Editors’ note: This article is featured in NPQ’s new, winter 2014 edition, “Births and Deaths in the Nonprofit Sector.”

Nonprofit-based journalism sites are by no means new. There are some that have been around for decades—Mother Jones, The Nation, and even the Associated Press, for instance—but there is a new crop of sites that have emerged over the last seven years from the detritus of the implosion of the old landscape of journalism.

Among the refugees of that implosion were many serious journalists committed to the delivery of high-quality news. These are the people—passionate and tenacious devotees of the civic purpose of the profession—who started many of the new sites.

This makes them classic nonprofit founders: mission focused, and not necessarily focused on infrastructure development. This focus on mission, by the way, is a wonderful and necessary thing, establishing the DNA or “imprint” of the organization; but, except in a few cases, the purpose fire in the belly of the organization, while critical to igniting the effort and giving it life, is not necessarily sufficient to sustain it over the long term.

Over time, someone has to attend to what kinds of revenue can be raised and managed with what kinds of capital and effort, how to treat staff fairly and get the most from them, and how to develop reasonable decision-making models. Conflict and failure around these issues typically plague organizations under seven years old, although this not a strict rule. For some organizations, these so-called “first-stage” issues can extend even further out, treating participants to decades of arbitrary, unstable, and quirky practices that somehow survive on such stuff as the strength of the involved community. For most new organizations, however, there is a wall one runs into sooner rather than later, and sometimes in ways that are incredibly painful and embarrassing, letting the organization know that inaction—as well as action—in some realms has consequences.

Nonprofit Patterns of Early Development

The idea that all organizations typically go through so-called stages of development was first deeply discussed in an article by Larry Greiner, “Evolution and Revolution as Organizations Grow,” originally published in the Harvard Business Review in 1972, and then updated in 1998.1

As outlined by Greiner, the characteristic of the first phase is a period of creative evolution, defined by the following:

- The company’s founders are usually technically or entrepreneurially oriented, and they disdain management activities; their physical and mental energies are absorbed entirely in making and selling a new product.

- Communication among employees is frequent and informal.

- Long hours of work are rewarded by modest salaries and the promise of ownership benefits.

- Control of activities comes from immediate marketplace feedback: the management acts as the customers react.2

“All of the foregoing individualistic and creative activities are essential for the company to get off the ground,” writes Greiner. “But therein lies the problem. As the company grows, larger production runs require knowledge about the efficiencies of manufacturing. Increased numbers of employees cannot be managed exclusively through informal communication; new employees are not motivated by an intense dedication to the product or organization. Additional capital must be secured, and new accounting procedures are needed for financial control.”3

This realm of literature simply tries to discern the patterns that many organizations exhibit as they start up, mature, and reorganize or die. Patterns, when they are accurate, are incredibly valuable as signposts, but there are plenty of exceptions, particularly as some organizations, such as digitally based ones, are taking on new forms.

At the heart of Greiner’s research is the idea that organizations often have to face potential failure before they are motivated to change significantly. This failure can take many forms in nonprofits—informality coupled with leaders’ heavy-handedness may dull the development of the staff or cause revolts and loss of key staff, and finances may be mismanaged or systems in general may not match the expectations of funders. And undergirding all this may be the assumption that the quality of the core work will save the endeavor. In fact, in the end, the informality of many organizations in this startup stage may cause failures in the program that call even the quality of the product into question.

These are the kinds of problems—and they are sometimes made very public—that spark attempts to change the way the organization functions.

The Buffering Effect of Infrastructure

Again, there are mediating factors that can make transitions from less-attentive administrative and revenue-producing systems to more-attentive systems potentially less painful. One of these factors is the presence of a funding source or infrastructure (or both) that is attempting to push the field toward a sustainable state. In the field of nonprofit journalism, there are the Knight Foundation and the Investigative News Network.

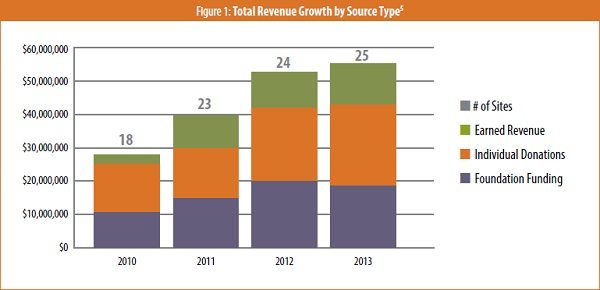

These organizations provide not only support but valuable information that is like parenting guidelines for children’s developmental stages. For instance, having the information contained in figures 1 through 4, drawn from an upcoming report on nonprofit news sites by the Knight Foundation, gives these new organizations benchmarks that are not keyed to an idea but rather to reality.4

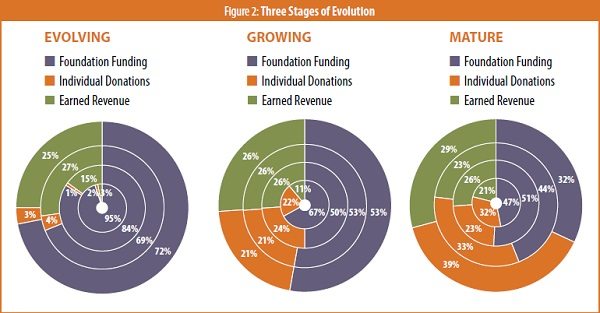

Figure 1 demonstrates the pattern of the changes in revenue mix in the first few years of life. These patterns are, of course, not a rule but rather an indicator of how the mix changes in the first few years. But organizations mature at different rates within their early lives, and figure 2 exhibits three different stages of evolution tracked through revenue mix.

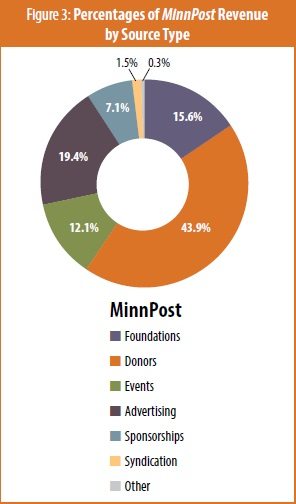

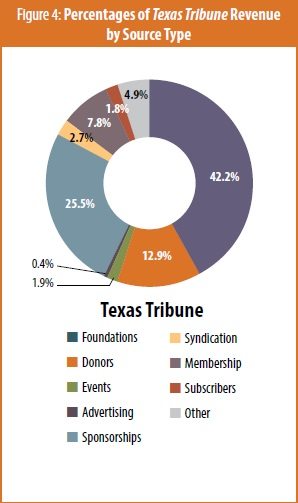

An important variable to be considered in all of this is that the business model in the whole field is both still in development and very sensitive to the specifics of the individual endeavor. As figure 3 shows, the seven-year-old MinnPost, which has a budget of $1.6 million, has a healthy proportion of its income flowing from donors. The well-capitalized, five-year-old Texas Tribune (figure 4), with a budget in excess of $7 million, however, looks very different: it is a creature of a hyperpolitical environment, and its engagement of its readers is designed around events that emphasize that brand and thus it is particularly strong on sponsorship income. The mix would show this even more clearly in the Texas Tribune figure if the amount of foundation funding in the year depicted (2013) were not an anomaly: $3 million, a figure approximately five times as large as the $600,000 in foundation support in each of the previous two years. From this we can assume that the events and sponsorship categories would normally account for an even larger percentage of the revenue pie than the combined 27.4 percent listed here. So we can see that the two organizations may not be in different stages of development so much as have different markets and business models, and this is reflected in the Knight report’s designation of both as “established,” as compared to “growing” or “mature.”

Thus, it is not possible to just pick up and fine-tune tested strategies for revenue and audience development. In the last ten years, even some of the most well-capitalized and most heralded experiments in revenue models for journalism have failed—many of them in for-profit environments (think paywalls). Nonprofit news sites must understand the conditions in which a particular strategy has succeeded or failed; then, each organization must build the infrastructure to run its own experiments, which are like mini-negotiations with stakeholders—and potential stakeholders—about the specific product offered. This is a very sophisticated endeavor for an enterprise not necessarily oriented to business.

To address some of these systemic issues, the Investigative News Network (INN), which provides services to nonprofit news sites (including business training, technological help, and better rates for liability insurance), has established an innovation fund (among other supports) that provides small grants to nonprofit news sites for experimentation by individual groups in the areas of audience development, engagement, and revenue generation. The project includes requirements for measuring results and sharing the information with the field. The Knight Foundation, on its end, is attempting to acknowledge the variations in the field by sorting the twentyfive organizations it is studying into categories that would not necessarily have been understood to have been important in driving the organizations’ business models before they were identified as such in practice. This type of pattern recognition, which can only be done by looking at what’s going on from a balcony of sorts, is valuable beyond rubies.

In light of developmental pattern theory, the field of nonprofit news sites that the Knight Foundation has been studying is not in bad shape, but it is still classically a field of first-stage groups. “Within the first three years of an organization’s starting, we may see some spectacular crashes and burns,” says Marie Gilot, the Knight Foundation’s program officer for journalism. “But, with those surviving three years and going into five or more, we see that even though they may not have a very stable financial base, and even though they are still fragile, they have survived and are finding ways to sustain themselves for the time being. And, those that have survived have been the ones willing to experiment with a different revenue mix appropriate for their location.”6

Infrastructure Meets Individual Group Capacity and Focus

Still, each experiment that these groups run needs capacity. Specific expertise—advertising, sponsorships, donor development, and event management—requires up-front capital for what is, in the end, a speculative revenue program in that specific market. According to INN’s CEO and executive director Kevin Davis, all these systems and strategies need to be integrated into a comprehensive enterprise model: “There are three parallel strategies that need alignment. The content strategy needs to be aligned with an audience/community strategy, and those strategies need to be aligned with the revenue strategy.” This may not be easy for an undercapitalized organization led by a journalist with little business experience, but INN tries to help by offering an executive training program for community journalists. Davis says that undercapitalization and an overdependence on foundation money can be a deadly combination when time and capacity for experimentation are needed.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

There are also needs with regard to the marrying of content to technological delivery systems and the development and redevelopment of those systems—for instance, many organizations invested (sometimes a great deal) in apps that would make their content responsive to specific mobile devices, but these were soon superseded by methods that make content responsive to all devices. Additionally, organizations need staff who will systematically run all of these experiments, giving them enough rope to prove themselves but cutting them when they prove not to be ideal for the particular site. This investment of capital without a clear immediate payoff may be a tough sell for many foundations, although it is surely in the DNA of any entrepreneurial endeavor.

Gilot explains that the need or tendency to focus so intently on mission early on is hard to counteract, and that attempts to do so may in fact sometimes have a more complicated effect. As she describes it:

The best-case scenario is what happened with the Texas Tribune. They had an early, very big investor, who acted a little bit like a venture capitalist, or angel funder. And that person was very knowledgeable about growth and what it takes to build a business, even a nonprofit one, and insisted on some things, and that helped. But this is an exception. I think this problem of overinvesting on the editorial side is endemic across the board, including when these organizations had starter money from the Knight Foundation, for instance, or from large foundations. They often got a two-year grant to get started. But instead of pushing the Texas Tribune to diversify the funding and invest in the business side, the grant seemed to slow down that side. They focused on building the editorial side with their start-up money, and two years later they really started to hurt, because then the funding was phasing out. And they haven’t built anything to replace it.

Gilot does not downplay the difficulty in replacing that money, saying, “If you do investigative reporting, especially in a small city, it’s going to be hard to find businesses that are going to want to support that. This is why you don’t see a whole lot of sponsors on the websites like ProPublica that regularly uncover all sorts of corruption and mismanagement of large businesses or government contractors. That’s one of the reasons why we’re funding the Investigative News Network, which is a group that supports those smaller outfits.”

Every Group Has Its Own Issues to Work Out

Jonathan Sotsky, director of strategy and assessment at the Knight Foundation, is quick to point out that the fit of the news site to the environment creates idiosyncrasies that have to be built on and resolved:

We are looking for the things that can be replicated. So, when we see different sites experimenting with membership models and figuring out how to recast what would be considered something like just being a donor to something more like a model where donors receive certain benefits—whether it’s access to certain reporting, access to some events, or acknowledgment of some kind—we start to see the effectiveness of some of these strategies in one or two places and think that maybe there are opportunities to expand that model elsewhere. But some of the conditions that come with the success of certain sites or programs can be idiosyncratic.

Finding the right mix for the specific outlet is no one-size-fits-all endeavor, adds Gilot. Some have tried events, some are concentrating on sponsorships or donations, and others are offering their services for training—for example, a local university is paying the New England Center for Investigative Reporting to train journalism students.

Some are clearly very specifically tied to place and type. “In the case of the Texas Tribune,” says Gilot, “Texas is a rich state that happens to be completely consumed by Texas politics and has a very interested, very committed readership because of the whole Texas politics angle.” But, she adds, “understanding your audience is the key to making money online”:

So, for instance, the MinnPost in Minnesota invested some money in really understanding who their readership was, who was reading MinnPost online, and they found out that it tended to be people who are educated—young professional couples who are educated—and then people with disposable income. So they were able to sell that knowledge to the advertisers or sponsors—I don’t know if you can call them advertisers when it’s for a nonprofit, but to people who wanted to sponsor their website—by saying, “This is a highly valuable target audience that you’re reaching, thanks to us.” And, they are able to command a higher price for their advertising rates thanks to that particular knowledge. So, knowing your audience, knowing what it needs, fulfilling that need, and then, in turn, being able to show the people you want to ask for money that you know what you’re doing and that you’re answering a need for your target audience is really important.

But interacting with and really knowing that audience online is another stretch for many of the leaders of these young organizations:

Some early mistakes that occur with our journalists come from the fact that they don’t have a lot of knowledge about business. These are also journalists who, often, have worked in print or in a newsroom that had a website, but a destination website—and it takes a while for them to realize that they cannot expect people to come to their new website, which is unknown and doesn’t yet have brand recognition, and that they have to use social media to its full extent in order to reach out to people. So, they have to make an effort. People are not going to come to them—the publisher has to find the audience on social media (and elsewhere) and must work at growing their audience there, even though at first the site is not going to be making money. And it has taken a while for many of them to understand this. I think people are wiser now, but it took a while to realize that this entails a completely different relationship with your audience.

Metrics and Self-Awareness of Purpose

Although young, the field of nonprofit journalism is taking on some powerful societal and business innovation challenges that may keep it close to purpose, even while its systems develop; these challenges are all bound up with advances in technology.

Technology platforms, for instance, can produce massive amounts of data about readers—but, as with any data, there are a lot of paths to nowhere. Thus, the questions nonprofit news sites ask themselves about what to measure and how to interpret impact need to be very well thought through. This kind of activity is an advanced placement course in connecting purpose to program outcomes. Sotsky says that the maturing of the nonprofit news sites can be seen, in part, in their willingness to measure their impact and the sophistication with which they approach that element of the work:

Some sites are investing in software and systems to help track the impact of their reporting that go beyond just “here’s how many visitors we had on our site, and here’s the average onsite duration time.” I think that’s where the industry has been stalled in terms of measurement—those typical vanity metrics. And these sites are starting to move beyond the “who’s looking at our stuff?” questions to start to see what type of user engagement they have with their readers and whether their coverage is leading to policy changes or real-world impact.

• • •

These new organizations have to find their way together and separately—learning and teaching and challenging each other even while they are developing and solidifying their own characters in the form of principles, values, practices, and ways of interacting with the world. A knowledge scaffolding during such a time that patiently allows learning to emerge rather than imposing a logical but disconnected set of prescriptions on participants is unusual in this logic-model-driven philanthropic atmosphere, but a great model for other funders.

It is worth saying that adequate capitalization is equally important, especially if the availability of that capital depends on active experimentation with the enterprise model and open sharing of results. That said, given the central importance of independent journalism to civil society, the breaking down of traditional investigative journalism, the relatively good prospects for finding a revenue model that works for editorial independence, and the quality of current infrastructure, it would seem that nonprofit journalism should be much higher on this country’s list of innovative/entrepreneurial philanthropic priorities than it currently is.

Notes

- Larry E. Greiner, “Evolution and Revolution as Organizations Grow,” Harvard Business Review, July-August 1972, reprinted and updated May 1998, hbr.org/1998/05/evolution-and-revolution-as-organizations-grow.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The report, due to be published by the Knight Foundation in January 2015, examines the progress and challenges of the nonprofit news field through the lens of twenty-five nonprofit news organizations on the path to sustainability.

- All figures in this article are from the Knight Foundation’s upcoming report (see previous note).

- This and all subsequent quotes by Gilot, Kevin Davis, and Jon Sotsky are from interviews with the author.

Ruth McCambridge is the Nonprofit Quarterly’s editor in chief.