July 30, 2020; National Education Resource Center

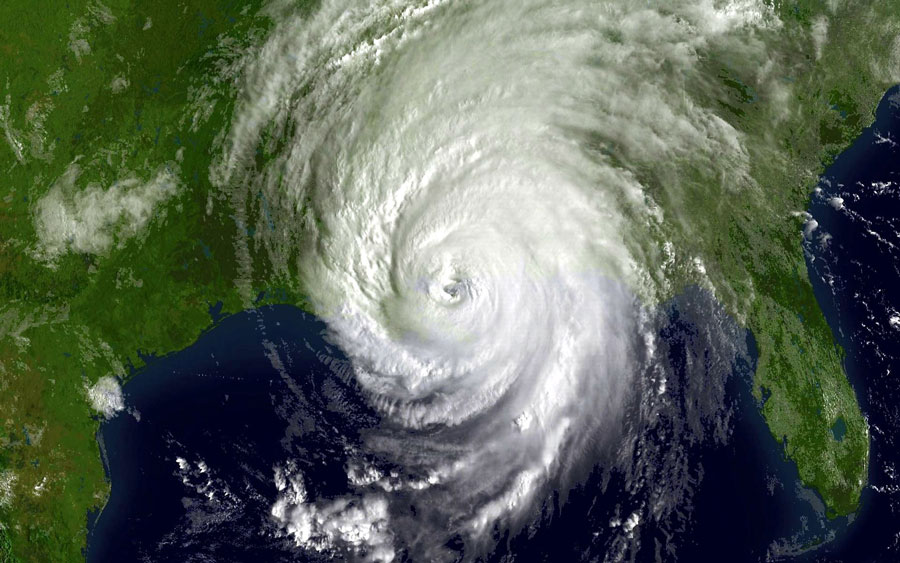

Hurricane season, one predicted to be severe, has begun. In “normal” times. we know the havoc a storm can cause. With a pandemic ravaging our nation, hurricanes add just one more thing to worry about. But that is not to say we cannot learn from these storms: indeed, they have important lessons to teach us about racial inequity and how to avoid repeating past errors.

As communities shift to face storm clouds, in a recent paper published by the National Education Research Center, Kristen Buras of Georgia State University warns that as we prepare we urgently need to learn from our past.

Using Hurricane Katrina as a model, Buras suggests that nearly every natural disaster impacts communities of color the hardest and that recovery efforts leave them further behind. From her study, Buras shows how systemic racism is built into public policies.

We have of course, seen the same in the pandemic’s health and economic impacts. Buras points out that even how we see those numbers reflects our inability to recognize the inherent inequity of our nation.

As Buras observes, “those statistics are portrayed as a radical deviation from the norm.” But the larger question is why we as a nation do not express similar dismay when unemployment rates even higher than those experienced during COVID-19 are regularly experienced by Black communities in New Orleans and other cities.

Buras notes that, “the capacity to tolerate an unemployment rate exceeding 50 percent under “normal” conditions—so long as it only affects African Americans—speaks wholeheartedly to tolerance for racism.”

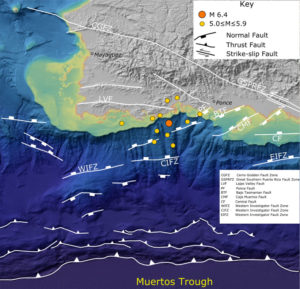

Buras reminds us too that the fact that Black and Brown neighborhoods were more vulnerable was not a surprise. As she details, “In 2001, journalist Mark Fischetti reported: New Orleans is a disaster waiting to happen…If a big, slow-moving hurricane crossed the Gulf of Mexico on the right track, it would drive a sea surge that would drown New Orleans under 20 feet of water…Scientists at Louisiana State University (LSU) who have modeled hundreds of possible storm tracks on advanced computers predict that more than 100,000 people could die.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The impact on Black and Brown communities were a direct result of earlier decisions by city officials to place their neighborhoods in locations most at risk of flooding. When the storm neared, public officials did not consider the differential rates of private car ownership that left Black residents stranded in the rising flood waters. Even the lack of urgency in the rescue efforts when the waters receded left thousands stranded demonstrating that to many in authority Black lives did not matter.

A similar pattern is reflected today in data today that show COVID-19 is not color blind and that the systemic inequities that have shaped the jobs people have, where they live, the quality of their health care, the effectiveness of their schools, and how they interact with the justice system have left them more vulnerable to the virus.

Death rates suffered by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color are higher than for whites. The economic burdens are greater on these communities as businesses shrink and jobs are lost. Even simple self-care actions like working from home and practicing social isolation are far more difficult in these communities. And, as was true with the Katrina death toll in New Orleans, more people of color have died from the virus. The health economic impact of the virus is amplified by the underlying racial disparity in income and wealth that has been well known but not addressed.

As Buras details, “the politics of race would powerfully influence the city’s rebuilding.” She notes in a 2005 Wall Street Journal article, James Reiss, who was then chair of New Orleans Business Council, remarked, “Those who want to see this city rebuilt want to see it done in a completely different way: demographically, politically, and economically.” After the storm passed, housing in affluent white neighborhoods of New Orleans was rebuilt quickly, while the hardest hit areas of historic Black neighborhoods often remained empty.

Priority was given to investing in efforts to restore businesses in the center city and not in the neighborhoods. Black, Brown, and low-income communities were not well represented in the rooms where critical decisions were made about where and how a devastated city should be rebuilt.

Buras emphasizes that just as the “struggle over who would have a voice in rebuilding New Orleans underscores the role of racial and economic power in infrastructure decisions,” we may expect a similar struggle with COVID-19. As Buras puts it, “Like Katrina, the economic shutdown resulting from COVID-19 will alter neighborhood landscapes. Many local businesses may be unable to reopen. If the unemployed cannot pay their bills, they may be evicted, leaving residential properties vacant. The end of post-Katrina rent help was devastating for many. State and local budgets will be tighter…Austerity and unequal power can be a lethal combination when it comes to who exactly will determine the use of limited resources.”

As cities, states, and the federal government debate how much will be allocated to protect businesses and individuals from COVID-19, the lessons of Katrina ring loudly. If we can recognize that race has created conditions which determine how a storm, or a disease, will harm people differently, we must examine where and how we invest with a powerful equity and reparations lens in use.— Martin Levine