“Two of my primary care patients have died of COVID. Both were in intensive care units. And, both basically died alone, without support of their families—which seems to me probably the worst way to die,” Dr. Colleen Surlyn, MD & MPH and the Medical Director of Care Coordination of the San Francisco Health Network, said to NPQ.

The United States has reached close to 230,000 deaths from COVID-19, and this is most likely an undercount; the true number could be as high as 500,000. That includes the rate of “excess deaths,” which is up 26.5 percent from previous years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Many who are dying are doing so alone, away from their loved ones.

A May 2020 Census Bureau poll found one-third of Americans are exhibiting signs of clinical anxiety or depression, and healthcare workers are taking the brunt of this exposure, bearing witness to immense uncertainty, trauma, tragedy, and loss of human life. Having patients die may be a reality of care work, but the scale in 2020 is extraordinary. To put this impending wave of intergenerational trauma in perspective, it would take over 23 years, working 24/7 without any breaks, to provide a single hour of counseling for every person affected by the lives officially counted as lost.

“Just thinking about the pain and suffering of that person and of their families is really a lot to bear,” says Surlyn, who, reflecting on the mental health toll on health care professionals, added, “But I think for people that are in the hospital lot, seeing that degree of human suffering is incredibly hard and a huge psychological burden.”

Not being able to say goodbye, share final moments together, and express love has detrimental effects on grieving family members, but healthcare personnel in proximity to those who have passed are not unaffected. Nurses or nursing assistants are often the last line for FaceTimes, phone calls, and emotional support as patients pass away, all while wearing layers of protective equipment to protect them from the virus, but not the emotional toll.

The pandemic has placed healthcare personnel across roles at particular mental, physical, social-emotional, and psychological risks. If these realities are not acted on by national, local, and health system leadership, this community of caretakers is on track to experience a widespread mental health crisis for years to come, in tandem with fighting the pandemic.

Primed for Burnout

Many aspects of the American healthcare landscape primed healthcare workers across roles to be particularly at risk for exposure to various forms of trauma and career burnout. These risks exist for a variety of reasons tied to longstanding issues in the field, such as mental health stigmatization, lack of supportive services or resources, as well as “warrior” or “protector” cultural mindsets that put patient care over self-care. The work itself may require these individuals to consistently be exposed to—and interact with—illness, injury, and human misfortune.

An October 2019 National Academy of Medicine report found, “As many as half of the country’s doctors and nurses experience substantial symptoms of burnout.” This can result in increased risks to patients and has classically led to: malpractice claims, worker turnover, mental distress, trauma disorders, depression, anxiety, interfamilial issues, social isolation, and detachment, as well as billions of dollars in losses to the medical industry each year. Dedication to caregiving can backfire dangerously when these passionate personnel are placed within environments that don’t have built-in mental health supports and resources.

Even though this issue has been widely studied, COVID-19 has compounded the risk factors for those dedicated to caring for us. Without supporting these members with more intention, they will continue to be “canaries in the coal mine” for longstanding provider well-being public health inadequacies.

The risk is clear. US military personnel who were inserted into New York City hospitals to assist clinical care and hospital capacity observed, “This is the closest to combat that we’ve seen in a civilian setting.”

Family members of healthcare personnel who passed away from COVID-19 in Illinois noted the parallels with 9/11 rescuers. Their loved ones did not pause in their work, even while reusing their gloves, masks, and protective gowns. This can create working environments that increase fatigue and medical mistakes, as well as raise the risk of contracting COVID-19 themselves or infecting their families.

Previous pandemics provide another window into these risks. A recent Annals of Internal Medicine literature review found high levels (75 percent) of psychiatric morbidity rates among healthcare workers who experienced previous pandemics such as SARS, H1N1, and Ebola. Environments that mix high levels of anxiety with prolonged uncertainty and minimal professional control put these individuals at unique risk for developing persistent health issues, such as PTSD, sleep disorders, and depression, well after experiencing the pandemic.

Bearing Witness to the Suffering

COVID-19 has exposed workers to entirely new issues that affect their mental, emotional, and physical well-being. Rapidly deteriorating patients, uncertainty about COVID-19 itself, and the tragic uptick of patients dying alone are just a few. The increased exposure to human suffering compounded with the economic crisis and racial injustices and violence, has destabilized prior roles, responsibilities, and procedures for healthcare workers.

“It’s just witnessing the worsening of human suffering overall, both in terms of resources that people need. People’s food security, places to get food or shelter for folks, any financial situation—that was really, really tenuous for a lot of the patients that I take care of, and has essentially fallen apart,” says Surlyn, highlighting the multipronged issues to which workers are exposed. “Bearing witness to that firsthand and having people tell you about their experiences and their anxieties and how hard everything is…you sort of need to absorb that. You’re the cushion for it.”

The pandemic has exacerbated longstanding issues affecting healthcare workers as well as the communities they serve, which exposes these professionals to higher amounts of trauma and patients in distress. Personnel may be over-encumbered by time-consuming PPE procedures, under-resourced and stressed from taking on new roles, with further anxiety connected to the uncertainty of COVID-19, unclear messaging, and national politicization of the pandemic.

This only causes more concern for professionals like Surlyn, who sees an upside-down world where no one seems to be steering the ship, leaving an environment prone for questioning scientists, spreading rumors, and fake perceptions. “Especially when you bear witness to how real it is, and how insanely damaging it is. It’s just really frustrating and maddening to just hear people deny the reality that you know exists,” she says.

It is clear that the politicization of this pandemic and outright denial of its human toll is requiring health systems and personnel to create their own support systems. Yet, this comes at the cost of the time, energy, and the emotional bandwidth of the caretaking community. While the profession was lauded as “heroes of the frontline,” many national leaders are already treating COVID-19 as on its way out. Research and best practices in the field highlight the importance of leadership fostering a supportive, clear, and community-focused culture.

Normalizing Support and Creating Community

COVID-19 has required rapid development of innovative measures in medicine, deployment of personnel, and national public health discussion. That same energy must be directed at the well-being of healthcare workers.

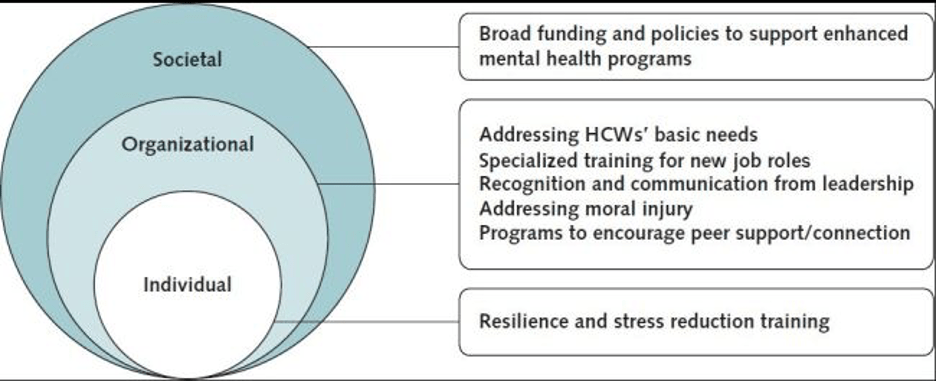

A multidisciplinary systems level approach may be most effective to meet the needs of healthcare workers because their situation involves complex longstanding and widespread issues. A systems approach centers on how the social-emotional and professional needs of personnel can be bettered by focusing across levels such as policy, workplace culture, training, leadership communication, and access to resources, services, self-care tools, community spaces, and more.

This is not to say that many health organizations have not committed resources towards staff well-being, but these needs are ever-changing. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends opening lines of communication with leadership, maintaining appropriate staffing levels, as well as insurance coverage and fair wage policy assistance befitting the mental health needs of healthcare personnel.

The Annals of Internal Medicine report found seven interconnected areas of focus that can benefit healthcare worker well-being. These fall into three main categories of intervention: individual (emotional support, self-care skills); organizational (leadership engagement, workplace cultures, resources and policies); and societal (destigmatizing mental health, normalizing caretaker support). The recommendations, along with how they have been utilized in the field, can be found below.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

1: The Need for Resilience and Stress Reduction Training

Incorporating an APD model (anticipate, plan, and deter) for stress reduction can assist healthcare professionals build adaptive capacity. This can take many forms, such as preventative training within health organizations, routine wellness check-ins, daily self-reflections, or simply providing access to supportive materials.

The Healthcare Association of New York State (HANYS), a health care advocacy nonprofit, has a plethora of supportive materials such as toolkits for emotional coping, leadership trainings on responding to staff stress, with accessible materials like self-care check lists, free mental health apps, and informative podcasts.

Helping healthcare workers understand and integrate self-care practices into their routines can not only strengthen their personal capacity but communicate across cultures the importance of these sustainable measures.

2: Providing for Clinicians’ Basic Needs

Essential to supporting healthcare personnel’s psychological well-being is making sure that basic needs like food, rest, shelter, transportation, childcare, financial security, and PPE are steadily met. Some health systems in urban environments where workers rely on public transit subsidized their transportation costs, even exploring the viability of bike or car rental options. Cities in the NY-NJ-CT tristate area aimed to provide childcare security by opening childcare centers and creating volunteer childcare programs specifically for children of healthcare workers.

As basic as these needs are, they impact the stress level for personnel who are already exposed to high levels of human suffering, tragedy, and trauma from COVID-19.

3: The Importance of Specialized Training for New Job Roles

For many healthcare professionals, having to deploy to a new role in the face of patient surges or vacancies was a major source of anxiety. Much of this can be mitigated by developing specialized skill trainings, such as infection control, and teaching personnel how to identify and respond to patients in psychological distress.

Incorporating specialized skills training programs focused around emergency redeployment can be beneficial to prepare for future periods of mass uncertainty and alleviate anxiety.

4: Recognition and Clear Communication from Leadership

Leadership communication can empower staff—or stir anxiety. The current volatile politicization from the highest levels of government can be a major anxiety-inducing stressor. Leadership within health systems has the important role of garnering trust, providing up-to-date information and reassurance while staff operates within the uncertainty of a pandemic. Along with clear communication, concrete action on the needs of personnel, consistent check-ins, and active listening can reflect a culture of support.

Acts as simple as weekly debriefs, one-on-one check-ins, and exuding transparency can be valuable for empowering staff morale. Leadership can also normalize the importance of mental health and self-care maintenance by investing funding toward supportive resources, as well as by creating organizational emergency mental health plans that can be activated during times of mass stress.

Normalizing the importance of self-care within an environment of mass trauma and uncertainty can be highly beneficial.

5: Acknowledgment of, and Strategies for, Addressing Moral Injury

Instances of moral injury are defined as psychological harm caused by the supposed betrayal of what one deems as “right,” when they are in a position of authority. There are multiple ways this can occur during COVID-19, from enforcing protective policies that force patients to die alone, deciding which patients receive life-sustaining resources, as well as communicating difficult news to staff members and families.

Some of the best measures to protect against instances of moral injury are increasing awareness of the symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and guilt. Leaders can also proactively monitor, understand, and support the well-being of staff, because in many cases those experiencing moral injury may be less apt to connect to services. Creating a culture of support and normalization that is professionally resourced may increase the likelihood individuals who are suffering will engage with services.

6: The Need for Peer and Social Support Interventions

COVID-19 has significantly inhibited regular social connection, which comes at a high psychological cost. Providing consistent opportunities for social connection can improve personal mental well-being. Personnel may be deprived of social interaction from their families, colleagues, and communities, which were classically available to meet psychological needs prior to COVID-19.

Institutions and organizational leadership can instill social support through direct programming, fostering peer discussion, and using “buddy” support systems. Some health systems copied a model used by the military with “battle buddies.” Staff members were partnered in a peer-support program and would engage in daily check-ins to look out for each other’s well-being, as well as undergo training to better understand indicators of distress within themselves and their partner. These steps highlight the importance of fostering a stigma-free conception of mental health needs. Some organizations even created multidisciplinary teams to focus on staffwide stress and anxiety.

St. Luke’s, a hospital in Boise, Idaho, has created a variety of programs, such as daily yoga and accessible counseling, as well as a critical incident stress management team to assist in particularly traumatic staff incidents or experiences. “[It’s used] to normalize those feelings of sometimes inadequacy or fears and being able to share that common experience of what happened in that situation,” Dr. Beth Gray of St. Luke’s, told Idaho News in regards to the team’s creation.

7: Normalization and Provision of Mental Health Support Programs

Researchers recommend creating awareness campaigns for the public, as well as a national epidemiological tracking program to focus on personnel well-being and the efficacy of interventions. Developing a culture of caring for patients and personnel normalizes asking for support, destigmatizes the manifestations of trauma, and provides staff with the resources, lessons, and support to care for others.

Conclusion: Caring for Care Workers

Widespread proactive national clinician support is needed to establish the resources, programming, and methods to care for those negatively affected by COVID-19. Federal funding, policy, and advocacy can help normalize and destigmatize healthcare personnel’s mental health needs. We must prioritize mental health care with understanding, empathy, and action.

A recent report from National Nurses United, the largest US union for registered nurses, found more than 1,700 workers have passed away. The union has also faulted the government for a failing to adequately track national healthcare fatalities due to COVID-19. These realities can be even harsher for workers who lack sufficient mental health support, trust in leadership, and workplace environments that value the importance of self-care and sustainability.

Effective leadership techniques, peer programming, and innovative resources are beneficial, but without national support and federal funding, many of these organizations and personnel will be operating in separate silos, putting themselves and patients at risk. It is highly impactful when leadership normalizes support and models self-care as peers foster help-seeking behaviors.

Author note: All quotes from Dr. Colleen Surlyn reflect her own views and not the San Francisco Health Network.