As Cyndi Suarez asserts in her article on COVID-19 and social change, big disruptions lay the groundwork for big social change that shifts away from “small fixes to the current systems and norms” to “breaks with the past—change that breaks the frame, marking the end of one period and the beginning of another.”

But how could that kind of change be mobilized now—especially when, as she asserts, advocates are so used to a slower pace of change and all that accompanies it?

Yesterday, Business Insider reported that Spain, in an effort to right itself in the wake of the coronavirus, has instituted universal basic income (UBI) with an eye toward retaining it as a permanent policy. And Spain is not the only country to consider the measure; writing for Wired UK, Gian Volpicelli notes:

In the US, Democratic lawmakers asked the government “to provide for an emergency non-taxable Universal Basic Payment of $1,000 per month to all adult Americans” during the crisis. In the UK, a cross-party coalition also pushed for the creation of a UBI scheme. In Italy, the founder of the Five Star Movement, Beppe Grillo, wrote a blog post calling for the establishment of a UBI system in order to help the “millions of Italians [who] won’t have a secure income in the next few months.”

In other words, UBI is an idea whose time might have come as a companion to a scourge that has rapidly dismantled large parts of our economy. It’s just one of a number of policy openings that social movements will find when they look at the range of actions taken to mitigate the impact of the virus. We have also seen the early release of prisoners who pose no danger to the public and money freed up to house homeless families permanently to keep both groups out of settings where contagion could prosper.

These measures are not only appropriate to the urgency of the moment; they are actions that ought to have been policy prior to the pandemic and which many of us would like to see extended permanently. Many of these initiatives, once they have passed on a temporary basis, may have traction for more permanent adoption and a growing understanding as important opportunities for the future health and well-being of our nation.

In other words, this is not a time when movements should place their issues on the back burner because all anyone is talking about is COVID-19. Nor is it a time when nonprofits should attend only to shorter-term goals and immediate relief. It is time to note what opportunities are opening up for policy change that provides long-term benefits for our communities and make the most of this painful moment.

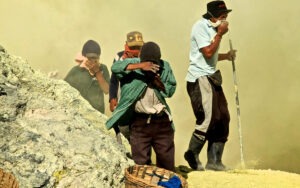

Essential Supports for Essential Workers

One of the most glaring lessons to the public from the pandemic has been the definitional quest for the “essential worker.” These include grocery store workers, farm workers, and home care workers, all of whom tend to be underpaid and, in the last two categories, tend to be of color. A lack of benefits, sick days, and other supports have emerged front-and-center as matters that need to be addressed during this crisis.

For instance, in Illinois, the state has agreed to cover “most, if not all,” costs of child care for essential workers in health care, human services, government services, and infrastructure. While the money is surely insufficient for the risk assumed, a number of corporations, including Amazon (which owns Whole Foods), Albertsons, Kroger, and Safeway all announced a minimal $2-an-hour pay raise as partial compensation for the fact that frontline grocery workers are in harm’s way.

Of course, before the pandemic, it was not exactly a secret that having affordable childcare is an essential component to maintain stable employment. Now that we know who is essential, we must be sure to carry these values forward in our policies, paying the workers upon whom we depend fair wages and ensuring they have the childcare support they need.

Did you know that 179 countries in the world have paid sick leave? It’s incredible that the United States is not among them. As Dr. Jody Heymann, founding director of the WORLD Policy Analysis Center (WORLD) and former dean of the University of California, Los Angeles’ Fielding School of Public Health, points out, before COVID, “seven in 10 of our lowest income workers don’t have a single day of paid sick leave…of food service workers, four out of five lack sick leave; three out of four childcare workers lack sick leave. This is a devastating impact on them and their families, but also to everyone they come into contact with.”

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act—also known as “Phase II” of the COVID-19 legislation, with Phase I being the initial medical relief bill and Phase III being the $2.2 trillion CARES bill—grants, according to the Washington Post, “two weeks of paid sick leave at 100 percent of the person’s normal salary, up to a $511 per day cap” as well 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave at 67 percent of the person’s normal pay, up to a $200 per day cap. The bill still does not provide paid sick leave for all—businesses with over 500 employees are excluded from its provisions and businesses under 50 employees can request waivers.

Still, the principle, if not yet the reality, of a right to sick leave has definitely gained considerable support. But there is more. How, many people asked, can the government contain a pandemic when so many cannot afford care?

US Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar has an easy answer for that one: the government will pay. As Jacqueline LaPointe writes for Recycle Intelligence, “During a Coronavirus Task Force briefing on Friday, Azar stated that HHS will use some of the funds from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act to pay hospitals Medicare rates for the care of uninsured COVID-19 patients. The department will use the same mechanism used for paying providers for COVID-19 testing for the reimbursement of uninsured COVID-19 treatment. However, as a condition of reimbursement, hospitals cannot balance bill uninsured patients for COVID-19-related care.”

So, in other words, Medicare will pay for all patients lacking alternative forms of payment—that’s sounding pretty close to Medicare for All, doesn’t it?

After the collective experience of a pandemic in which paid sick leave and guaranteed care has become the norm, again, it will become vital to carry these values forward in our policies.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

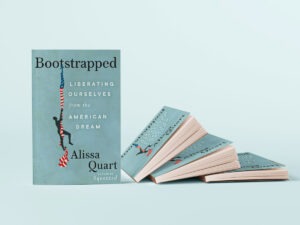

Income Supports: Unemployment Insurance and Universal Basic Income

It has gone largely unremarked, but the idea of a universal basic income did not originate with the presidential campaign of Andrew Yang. Indeed, the largely Republican state of Alaska has provided a basic income for its residents since the 1980s, with payments varying from $1,000 to $2,000 per citizen per year. In 2019, each Alaskan resident received a check of $1,606 based on royalties earned off of the state’s oil wealth. A family of four in 2019 received four times that or $6,424. While no one lives off their dividend checks in Alaska, the policy does help reduce the state’s overall poverty rate.

The CARES bill, of course, provides $1,200 per adult and $500 per child for families with incomes below $75,000 (or $150,000 for couples) on a one-time basis. As such, it stops far short of the goal of a universal basic income policy, which is to set an income floor to guarantee that everyone enjoys at least a common minimum standard of living. Still, the parallels between the CARES bill and a universal basic income were widely noted in the media—the idea has definitely moved from fringe to mainstream.

Another development, perhaps even more significant, is the expansion of unemployment insurance. Long neglected by US policy, the CARES Act not only adds $600 a week to most unemployed workers’ weekly payments for a four-month period, but it also greatly expands who is eligible for unemployment insurance to include gig economy workers and contractors. It might be noted that it was not so long ago—as in the first quarter of 2020—when there was fierce resistance, including within the nonprofit sector, to the idea that gig economy workers and contractors might need to have benefit support like regular payroll employees. Now that we have seen the necessity of a strong unemployment insurance, some minds, we would hope, have changed. Still, as with every other social policy advance, these policies will not remain as policy unless we strongly advocate for them.

Student Loan Debt

Student loan debt is another policy area in which federal action could provide immediate, major relief for millions of Americans. It’s the financial equivalent of the surveillance system from George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four: wherever you go, whatever you do, if you have student loan debt, that burden follows you everywhere and influences every financial decision you make. As we plan for the new, more connected world that will emerge from this crisis, we cannot leave 45 million fellow citizens strangled by debt.

NPQ has followed the rapid evolution of student debt policy as formulated by the Trump administration and the 116th Congress, thanks to our contributor Marian Conway. In early March, the national student loan debt burden was increasing by $250,000 every minute. Then legislators began proposing relief. A week later, interest rates were lowered to zero and borrowers could request payment suspension. By Tuesday, the Department of Education realized that more people needed suspension than not, and flipped the default—all federal student loan payments are suspended until September 30th unless borrowers call to request otherwise.

Let’s be clear: Student debt is not canceled. Payments have not been assumed by the Department of Education, which was what Representative Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) originally proposed. Borrowers and lenders are, like the rest of us, frozen in time, awaiting the moment Americans hit the “restart” button on the economy to resume business as usual.

But business as usual wasn’t working that well. The US student debt burden was $1.6 trillion—about the same as the national GDP of seven small countries combined. A borrower defaulted, on average, every 26 seconds—default that leads to lowered credit scores, garnished wages, even withholding of tax returns or Social Security benefits. (Three million borrowers of student debt are 60 years old or older.) The debt burden is preventing people from participating in the economy, and like most burdens, it fell disproportionately on poor communities and people of color, especially Black communities.

The debt burden cripples individuals’ financial futures, but that frame ignores the larger reality the coronavirus crisis has made clear: Individual futures are our collective future. We cannot imagine an economy that emerges stronger, more resilient, and more inclusive, while ignoring the individual burdens people face. We can’t imagine an economy that emerges at all from this crisis if we keep 45 million people financially defined by their debt. And for many people, student loan debt is the biggest burden they have to bear.

Something must be done.

Pressley and Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Representative Ilhan Omar (D-MN) have been among the most vocal proponents of eliminating student debt during this crisis. Pressley and Omar have jointly proposed the Student Debt Emergency Relief Act, which would cancel at least $30,000 of debt for every borrower and have the Department of Education assume payments for the time being.

Pressley wrote, “During this public health emergency, no person should have to choose between paying their student loan payment, putting food on the table or keeping themselves and their families safe and healthy.” We at NPQ ask: Do we need the “during this public health emergency” part?

Imagine what the economy would look like with an additional $1.4 trillion available for use by people who could patronize community businesses, subscribe to local papers, donate to food banks, and consider purchasing a home. (Some student debt is held by private lenders, and the Department of Education doesn’t have as much authority over that.) A study by the National Bureau of Economy Research found that even partial debt cancellation led borrowers’ income to increase by $3,000 over a three-year period, lowered their debt in other areas by as much as 24 percent, and increased their job and geographic mobility. Isn’t that exactly what we need to get the economy moving again?

Canceling student loan debt isn’t just good for the economy. It addresses racial disparities in wealth and education, and contributes to the well-being of citizens whose mental health is imperiled by large debt burdens. It sends a message that when this new, post-crisis economy emerges, it will be an economy for all of us who’ve finally recognized that we’re in this together.

Imagining a More Inclusive America

These are just a few of the policy opportunities that we may find when we examine responses to an immediate threat. We do not pretend that this is as exhaustive list. We also don’t pretend that movement in a positive direction is either inevitable or automatic. As we noted in NPQ before, after World War One and the 1918 flu epidemic, US policy took a turn in anything but a more inclusive democratic direction. In the 1920s, the borders were closed and the Ku Klux Klan enjoyed a resurgence. On the other hand, in the aftermath of World War II, a social welfare state backed by strong labor unions emerged, resulting in a major decrease in wealth and income inequality that persisted until the 1970s, and civil rights organizing got a major boost. The Double V campaign, in which Blacks aimed to fight fascism abroad and Jim Crow at home, seeded many civil rights gains that followed.

The future, in short, is in our hands. Let’s seize the reins and build a more inclusive, equitable, and democratic culture and society.