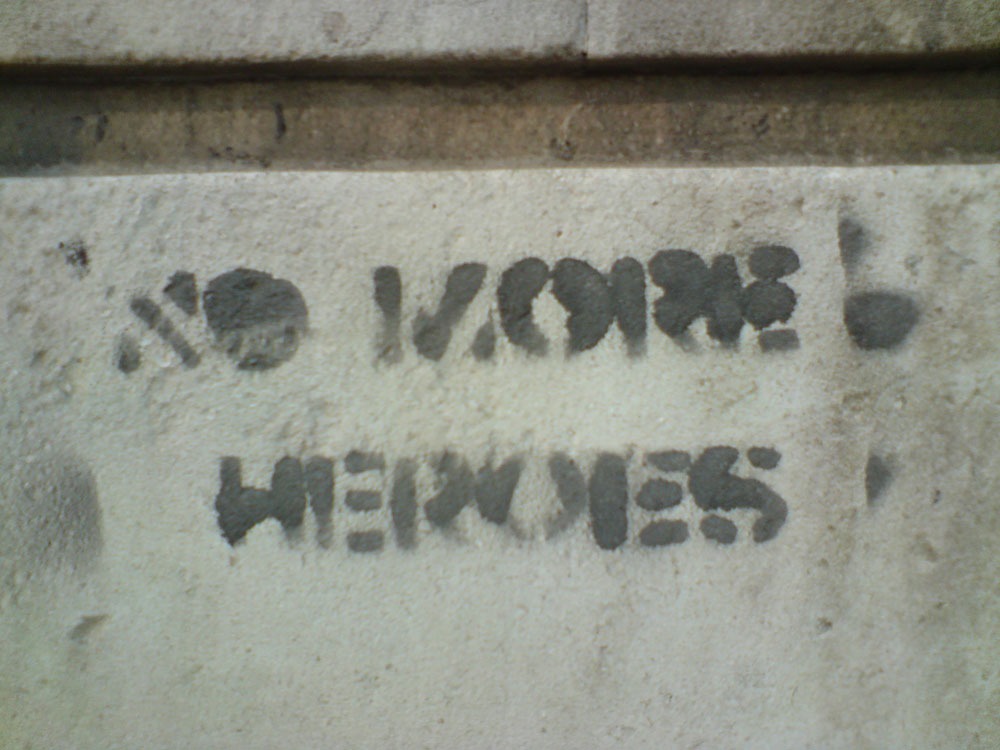

Nearly 50,000 healthcare personnel were infected with COVID-19 in February and March. Those who have survived are being hailed as “heroes” in the media. But some argue that calling frontline workers heroes ignores the systemic failures that continue to jeopardize their lives and well-being—failures we analyze in more detail in this accompanying article.

In our latest Tiny Spark podcast, we hear accounts from four frontline healthcare workers about the unsafe working conditions they have faced, their struggles with extreme anxiety and grief, and why they reject the “hero” label.

“I don’t feel like a hero,” Jane, a registered nurse, tells us, describing her utter frustration and anguish with the fact that she cannot save more lives. “We do have some good, positive outcomes. We do discharge people home, but it’s rare,” she says.

All four nurses we spoke to are immigrant women of color, just like many of those who work in the sector. By their request, we changed their names to protect their identities; all of them work in hospitals or nursing homes where there is COVID-19.

“We, as nurses, are supposed to make people better,” Lucy, another registered nurse, tells us. “We are supposed to provide support and healing. But when it comes to a situation like this, where you’re losing one or two or three a day, it’s very devastating. We are working tirelessly. We are trying so hard. It is a situation like I’ve never seen before.”

All four nurses say they lack adequate personal protective equipment, which jeopardizes not only their health, but the health of their colleagues, their families, and their patients. A vital form of protection for these frontline workers are N-95 respirator masks, which filter ninety-five percent of airborne particles, but there are widespread shortages.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Working on a COVID floor, Jane says she is forced to wear the same N-95 mask for four shifts before her hospital will provide her with a new one. Prior to COVID, she would use them for a single patient encounter and would then dispose of it immediately. Jane estimates that now she takes her mask on and off up to 100 times over the course of four shifts.

“You’re working close to a patient, you’re listening to their lungs, you’re changing them, you’re toileting them, you’re doing wound care,” she explains. “So, you’re in very close contact with the patient who also has COVID. They’re coughing. Once you get out of that room, and you’re removing that mask and putting it in a brown paper bag and having to pick it up next time to put it on, there’s a very high chance that you will contaminate yourself. So, it’s unsafe,” she says.

We also hear about how unsupported these women feel by management at the institutions where they work and learn of the extreme pressure they face from supervisors to show up, even when they are unwell. They describe the anxiety and grief that comes with a job where death and infection is all around, and talk about the reasons why they persist, even though they are perpetually short-staffed and at risk.

“I don’t want to work 80 hours a week, but who’s going to take care of these people?” says Lucy, a supervisor at a nursing home that houses 160 residents. She’s been working some 80 hours a week at two facilities where residents have COVID. “The reason why I became a nurse is to take care of people.”

Despite the long hours, Lucy said she is still asked to do even more shifts. “I’m tired,” she says. “I need to refresh.”

As an immigrant working in America, Jane says she is shocked by the shortcomings and shortages that have led to so much death, anxiety, and risk for frontline healthcare workers. “In a nation like this, we should have been better prepared,” she says. “There were red flags since the winter but for some reason we waited until this blew up, so the system definitely failed the whole country,” she says. “Other countries are looking and thinking, ‘Oh, it’s America. You have all the equipment, you are [a] superpower, you should be good with this.’ But we’re not.”

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

- Karen Yourish, K.K. Rebecca Lai, Danielle Ivory, and Mitch Smith, “One-Third of All U.S. Coronavirus Deaths Are Nursing Home Residents or Workers, New York Times, May 11, 2020.

- Szilvia Altorjai and Jeanne Batalova, “Immigrant Health-Care Workers in the United States,” Migration Policy Institute, June 28, 2017.

- Zaria Gorvett, “Can you kill coronavirus with UV light?” BBC, April 24, 2020.

- “Support Nurses and Midwives through COVID-19 and beyond,” World Health Organization, April 7, 2020.

- Amy Costello, “Nonprofit Wage Ghettos: An Intimate Profile of the Home Healthcare Workforce,” NPQ, October 2, 2018.

Photo Credit: “No More Heroes,” By Euston Square station, south side. Credit: MisterSnappy.