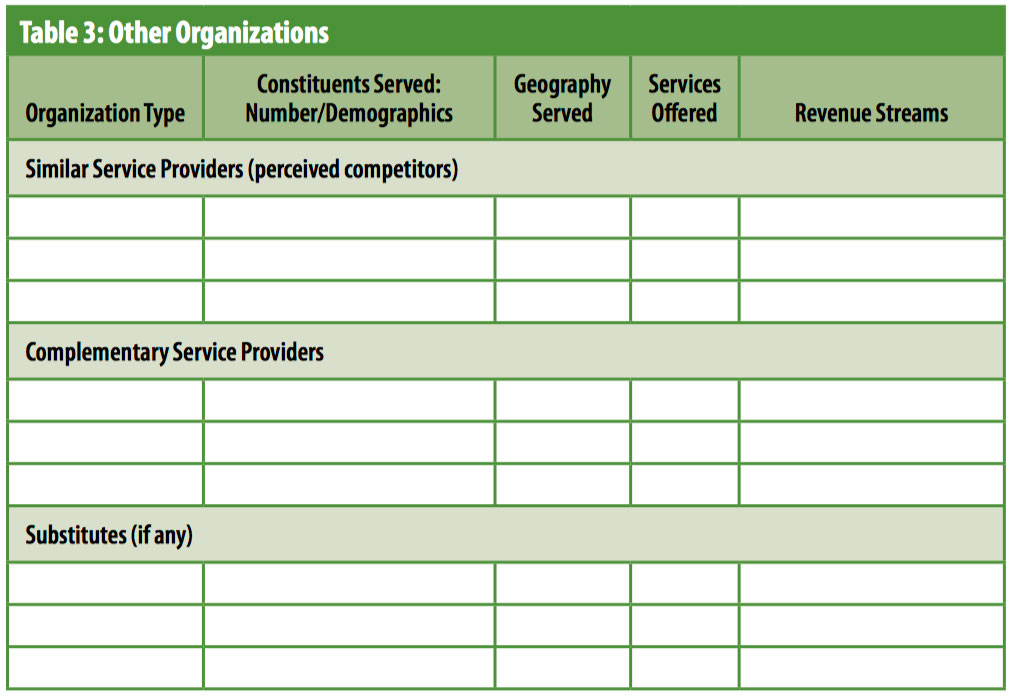

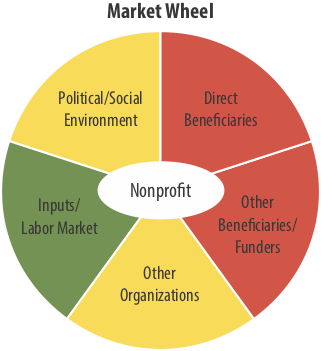

The competition and cooperation that nonprofits encounter from surrounding organizations is one of the more dynamic and confusing components of market analysis. On the one hand, there is intense pressure from funders and other beneficiaries for nonprofits to cooperate or collaborate with other organizations and form strategic alliances. On the other hand, fierce competition for funding presents a challenge—whether for philanthropic or earned revenue. These realities of the nonprofit landscape make it difficult to determine which organizations are competitors and which are complementary and thus ripe for cooperation or potential collaboration.

Nonprofit executives shouldn’t spend too much time worrying about this, as it is often a false distinction: an organization may both pose competition as well as present an opportunity for collaboration. Similarly, in the private sector, companies frequently both compete and cooperate. For example, restaurants compete with one another for diners, but they also gain business by locating near one another and collaboratively providing parking and other amenities. Likewise, Internet providers compete for subscribers but might work together to fight the NSA.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Blurry boundaries between the nonprofit and private sectors are another consideration when thinking through other organizations in the market. It is important to consider both other nonprofit organizations and for-profit businesses when analyzing the competitive landscape. In some cases, it may also be wise to include government agencies or quasi-governmental service providers.

Leadership also need to consider substitutes for an organization’s services. For example, while other restaurants may be direct competition for a dining establishment, a bicycle delivery service is a substitute. For an art museum, a direct competitor might be the science and technology museum across the street or an art gallery located across town. However, thinking even more expansively, a movie theater or bowling alley might also be a substitute. To fully understand how other organizations affect a nonprofit’s business model, leadership need to think broadly about how they define competition.

A laundry list of other organizations can be daunting to analyze. Listing the organizations and then prioritizing based on a task force’s perceptions makes the analysis more manageable. Once prioritized, briefly understanding demographics and geography served, services provided, and revenue streams will be helpful. Table 3 captures the foundational understanding.

While this table will provide leadership with a list and some attributes to compare characteristics of organizations, there are other methods that can be used. Peter Frumkin and Suzi Sosa, in their Nonprofit Quarterly article “Competitive Positioning,” offer one such model that creates a matrix of characteristics of similar organizations, allowing leadership to compare and contrast.5

Putting the organization in context, and understanding how it interacts—or could interact—with other nonprofit organizations in the community, provides an opportunity for greater collaboration as well as a way to surface the distinct advantages an organization brings to its beneficiaries and mission.

Inputs/Labor Market

There is no question that, with his brilliant idea for the Apple computer, Steve Jobs intuitively understood what people really craved. But, without the engineering expertise of Steve Wozniak, the Apple might have remained simply a dream. Understanding customers is not enough; leadership also need to be mindful of the resources and skills necessary to meet customers’ needs. For nonprofit organizations, this means not only understanding how those who benefit from their services or programs are changing but also being mindful of the inputs necessary to generate impact. The biggest input for nonprofits is people. To have a sense of the market, leadership need to understand an organization’s competitive position in attracting and retaining quality talent. This is especially true if an organization’s mission requires specialized skills.

In his excellent monograph Good to Great and the Social Sectors, Jim Collins talks about having the “right people on the bus” as a critical first step to achieving greatness.6 Unfortunately, in the spirit of trying to serve as many constituents as possible, most nonprofits shortchange their staff with low compensation or poor benefit packages. This mentality is one of the reasons why the nonprofit sector has a higher turnover rate than the for-profit sector, leading to shortsighted budget decisions in which the cost of recruiting and training employees is often uncalculated.

The accessibility and objectivity of salary surveys turn the focus of many discussions on staffing and satisfaction to compensation. However, today’s employees want more than just monetary compensation: they want a meaningful work environment that engages and develops them over time, valuing their opinions and professional perspectives. Therefore, when assessing the state of the labor market, leadership need to look beyond compensation to the overall work environment and ability to attract, develop, and retain key talent.

Just as leadership conduct surveys, interviews, and focus groups with constituents and stakeholders, an employee satisfaction survey is a useful tool to assess this part of the market. Questions focused on whether employees feel they have the tools necessary to perform their jobs, are provided opportunities for development, and feel they are valued can be helpful in determining how significantly job satisfaction may influence the organization.

Additionally, a vibrant discussion around some key questions will help to surface concerns in this area:

- What is our turnover rate, and why are people leaving?

- How long does it take to fill open positions, and are there particular positions that are harder to fill?

- What is the ratio of our lowest to highest salary?

- How much do we invest in or provide professional development?

- Do we partner with and empower our staff to lead, valuing their experience and input in guiding the organization?

Too often, nonprofit staff are taken for granted, but compensation is typically the largest expense for an organization, and employee skills are among the biggest drivers of impact. Beyond the cliché of saying “people are our most important asset,” leadership need to understand the market for attracting, developing, and retaining talented employees and the effect that may have on the organization’s ability to continuously deliver deep impact and generate financial resources.

Political/Social Environment

The last element of the nonprofit market that can affect an organization’s ability to accomplish its mission while remaining financially viable is the political and social environment in which the organization operates. Public policy affects every nonprofit organization. For example, organizations that rely on government contracts are affected by the debate over the role of public funding in our country. The debate may happen in Congress but the ramifications are local, and the social and political environment in each organization’s community helps to inform the discussion. Similarly, on the impact side, public policy is an important tool for environmental organizations to achieve their mission-related goals, such as protecting wetlands or improving air and water quality. Regardless of the organization, the level of political and social support for an organization’s values and mission affects its business model.

Nonprofit leadership and staff often deeply understand this aspect of the market; however, they may not take the time to articulate their knowledge or educate the board. Holding space for discussion of key questions and reviewing research interviews or survey data can bring this aspect of the market to light and provide context for strategic decision making. Key questions for discussion and research include:

- Is there public awareness of and support for the importance of the organization’s mission?

- Has that awareness increased or decreased over the last five years?

- Is the issue controversial in the public’s mind? How and why?

- Is there support for the organization’s strategies or theory of change to achieve impact? (While many people may want the same outcome, the “devil is in the details,” and people may not support the organization’s strategies. Having clarity on specifically what about the organization the public supports is important.)

- Who are key voices with respect to the organization’s issue in the local, state, and federal government, and does the organization have a contact in or direct connection to these people?

- Is there an association or network that provides lobbying or information on the organization’s issue, and is the organization connected with it?

It is important to note that I am not proposing that there needs to be universal support for an organization’s mission or theory of change. However, knowing the importance and level of public support and how it is evolving will provide guidance to leadership in setting organizational strategy. For example, if the organization relies significantly on public funding, it is imperative that it engage in an appropriate level of advocacy and perhaps lobbying of elected officials, either on its own or through an association. BoardSource has an excellent resource, “Stand for Your Mission,” which advises boards on how to engage in advocacy.7 This market analysis discussion will help the board understand the importance of this role.

Tying It All Together

Organizational sustainability is an orientation, not a destination, because organizations must continually evolve to be sustainable. When making strategic decisions to strengthen sustainability, leadership must understand how the market affects their business model. Tactics for sustainability must constantly evolve as constituent needs, programmatic best practices, revenue and talent availability, the landscape of competitors and collaborators, and community perceptions change. Market analysis enhances sustainability by giving leadership a clearer understanding of how all components of the market are changing and how their evolution might influence the organization’s business model.

The amount of influence each aspect of the market has on a nonprofit’s business model varies. For example, changing constituent needs or labor markets may drastically affect an organization’s ability to achieve its intended impact, whereas a change to other beneficiaries or increased competition may affect an organization’s financial viability somewhat less drastically.

Analyzing the market won’t, on its own, dictate a foolproof strategy for an organization to cope with its changing market. However, understanding how the changing market is influencing the organization will give leadership an idea of how their mission-specific and fund-development activities could be altered to be more responsive to market trends. Some programs may be well positioned to seize partnership opportunities or meet the changing needs of constituents, while others may need to be redesigned or even phased out.

Exploring each aspect of the market individually can be insightful, but putting the segments of the market together to obtain a comprehensive look at the forces influencing an organization yields the most useful information.

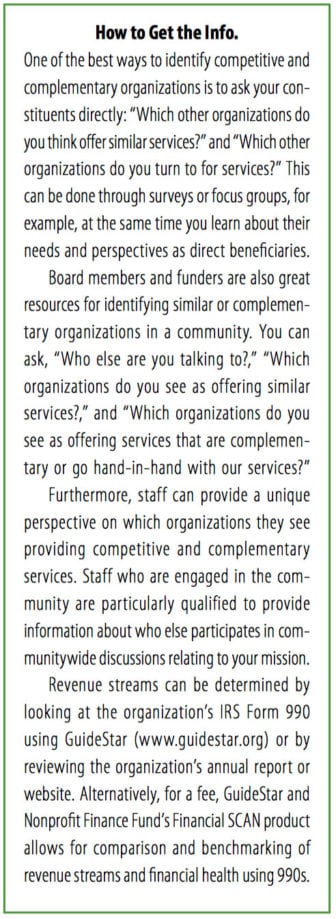

After analyzing each market segment individually, leadership can ask the following questions to prioritize which market aspects are currently impacting their organization’s business model most (and see Table 4):

- How quickly is each market component changing relative to the others?

- In relative terms, how significantly would a change impact the organization’s sustainability (impact and financial viability)?

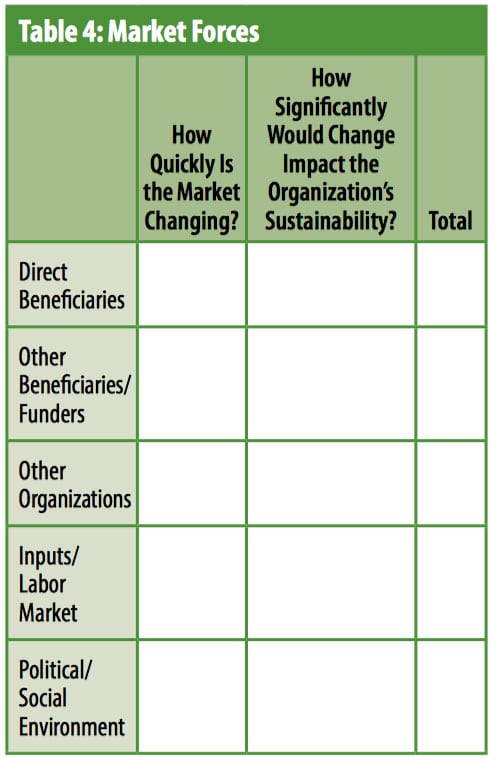

One way to prioritize the relevance of different market forces for an organization is to rate the speed at which each is changing and the significance with which each impacts the organization on a scale of 1 to 5. Leadership can then compare the results to determine which market aspects need immediate, strategic attention.

To help depict how strongly each market aspect is influencing an organization’s business model, the market wheel graphic can be color-coded in the following way:

- Red: Score 8 to 10, “High Priority.” These aspects of the organization’s market are either changing rapidly or having a significant effect on the organization’s business model. They must be addressed when setting strategy.

- Yellow: Score 5 to 7, “Bears Watching.” These aspects are on the edge, perhaps not as high a priority as other aspects of the market but they should be watched to understand better how they may influence the organization’s business model.

- Green: Score 2 to 4, “Stable Influence.” These aspects are relatively stable and not in need of in-depth monitoring.

An example follows:

For this example, the market wheel would be color-coded to reflect the urgency of strategically addressing different market influences:

Conclusion

Nonprofit organizations are vehicles for community engagement—groups of individuals coming together to make their community a better place. However, when it comes to setting strategy, leaders often don’t consider all the aspects of the community that influence their ability to achieve the mission but instead focus solely on the desires of those who are funding their mission.

To ensure relevance of the organization to its community, however, the board’s first priority needs to be those whom the organization directly serves. With an understanding of the changing needs of this group, the board is better positioned to then explore how all the elements of the market influence its ability to impact the group.

As communities change, so do the markets in which nonprofits operate. Shifting demographics, political and social pressures, and competition and resources require leadership to be continually ready to adapt. To do so, leaders must understand not only how their own programs deliver impact and financial viability but also how the market is influencing their ability to do so.

This framework provides a holistic method for executives and boards to explore their market and prioritize which aspects need strategic attention. Additionally, it sets up a conversation about how ready an organization is to change, and whether it truly has the capacity to respond to market influences. Having an engaged and committed board and staff that reflect and represent the organization’s core constituents can dramatically expedite this process. While it may seem intense, by undertaking a market analysis an organization will become both more aware of its position in the community and more empowered to help build a stronger one.

Notes

- John Carver, Boards that Make a Difference: A New Design for Leadership in Nonprofit and Public Organizations, 3rd ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006).

- See Steve Zimmerman and Jeanne Bell, “The Matrix Map: A Powerful Tool for Mission-Focused Nonprofits,” Nonprofit Quarterly, April 1, 2014.

- Financing Nonprofits: Putting Theory into Practice, ed. Dennis R. Young (Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2006).

- Ibid.

- Peter Frumkin and Suzi Sosa, “Competitive Positioning: Why Knowing Your Competition Is Essential to Social Impact Success,” Nonprofit Quarterly, March 20, 2018.

- Jim Collins, Good to Great and the Social Sectors (New York: HarperCollins, 2005).

- BoardSource, “Stand for Your Mission.”

- Zimmerman and Bell, “The Matrix Map.”