Editors’ note: This article, first published in print during June-1997, has been republished for Nonprofit Quarterly with minor updates.

Most grassroots groups tend to focus their fundraising on two inefficient and risky strategies: grant proposals and benefit events.

Grants are problematic for at least two reasons. Foundations and corporations, which distribute grants, provide only 12% of the private-sector money available to U.S. charities, so groups that rely on grant funding are chasing a small piece of a very large pie. Furthermore, fewer than 15% of all proposals submitted are actually funded, which makes for lousy odds.

Benefit events, on the other hand, are great for identifying new donors and increasing the visibility of your group, but as a pure fundraising strategy they’re terribly inefficient. Consider the “work-to-profit” ratio: If you applied the same number of staff and volunteer hours and the same expense budget to other strategies, could you raise more money hour-for-hour and dollar-for-dollar? In most cases, the answer is a resounding yes.

So where should you put most of your fundraising effort? Find and cultivate individual donors, especially potential major donors. In a typical annual campaign —seeking unrestricted individual gifts that all groups need to survive and prosper — just 10% of the donors provide a whopping 60% of the money. If you identify the right people and approach them in the right ways, you can build an effective major donor program to cover a big piece of your budget.

PUTTING THEORY INTO PRACTICE

To understand how this works, consider The Wildlands Project of Tucson, Arizona, a nonprofit conservation group working to establish a network of linked wilderness reserves across North America.

When I began working with Wildlands in January 1996, the organization had an annual budget of $300,000, most of which came from three foundations. Board and staff were understandably nervous about relying on such a narrow funding base, and sought help both to diversify foundation support and to build a major donor program that would increase their small donor pool.

In designing a fundraising strategy to reach individual donors, we were restricted by two factors:

The Wildlands Project is not a membership group and, for two reasons, did not want to become one. First, it is not equipped to manage and service a large membership base of $25 donors. And, perhaps more important, because one of the organization’s primary goals is to improve cooperation among national conservation groups, the board chose to avoid mass mailings and the perception of competing with other groups for their members.

The project could not solicit many major gifts in personal meetings. The Wildlands Project works throughout North America and has an international board that meets just twice each year. Given the vast geographic distance between staff, board, and prospective donors, and the relatively low buy-in they had decided on for the major donor program ($100 and up), it would have been too costly and logistically difficult to solicit many prospects in person.

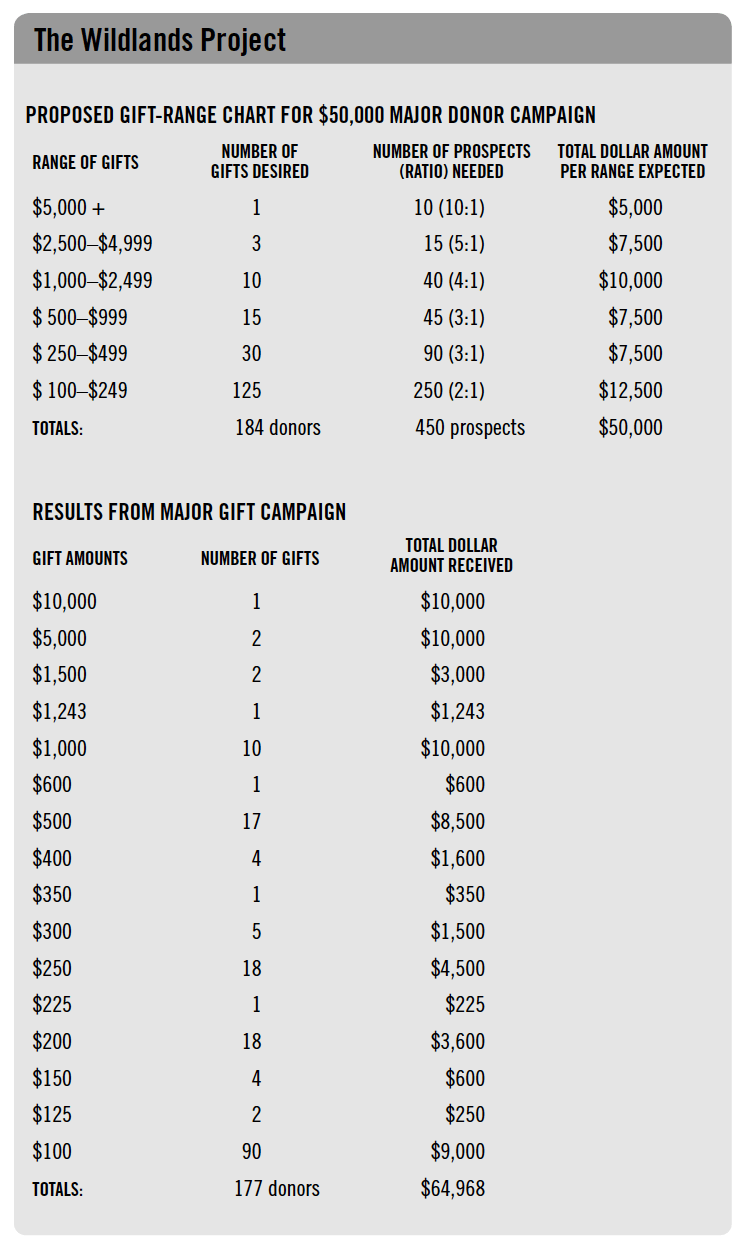

As a result of these considerations, we decided to build the campaign around small, personalized mailings. Our goal: 200 individuals donating between $100 and$5,000 each, for a total of at least $50,000 in 1996.

WORKING THE “HOUSE LIST”

For starters, we reviewed the group’s donor list and found 265 people who had given $50 or more during the previous two years. This was the first, and best, pool of prospects for major gifts.

To solicit them, we mail-merged their names into an appeal letter using the office laser printer. The mail merge allowed us to personalize each letter with name, address, and salutation: “Dear Fran” instead of “Dear Friend.” The letter also requested substantial gifts: “Whether you can contribute $100, $1,000, or more, we need your help.”

The letter was a page and a half long — front and back on board letterhead — and included signature spaces for both the chairman and the board president. (One is a prominent biologist, the other a nationally known conservation activist.) Both men signed all letters by hand in colored ink.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

So far, so good — personal letters signed by real human beings. We took this stack to the next board meeting and read off the names with the request, “If you know any of these people, raise your hand and add a note.” The blank half-page on the back would accommodate their personal greetings.

At least 100 of these letters ended up with personal notes. A few contained five or six notes, which makes for a compelling request (talk about peer pressure!). Board and staff enjoyed this exercise and were eager to learn which of their contacts contributed.

As a final touch, we hand-addressed the envelopes and applied a first-class stamp. Hand-addressing is the most effective way to ensure that the envelope is opened; a “live” stamp also helps. We included a response envelope and a remittance card, with check-offs beginning at $100 and going up to $2,500, to indicate that we were serious about receiving a substantial gift.

This appeal generated an impressive 33% return and nearly $30,000, including one gift of $10,000 and another of $5,000. After subtracting these two big contributions, the average donation (including 34 gifts of less than $100) was $164. This one mailing produced more money from individuals than everything Wildlands had tried during the previous two years. This group of donors was solicited again in December, seven months after the first letter, and the checks continued to come through March, generating more than $20,000 in additional gifts.

BRING US YOUR NAMES

Once the first mailing was completed, we asked board members to go through their personal address books, Rolodexes, and databases to identify prospective donors. Their instructions: Put aside any concerns about whether these prospects can afford to give $100, and focus on their relationship to you and their concern about the environment.

We also contacted several national conservation groups (The Nature Conservancy, National Audubon Society, The Wilderness Society, etc.) to request copies of their annual reports. These booklets contain pages and pages of major donors, sorted by the size of their gifts. After photocopying these donor lists — 62 pages of names— we distributed packets to all board and staff and asked them to check off anyone they knew.

We reasoned that these people would make excellent prospects because they had a relationship to the solicitor, they had proven their concern about conservation issues, and they had proven their ability to make a big gift. The process of reviewing these lists “triggered” other names, which increased our pool of prospects.

Needless to say, list screening is miserable work: boring, time-consuming, and seemingly pointless. One board member was embarrassed to review more than 5,000 names and find only five people he knew — but one of those five came through with $1,000. Now he doesn’t need to be convinced.

In the many cases where board and staff knew prospects but did not have an address or phone number, we used a CD-ROM product available at the public library. PhoneDisc, an electronic compilation of most phone books in the country, provided good addresses for at least two-thirds of our “missing persons.” As an alternative, try one of the many online databases. Our local library’s Web site — www.lib.ci.tucson.az.us — links to several directories, including AnyWho, Switchboard, The Ultimates, WhoWhere?, and Yahoo. Click on “Web links,” then “directories.”

After gathering names and addresses, we again mail-merged them into an appeal letter signed by the person who knew them best. After the signer added a personal note, other board and staff were asked to add notes where appropriate. As before, we hand-addressed the envelopes, affixed a first-class stamp (from the Endangered Species commemorative series!), and included a response card and remittance envelope. For these new prospects, we also enclosed a brochure about The Wildlands Project.

Through this process, board and staff identified and solicited more than 400 additional prospects; most received two letters six months apart. The result: Forty donors provided $11,650 in large gifts, with two dozen sending smaller donations.

All told, we contacted 700 major donor prospects; 177 responded with nearly $65,000 in contributions of $100 or more. About one-third of these gifts were received from board members and at benefit events, and a few others were unsolicited, but the rest were raised through the mail.

WHAT WE LEARNED

- Personal attention makes a big difference. The old cliché is true: People give money to people, not organizations. The more personal the contact, the more effective our fundraising. Next year, we plan to approach selected donors and prospects by phone and, when feasible, in person.

- You don’t need rich people. Most of our contributors are college faculty, non-profit staff, doctors, activists, teachers, homemakers, retired people, etc. We have very few “name” donors.

- Small is beautiful. Big national groups will not give this much attention to $100 or $500 donors, but grassroots groups can and should. This is the strategic advantage of being small.

- Don’t try for more major donors than you can service. Our goal was to enlist 200 major donors in 1996. Given our limited staffing, we figured this was the largest number we could maintain strong relationships with. We continue to send them personal notes and treat them as part of the family.

- You can’t save time. Every stage of this process—screening lists, mail-merging and hand-signing the letter, writing notes, hand-addressing envelopes, etc. — is time consuming. If you want to build a successful major donor program, you can’t take shortcuts.

- It works. This successful major donor strategy tripled income from major donors of The Wildlands Project within one year. Try these techniques with your own organization and watch what happens.